Alasdair MacIntyre facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Alasdair MacIntyre

|

|

|---|---|

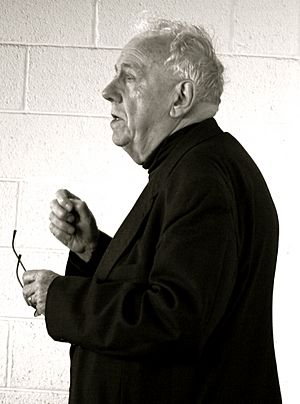

MacIntyre in 2009

|

|

| Born |

Alasdair Chalmers MacIntyre

12 January 1929 Glasgow, Scotland

|

| Died | 21 May 2025 (aged 96) |

| Alma mater |

|

|

Notable work

|

|

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Institutions | |

| Academic advisors | Dorothy Emmet |

| Influences | |

| Influenced |

|

Alasdair Chalmers MacIntyre (12 January 1929 – 21 May 2025) was an important Scottish-American philosopher. He made big contributions to moral philosophy (how we decide what is right or wrong) and political philosophy (how societies should be organized). He also studied the history of philosophy and theology.

MacIntyre's book After Virtue (published in 1981) is considered one of the most important works in English-speaking moral and political philosophy from the 20th century. He taught at many universities, including the University of Notre Dame and London Metropolitan University.

Contents

About Alasdair MacIntyre

Alasdair MacIntyre was born in Glasgow, Scotland, on January 12, 1929. He studied at Queen Mary College, London, the University of Manchester, and the University of Oxford. He started teaching in 1951 in Manchester.

He taught at several universities in the United Kingdom before moving to the United States around 1969. MacIntyre taught at many different universities in the US, including:

- Brandeis University

- Boston University

- Wellesley College

- Vanderbilt University

- University of Notre Dame

- Duke University

He was also the president of the American Philosophical Association. In 2010, he received the Aquinas Medal, a special award from the American Catholic Philosophical Association. He was a member of several important academic groups, like the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

From 2000, he was a professor at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana. Even after he retired from teaching in 2010, he continued his research there. He often gave public talks, including a main speech at the de Nicola Center for Ethics and Culture's Fall Conference.

MacIntyre was married three times and had children. He passed away on May 21, 2025, in South Bend, Indiana, at the age of 96.

MacIntyre's Ideas on Morality

MacIntyre's way of thinking about moral philosophy is quite detailed. He wanted to bring back an older way of thinking about morals, based on the idea of "virtues" from the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle. He believed his approach was a "peculiarly modern understanding" of this task.

Understanding Moral Debates

MacIntyre's modern approach helps us understand moral disagreements. Unlike some philosophers who try to find one single, logical way to agree on morals, MacIntyre looked at the history of ethics. He saw that different moral ideas often can't be compared using the same rules.

He followed thinkers like G. W. F. Hegel and R. G. Collingwood. MacIntyre believed there are "no neutral standards" that everyone can use to decide what is right or wrong in moral philosophy.

Why Modern Morality is Confusing

In his most famous book, After Virtue, MacIntyre explained why modern moral discussions can be confusing. He argued that thinkers from the Age of Enlightenment tried to create a universal moral code that didn't rely on a purpose or goal for human life. When this failed, some later philosophers, like Friedrich Nietzsche, thought that moral reasoning was impossible.

MacIntyre showed that this overemphasis on pure reason led to Nietzsche's idea that there's no real moral truth.

Bringing Back Virtue Ethics

MacIntyre tried to find more modest ways of thinking about morals and arguing about them. These ways don't claim to be perfectly logical or certain. But they can stand up against ideas that say all morals are relative or just feelings.

He brought back the ideas of Aristotelian ethics. This way of thinking focuses on the purpose or goal of good actions. He found this idea fully developed in the writings of Thomas Aquinas, a medieval philosopher. MacIntyre believed this Aristotelian-Thomistic way of thinking offers "the best theory so far" for understanding how things are and how we should act.

Traditions of Thought

MacIntyre believed that moral arguments always happen within different "traditions" of thought. These traditions are like ongoing discussions over time. They have shared ideas, ways of thinking, and types of arguments.

Even if different traditions can't logically prove each other wrong, they can still challenge each other. They can question if another tradition's ideas make sense internally, how it solves problems, and if it leads to good results.

Key Books by MacIntyre

After Virtue (1981)

This is probably MacIntyre's most widely read book. He wrote it when he was in his fifties. Before this, he was known as an analytic philosopher with some Marxist ideas. He used to look at moral problems one by one.

However, after reading books by Thomas Kuhn and Imre Lakatos about the philosophy of science, MacIntyre changed his whole approach. He decided to look at modern moral and political philosophy from the viewpoint of Aristotle's ideas about moral and political life.

In After Virtue, MacIntyre explains why modern moral discussions often don't work well. He also tries to bring back the idea of purpose-driven thinking found in Aristotelian virtue ethics. He argued for protecting local communities and their traditional ways of life from the negative effects of the free market.

Whose Justice? Which Rationality? (1988)

In this book, MacIntyre explored his idea of "traditions" more deeply. He argued that different ideas of justice come from different ways of thinking about what is reasonable. These different ways of thinking are part of "socially embodied traditions of rational inquiry."

MacIntyre defined a tradition as "an argument extended through time in which certain fundamental agreements are defined and redefined." This happens through both internal discussions and debates with outside ideas.

The book gives examples of different traditions, like Aristotelian, Augustinian, Thomist, and Humean. He showed how these traditions can split, combine, or challenge each other. He argued that even if these traditions are very different, they can still engage with each other. One way is by showing how a rival tradition might have problems or "epistemic crises." Another way is by solving problems within one's own tradition that others cannot.

MacIntyre also argued that all human thinking happens within a tradition, whether we know it or not. He said that even though different traditions have very different ways of thinking, this doesn't mean that all truth is relative.

Three Rival Versions of Moral Inquiry (1990)

This book is often seen as the third part of a series that started with After Virtue. MacIntyre looked at three main ways of thinking about morals that are common today. He linked each to an important book from the late 1800s:

- The Encyclopædia Britannica (representing a broad, factual approach)

- Friedrich Nietzsche's Genealogy of Morals (representing a critical, historical approach)

- Pope Leo XIII's Aeterni Patris (representing a traditional, religious approach, specifically Thomism)

MacIntyre's book critiques the first two approaches. He tried to show that Thomism (the philosophy of Thomas Aquinas) is the most convincing way to think about morals. He also suggested ways to improve how universities teach and how people do research, encouraging different traditions to engage with each other.

Dependent Rational Animals (1999)

In After Virtue, MacIntyre talked about virtues based on social practices and individual journeys. But in Dependent Rational Animals, he tried to connect virtues to human biology, following the ideas of Thomas Aquinas. He realized that ethics cannot be completely separate from biology.

He argued that "human vulnerability and disability" are key parts of human life. He said that "virtues of dependency" are needed for people to grow from babies to independent adults and then to old age. He wrote: "It is most often to others that we owe our survival, let alone our flourishing... The virtues that we need, if we are to develop from our animal condition into that of independent rational agents, and the virtues that we need, if we are to confront and respond to vulnerability and disability both in ourselves and in others, belong to one and the same set of virtues, the distinctive virtues of dependent rational animals."

MacIntyre looked at scientific texts on human biology. He wanted to challenge the idea of a completely independent, thinking person who decides moral questions alone. He called this the "illusion of self-sufficiency." Instead, he showed that our need for others is a key part of being human. This need reveals why certain virtues are important for us to become independent thinkers.

What is Virtue Ethics?

MacIntyre was a very important person in bringing back interest in virtue ethics. This idea focuses on the main question of morality: how to live a good life by developing good habits and knowledge. His approach suggests that good judgment comes from having a good character. Being a good person isn't just about following rules.

MacIntyre saw himself as updating Aristotle's idea of an ethical teleology (meaning a purpose or goal). He stressed the importance of "internal goods" or "goods of excellence." These are good things that come from being part of a community and doing things well within a "practice" (like playing a sport or being a doctor). This is different from focusing on rules (which is deontological ethics) or the results of actions (which is utilitarianism).

Before MacIntyre, virtue ethics was mostly linked to older philosophers like Plato, Aristotle, and Thomas Aquinas. MacIntyre argued that Aquinas's ideas, which combined Augustine's and Aristotle's thoughts, were more insightful than modern moral theories. Aquinas focused on the telos (the end or completion) of social practices and human life. Within this framework, we can judge if actions are moral. His main work on virtue ethics is his 1981 book, After Virtue.

MacIntyre believed that virtues add to, rather than replace, moral rules. He even described some moral rules as "exceptionless," meaning they always apply. He saw his work as different from general "virtue ethics" because he emphasized that virtues are part of specific, historical social practices.

MacIntyre's Political Views

MacIntyre's ideas about ethics also shaped his political views. He defended the "goods of excellence" that come from practices. He argued against the modern pursuit of "external goods" like money, power, and status. These external goods are often the focus of modern institutions that follow rules or aim for usefulness, like those described by Max Weber.

He was called a "revolutionary Aristotelian" because he combined ideas from his Marxist past with those of Thomas Aquinas and Aristotle. This happened after he became a Catholic. For MacIntyre, liberalism and postmodern consumerism not only support capitalism but also help it continue. However, he also criticized Marxism, saying that Marxists often ended up using ideas similar to Kantianism or utilitarianism. He believed that when Marxists gained power, they tended to become like Weber's ideas of bureaucracy.

MacIntyre's ideas helped make Aristotelianism less about being elite. He argued that moral excellence isn't just for a specific historical practice in ancient Greece. Instead, it's a universal quality for anyone who understands that good judgment comes from having a good character.

In his early life, MacIntyre was involved in different political groups. He was briefly a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain and later of the Socialist Review Group.

MacIntyre's Religious Views

MacIntyre became a Catholic in the early 1980s. After this, his work was influenced by what he called an "Augustinian Thomist approach to moral philosophy."

In an interview, MacIntyre explained that he became Catholic in his fifties. This happened because he became convinced that Thomism (the philosophy of Thomas Aquinas) was true, even while he was trying to show his students that it wasn't. In his book Whose Justice, Which Rationality?, he also described how a person might be "chosen" by a tradition, which might reflect his own journey to Catholicism.

More details about MacIntyre's views on philosophy and religion can be found in his essays like "Philosophy recalled to its tasks" and "Truth as a good." He also wrote a history of Catholic philosophy in his book God, Philosophy and Universities.

Works by Alasdair MacIntyre

- 1953. Marxism: An Interpretation.

- 1958, 2004. The Unconscious: A Conceptual Analysis.

- 1966, 1998. A Short History of Ethics.

- 1968, 1995. Marxism and Christianity.

- 1971. Against the Self-Images of the Age: Essays on Ideology and Philosophy.

- 1981, 2007. After Virtue.

- 1988. Whose Justice? Which Rationality?

- 1990. Three Rival Versions of Moral Enquiry.

- 1999. Dependent Rational Animals: Why Human Beings Need the Virtues.

- 2005. Edith Stein: A Philosophical Prologue, 1913–1922.

- 2006. The Tasks of Philosophy: Selected Essays, Volume 1.

- 2006. Ethics and Politics: Selected Essays, Volume 2.

- 2009. God, Philosophy, Universities: A Selective History of the Catholic Philosophical Tradition.

- 2016. Ethics in the Conflicts of Modernity: An Essay on Desire, Practical Reasoning, and Narrative.

See also

In Spanish: Alasdair MacIntyre para niños

In Spanish: Alasdair MacIntyre para niños

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |