Adina Emilia de Zavala facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Adina Emilia De Zavala

|

|

|---|---|

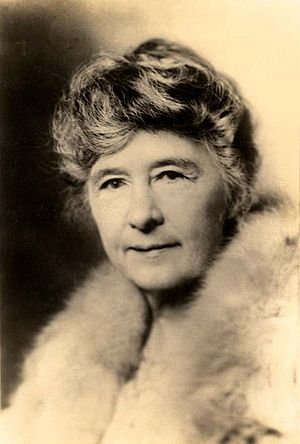

Adina De Zavala, c. 1910

|

|

| Born | November 28, 1861 |

| Died | March 1, 1955 (aged 93) |

| Occupation | Teacher Historian Preservationist |

| Known for | Saving the Alamo Long Barrack Fortress |

Adina Emilia De Zavala (born November 28, 1861 – died March 1, 1955) was an American teacher, historian, and someone who worked hard to save important historical places in Texas. She is best known for her efforts to protect the Alamo Long Barrack Fortress for everyone to see in the future.

Adina's father, Augustine De Zavala, was the son of Lorenzo de Zavala. Lorenzo was the very first Vice President of the Republic of Texas. Adina's mother, Julia Tyrrell De Zavala, was born in Ireland. Adina De Zavala has been honored with special markers. In 1994, a Recorded Texas Historic Landmark marker was placed at Alamo Plaza. Another marker was placed in St. Mary's Cemetery in 2008 to remember her contributions to Texas history.

Contents

Adina De Zavala: Texas History Hero

Early Life and Education

Adina's father, Augustine De Zavala, was a farmer. He joined the Confederate States Navy during the American Civil War. Adina grew up in a family with different backgrounds. Her mother was from Ireland, and her father's family was from Texas. Even though her family had a Spanish background, Adina never learned to speak Spanish.

Adina was taught at home until 1871. Then, she went to Ursuline Academy in Galveston. From 1879 to 1881, she studied at Sam Houston Normal Institute. This school is now called Sam Houston State University in Huntsville, Texas. She also studied music in Chillicothe, Missouri.

Adina became a teacher in Terrell, Texas from 1884 to 1886. In 1887, she moved to San Antonio to be with her family. There, she taught in elementary schools until 1907. She always made sure to teach her students about the history and heritage of Texas.

A Passion for Texas History

Adina De Zavala was a dedicated writer about Texas history. In 1900, she wrote a short play called The Six National Flags That Have Floated Over Texas. She created this play to teach people about the many different cultures in the state.

In 1917, she wrote History and Legends of the Alamo and Other Missions In and Around San Antonio. This book shared stories about the Alamo and Texas history. It also highlighted the important roles of women and other groups. Adina's 1916 book, Legend of the First Christmas at the Alamo (The Margil Vine), told a story about Franciscan friars and local Native Americans. It described them celebrating the birth of Jesus Christ in 1718.

In 1934, Adina wrote an article for the San Antonio Express. It was called In My Grandmother's Old Garden Where the Rose Reigned as Queen. In this article, she remembered the beautiful flowers in her grandmother's garden. She encouraged readers to plant roses for the 1936 Texas centennial celebration.

Adina gave most of her large collection of historical documents to the University of Texas at Austin in 1951. Today, scholars use these papers at The Dolph Briscoe Center for American History. The rest of her papers were given to the University of the Incarnate Word in San Antonio.

Working to Save History

Adina De Zavala strongly supported making March 2 a statewide holiday for Texas Independence Day. She also helped make sure that Texas public schools were named after state heroes. She was part of the executive council of the Texas State Historical Association. In 1945, she was made an honorary life member of the council.

Adina inspired her friend Anna Ellis, who helped start the San Antonio Conservation Society. Anna Ellis worked to restore homes that represented the six governments that had ruled Texas. These were Spain, France, Mexico, the Republic of Texas, the United States, and the Confederate States of America. Adina worked with Anna Ellis and others to save the Spanish Governor's Palace. They also saved other buildings, including homes of José Antonio Navarro, who signed the Texas Declaration of Independence. On March 2, 1951, the San Antonio Conservation Society gave Adina an award. It was for "marking historic homes and sites."

In 1887, Adina started an organization called the "De Zavala Daughters." This group was dedicated to preserving and marking Texas history. In 1893, the group changed its name. It became a chapter of the Daughters of the Republic of Texas (DRT). One of their first markers in 1897 was placed over the grave of Ben Milam. He died in 1835 while leading volunteers against Mexican troops.

In 1900, the De Zavala chapter created an Auxiliary. This was for people who could not join the main DRT group. In 1910, the Auxiliary became its own independent organization. It had chapters in several Texas towns. Between 1922 and 1935, this group researched and marked 28 historic sites in San Antonio. They also marked 10 other sites across the state. The organization stopped when Adina De Zavala died in 1955.

The Fight to Save the Alamo

By the late 1880s, the old San Antonio missions were falling apart. They were also being damaged by vandals. Adina De Zavala first focused on saving these historic buildings. She was especially interested in the Mission San Antonio de Valero, also known as the Alamo.

The main entrance to the Alamo, the mission chapel, was already owned by the State of Texas. The state bought it from the Roman Catholic Church in 1883. They gave the city of San Antonio care of the building. However, the city did not make any improvements. The state's ownership also did not include the long barracks building. This building was owned by a grocer named Gustav Schmeltzer.

Adina and her group convinced Gustav Schmeltzer to give them the first chance to buy the long barracks if it went up for sale. In 1903, she learned that the owners might sell it to a hotel company. Adina asked Clara Driscoll, a wealthy supporter of historical preservation, for money to buy the building. On January 26, 1905, Governor S.W.T Lanham signed a law for state money to save the Alamo property. The state paid back Clara Driscoll. On October 4, 1905, the governor officially gave the Alamo property to the Daughters of the Republic of Texas. This included both the long barracks and the mission church.

A disagreement started among members of the DRT and the public. They argued about how the long barracks should be used. Clara Driscoll and others thought it was not part of the original Alamo structure. They believed it should be turned into a park. But Adina was sure that the long barracks was where a major part of the historic battle had happened. To prove her point, Adina interviewed many families and friends of the men who died at the Alamo. In 1906, she got a sworn statement from Juan E. Barrera. He was born in San Antonio in 1839. He stated that the long barracks "are still standing just as they were when I was a boy."

The building's lease was ending on February 10, 1908. There were rumors that the property might be rented to a theater company. Two days before the lease ended, Adina hired three guards for the property. She also had a telephone installed in the old warehouse. New locks were put on the doors.

On the evening of February 10, 1908, Sheriff John W. Tobin arrived with his deputies. He had a court order stopping Adina from interfering. The guards were given the order and removed from the property. Adina refused to leave. She locked herself in an upstairs area without any food or supplies. The sheriff cut off the electricity and telephone. He also threatened to arrest anyone who brought her food. However, people managed to sneak in food and extra clothes. Law enforcement did allow water and coffee. Sheriff Tobin eventually turned the electricity back on for lights to keep rats away. Adina, who was 46 years old, said she was willing to die for her cause.

The standoff lasted three days. It attracted many spectators and was covered by newspapers across the country. Adina finally came out after her lawyers worked out an agreement. The agreement was to temporarily give the building to the governor.

By 1911, Governor Oscar Branch Colquitt ordered the long barracks to be restored. He wanted it to look like it did during the mission days. During the restoration in 1912, workers found old foundations. These discoveries proved that Adina was right. The structure had indeed been an original part of the Alamo. However, when Governor Colquitt left the state in 1913, Adina's efforts were partly undone. The Lieutenant Governor, William Harding Mayes, allowed the upper walls of the long barracks to be torn down.

Legacy and Recognition

Adina De Zavala passed away at the age of 93 on March 1, 1955. Her funeral was held on March 5 at St. Joseph Church in San Antonio. Her casket was covered with the flag of Texas. As a tribute, she was carried past the Alamo one last time. Adina is buried in her family's plot in St. Mary's Cemetery. She never married. She left her property to the Sisters of Charity of the Incarnate Word. She wanted them to start a vocational school for girls and a boys' town.

On April 27, 1955, the Texas State Legislature passed a resolution honoring her. It praised her for playing "a major role in preserving the Alamo and the Spanish Governor's Palace." It also noted her work in placing "permanent markers on some 40 historic sites in Texas."

In 1994, the Daughters of the Republic of Texas placed a special marker at her gravesite. The DRT Alamo Committee also placed a bronze marker in the Alamo. This marker honors both Adina De Zavala and Clara Driscoll. The Bexar County Historical Commission placed a State Historical Marker in Alamo Plaza to honor De Zavala.

See Also

- The Alamo

- Daughters of the Republic of Texas

- San Antonio Conservation Society

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |