Adriaen van der Donck facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Adriaen van der Donck

|

|

|---|---|

Possible portrait

|

|

| Born |

Adriaen Cornelissen van der Donck

c.1618 |

| Died | 1655 or 1656 |

| Alma mater | Leiden University |

| Signature | |

Adriaen Cornelissen van der Donck (around 1618–1655) was an important lawyer and landowner in New Netherland. The city of Yonkers, New York, is named after his special title, Jonkheer. While he wasn't the very first lawyer in the Dutch colony, Van der Donck was a key leader in the political life of New Amsterdam (which is now New York City). He worked hard to bring a Dutch-style republican government to the colony, which was run by the Dutch West India Company.

Van der Donck loved his new home in New Netherland. He wrote detailed notes about the land, plants, animals, rivers, and weather. He used this information to encourage more people to move to the colony. He even published a famous book called Description of New Netherland. Experts say that if it had been written in English, it would be considered one of the most important books about early American colonial times.

Today, Van der Donck is also known for his respectful writings about Native American cultures. He learned the languages and observed the customs of the Mahicans and Mohawks. His descriptions are still used in many modern books about Native American history.

Contents

Early Life of Adriaen van der Donck

Adriaen van der Donck was born around 1618 in Breda, a town in the southern Netherlands. His family was well-known. His mother's father, Adriaen van Bergen, was a hero who helped free Breda from Spanish forces during the Eighty Years' War.

In 1638, Van der Donck began studying law at the University of Leiden. Leiden was a major center for learning because the Netherlands allowed religious freedom and didn't censor books. At Leiden, he earned a special law degree. Even though the Dutch economy was doing well, Van der Donck decided to move to the New World. He got a job as a schout (a mix of sheriff and prosecutor) for a large estate called Rensselaerswijck. This estate belonged to a wealthy landowner named Kiliaen van Rensselaer and was located near what is now Albany, New York.

Life in New Netherland

Working in Rensselaerswyck

| Rensselaerswyck series | |

|---|---|

| Dutch West India Company |

|

| The Patroon System |

|

| Map of Rensselaerswyck |

|

| Patroons of Rensselaerswyck: Kiliaen van Rensselaer |

|

In 1641, Van der Donck sailed to the New World on a ship called Den Eykenboom (The Oak Tree). He was amazed by the land, which was very different from the Netherlands. It was covered in thick forests, hills, and full of wild animals. Once he started his job, he quickly annoyed Van Rensselaer because he was very independent. For example, he chose one of the best horses for himself and picked a different farm site than the one he was given.

Van Rensselaer expected Van der Donck to focus on making money for the colony, not on the colonists' well-being. But Van der Donck often ignored orders. He refused to collect late rent from people who couldn't pay. He also argued that colonists couldn't make their servants swear loyalty oaths. Instead, he started improving mills and building a brickyard. Van Rensselaer became very frustrated, writing that Van der Donck acted "not as officer but as director."

Van der Donck also spent a lot of time exploring the area, which his employer didn't like. During these trips, he learned a great deal about the land and its people. He often neglected his official duties because he was so eager to observe and write down everything he saw. He met local Native Americans, like the Mahicans and Mohawks, ate their food, and became good at their languages. Van der Donck wrote detailed and fair descriptions of their customs, beliefs, medicine, and way of life.

Van der Donck wasn't happy in his job. He saw the great potential of the land and began using his connections with Native Americans to buy land in the Catskills. He wanted to start his own colony there. When Van Rensselaer found out, he quickly bought the land first. So, Van der Donck's contract as schout was not renewed in 1644.

Early Political Efforts

In New Amsterdam, many colonists were unhappy with the Director-General, Willem Kieft. Kieft had started a difficult war with the Native Americans, even though his advisors had told him not to. This conflict, known as Kieft's War, hurt trade and made life dangerous for colonists. Kieft also made colonists angry by taxing beaver furs and beer to pay for the war.

In 1645, Kieft tried to make peace with the Native Americans and asked Van der Donck to help as a guide and interpreter. During the peace talks, Kieft forgot to bring important gifts, which were needed for negotiations. Van der Donck hadn't told Kieft about this beforehand, but he happened to have enough sewant (wampum) and loaned it to Kieft.

In return for this favor, Kieft gave Van der Donck a large piece of land, about 24,000 acres, north of Manhattan in 1646. Van der Donck named his estate Colen Donck. He built several mills along a stream he called the Saeck Kill, which is now the Saw Mill. The estate was so big that locals called him the Jonkheer ("young gentleman" or "squire"). This word is where the name "Yonkers" comes from. Around this time, Van der Donck married Mary Doughty, whose father had lost his land after upsetting Kieft.

Kieft remained unpopular with the colonists. Adriaen van der Donck stepped into this troubled situation. He used his legal skills to speak for the unhappy colonists. When he arrived, the colonists' complaints suddenly became much stronger. While he seemed to be helping Kieft as a lawyer and translator, he was secretly working with others to get Kieft removed. He also wanted to convince the Dutch West India Company that New Amsterdam needed a representative government, like the one in the Netherlands.

The Dutch West India Company did decide to remove Kieft in 1645 because his war had badly damaged trade. However, instead of giving the colonists local government, the company chose a stronger Director-General, Peter Stuyvesant. Despite this change, Van der Donck kept writing documents against Kieft. He used Kieft's example to argue for the creation of a local government.

The Board of Nine

The new director-general, Peter Stuyvesant, tried to rule with a firm hand. People said that anyone who opposed Stuyvesant "hath as much as the sun and moon against him." But eventually, he had to agree to create a permanent advisory board. Following a Dutch tradition, eighteen people were elected, and Stuyvesant chose nine to serve. Van der Donck was one of the nine chosen in December 1648, and he quickly became a leading figure.

Van der Donck started writing down all the colonists' complaints against the West India Company, Kieft, and Stuyvesant. He planned to combine them into one document to present to the Dutch States General (the Dutch government). When Stuyvesant found out, he put Van der Donck under house arrest, took his papers, and removed him from the Board of Nine.

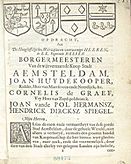

Despite this, on July 26, 1649, eleven members of the Nine Men (current and former) signed the Petition of the Commonality of New Netherland. This petition asked the States General to encourage economic freedom and create a local government like the one in the Netherlands. Van der Donck was one of three men chosen to travel to the Netherlands to present this request. They also brought a description of the colony, mostly written by Van der Donck, called Remonstrance of New Netherland. This document argued that the colony was very valuable but was in danger of being lost due to poor management by the Dutch West India Company.

Return to the Netherlands

While in the Netherlands, Van der Donck worked on political and public relations campaigns. He also helped organize groups of new colonists to move to New Netherland. He presented his case to the States General many times, arguing against a representative sent by Stuyvesant.

Promoting the Colony

The case before the States General was delayed because of problems within the Dutch government. During this delay, Van der Donck focused on public relations. In 1650, he printed his Remonstrance as a pamphlet. His exciting description of the land and its potential made many people eager to move to New Netherland. So many wanted to immigrate that ships had to turn away paying passengers. A director of the Dutch West India Company wrote, "Formerly New Netherland was never spoken of, and now heaven and earth seem to be stirred up by it."

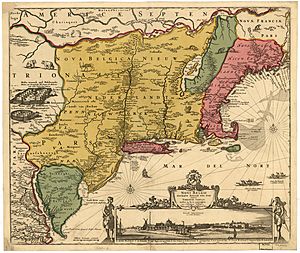

To go with the Remonstrance, Van der Donck ordered a map of the colony called the Jansson-Visscher map. The map was colorful and designed to look appealing. It showed New Netherland and included drawings of Native American villages, wild animals, and the town of New Amsterdam. This map remained the main map of the area for over a hundred years, helping to keep many Dutch place names. It was reprinted 31 times before the mid-1700s.

States General's Decision

Van der Donck's efforts to go public seemed to work. In April 1650, the States General ordered the West India Company to create a more open form of government to encourage people to move to the Dutch colony. Their final decision came in 1652: the Dutch West India Company had to tell Stuyvesant to set up a municipal government. A city charter was put in place in New Amsterdam on February 2, 1653. The States General also wrote a letter in April 1652 demanding that Stuyvesant return to the Netherlands, and Van der Donck was supposed to deliver this letter himself.

Van der Donck got ready to return to New Amsterdam. He had successfully gained a more open government for the colony, free from some of the Dutch West India Company's strict rules. He also had national support for colonists moving from the Netherlands. He was even put back as President of the Board of Nine and would be a leader in the new government.

But on May 29, 1652, before Van der Donck could sail home, the First Anglo-Dutch War broke out. His plans for New Amsterdam suddenly changed. The States General worried about trying new forms of government during a war. They needed the close help of the West India Company, which was almost like a military branch. So, they changed their decision.

Defeated, Van der Donck tried to return to New Netherland, but he was stopped because his activism had caused problems. Meanwhile, he earned another law degree at the University of Leiden. Still eager to promote the colony, he wrote a detailed book about its geography and native peoples. This new book was based on his earlier Remonstrance. It included an analysis of European claims to New Netherland, a long description of Native Americans and their customs, a chapter on beavers, and a conversation between a Dutch "Patriot" and a New Netherlander answering questions from potential colonists.

Even though it was finished in July 1653, the publication of Beschryvinge van Nieuw-Nederlant (Description of New Netherland) was delayed until 1655 because of the war. Van der Donck wanted to encourage more people to settle in the colony. The book was very popular and had a second edition the very next year. However, it wasn't published in English until 1841. This English translation was not very good and often changed the original meaning. Today, a more modern translation of the Description is available, which is helpful for understanding Van der Donck's observations about Native American beliefs.

Return to New Amsterdam

After years of stopping Van der Donck from sailing, the Dutch West India Company finally agreed on May 26, 1653, to let him return home to his family. But there was a condition: he had to stop his public political work. The Company sent a request to its directors saying Van der Donck would "resign the commission previously given to him as President of the community... and...to accept no office whatever it may be, but rather to live in private peacefully and quietly as a common inhabitant."

However, once he arrived, giving up public office wasn't enough. He was then stopped from practicing law because there was no one else "of sufficient ability and the necessary qualifications" to be his equal. These rules didn't seem to stop his behind-the-scenes efforts. Another political uprising against Stuyvesant happened just weeks after Van der Donck returned. In December, he had to ask for protection from Stuyvesant.

There is no exact record of Van der Donck's death. He was alive and 37 years old in the summer of 1655. He was mentioned as deceased in a court case on January 10, 1656. This case was about who owned two Bibles taken from his house by Native Americans. His widow provided a statement in that case. He likely died on his estate, perhaps peacefully. If he had died violently during one of the Native American raids in September 1655, it would probably have been noted in the court records. He was survived by his wife and his parents, whom he had convinced to move to the colony.

Legacy

For a long time, the English translation of Van der Donck's Description of New Netherland was known to be "defective" and "inept." But until 2008, it was the only one available. Still, Mariana Van Rensselaer called Van der Donck's book "an exceptionally intelligent book of its kind," especially praising its quality as a natural history study. Its quality as a study of cultures has also been praised by experts.

Even though the English eventually took over the colony, New Amsterdam kept the city charter that Van der Donck had fought for. This charter included unique Dutch features, like a guarantee of free trade.

In his 2004 book The Island at the Center of the World, author Russell Shorto wrote that Van der Donck's character and actions were important to the development of the American spirit. He called Van der Donck a "forgotten American patriot."

The author J. van den Hout, in his book Adriaen van der Donck: A Dutch Rebel in Seventeenth Century America, stated that Van der Donck has been called a hero, a visionary, and a spokesman for the people. At the same time, he has also been described as arrogant and selfish, thinking only of his own goals.

See also

In Spanish: Adriaen van der Donck para niños

In Spanish: Adriaen van der Donck para niños

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |