Alaska–Yukon–Pacific Exposition facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Alaska–Yukon–Pacific Exposition |

|

|---|---|

The Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition with a view of Mount Rainier

|

|

| Overview | |

| BIE-class | Unrecognized exposition |

| Name | Alaska–Yukon–Pacific Exposition |

| Visitors | over 3,700,000 |

| Location | |

| City | Seattle |

| Coordinates | 47°39′14″N 122°18′28″W / 47.6537965°N 122.3077869°W |

| Timeline | |

| Opening | June 1, 1909 |

| Closure | October 16, 1909 |

The Alaska–Yukon–Pacific Exposition was a big event, like a world's fair, held in Seattle in 1909. Its main goal was to show how much the Pacific Northwest region was growing.

The fair was first planned for 1907. This was to celebrate 10 years since the Klondike Gold Rush. But the organizers found out about another big fair, the Jamestown Exposition, happening that year. So, they decided to move their fair to 1909.

After the fair ended, its grounds became the campus for the University of Washington.

Contents

Planning the Big Fair

The idea for the fair came from Godfrey Chealander. He worked with the Alaska Territory exhibit at a fair in Portland, Oregon, in 1905. He first suggested a permanent exhibit in Seattle about Alaska. This idea grew into a plan for a large exposition.

James A. Wood, an editor at the Seattle Times, also wanted a big fair. He wanted it to be as grand as the one in Portland. Soon, the Times publisher, Alden J. Blethen, supported the idea. John Edward Chilberg, a well-known Seattle merchant, became the president of the Exposition.

Edmond S. Meany suggested holding the fair on the University of Washington campus. In 1905, the campus was mostly forest with only three buildings. It seemed far from the city center back then. But Meany convinced others that the forest itself would be an attraction. He also knew the fair's buildings and landscaping would greatly help the university.

The Washington State Legislature supported the fair. They said it must create at least four permanent buildings. King County, Washington, where Seattle is, gave $300,000 for a forestry exhibit. This exhibit was the largest log cabin ever built.

Since the Klondike gold strikes were in Canada, the fair's name became "Alaska-Yukon Exposition." Later, the Seattle Chamber of Commerce added "Pacific" to the name. This showed the importance of trade with Asian countries. The fair became known as the "A-Y-P" for short.

Moving the fair from 1907 to 1909 was a good decision. The year 1907 had a bad economy. If the fair had happened then, it likely would have lost money. But in 1909, it was a big success!

Designing the Fairgrounds

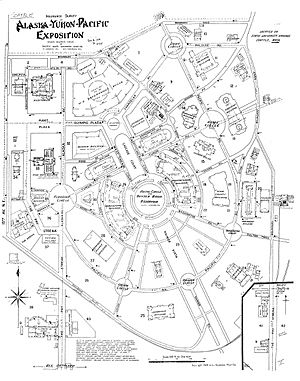

The Olmsted Brothers firm from Massachusetts planned the Exposition. They were already designing parks in Seattle. John C. Olmsted visited Seattle in 1906. He saw Mount Rainier in the distance. He decided to make the mountain the main focus of the fair's layout. This main view is now called the Rainier Vista on the University of Washington campus.

James Frederick Dawson was the main landscape architect for the fair. His design included a long pool with small waterfalls along Rainier Vista. Howard and Galloway, an architecture firm from San Francisco, oversaw the construction of the fair's buildings. They designed some buildings and managed others.

The fairgrounds were completely ready for the opening day on June 1, 1909.

Exciting Exhibits

Only Japan and Canada built their own buildings at the fair. But their presence, along with exhibits from Hawaii and the Philippines, helped show the "Pacific" theme. Other countries had smaller displays.

The King County exhibit was very popular. It had a small model of a coal mine from nearby Newcastle. It also showed detailed scenes of Seattle. The Woman's Building showed the important role of women in settling the Western United States. It also highlighted their charity work.

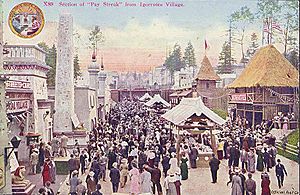

The "Pay Streak" was the fair's fun area. It was like a carnival with games and rides. There was even a show that recreated a famous American Civil War naval battle.

-

A display of Southern California fruits.

-

Installing the statue of George Washington that is still on campus today.

-

The Japanese style torii gate at the South entrance.

Opening Day Excitement

The fair gates opened at 8:30 AM on June 1, and people rushed in. At 9:30 AM, military bands played music. Many people sat in the fair's amphitheater. They waited for a special signal from Washington D.C.

At noon in Seattle, President Taft officially opened the Exposition. He touched a special gold telegraph key. This key had gold nuggets from the first mine in the Klondike. When the signal arrived at the fairgrounds, a gong rang five times. A large American flag was unfurled, and there was a twenty-one gun salute. These grand events announced the fair was officially open!

Visitors and Crowds

Opening Day, June 1, was a city holiday. About 80,000 people came to the fair. Even more people, 117,013, visited on "Seattle Day." Other popular days were dedicated to different groups of people, clubs, and U.S. states. By the time the fair closed on October 16, over 3,700,000 people had visited!

Spreading the Word: Publicity

The fair had its own team to promote it. They used newspapers and magazines to tell everyone about the upcoming event. In early 1908, Seattle newspapers said the publicity was working well. The fair was getting good mentions across the United States.

The publicists said this fair would be much better organized than the 1907 Jamestown Exposition. They promised amazing entertainment. Many newspapers were interested that this fair would not need money from the U.S. government. The fair's leaders only asked the U.S. to build exhibits like any other country.

Throughout 1908, as new exhibits were built, news about the fair's progress was sent out. Newspapers often printed these updates exactly as they were written. For example, a newspaper in Tampa, Florida, wrote about motor boat races at the fair. The article said the pavilion for the event was on "one of the prettiest spots on the exposition's shoreline." It praised the area for being perfect for motor boating all year.

By early 1909, the focus shifted to who would attend. Many local newspapers wrote about people planning to travel to Seattle. Several big newspaper meetings were also planned for the west coast. Editors were very interested in visiting the fair. The fair's organizers also benefited from railroad advertisements. These ads encouraged people to travel by train to Seattle. One ad for the Great Northern Railway called the train route "attractive." It promised a scenic trip "over the Rockies and through the Cascades" to "the World's Most Beautiful Fair."

Lasting Legacies

The biggest lasting impact of the Alaska–Yukon–Pacific Exposition is how it shaped the University of Washington campus. The Rainier Vista and Drumheller Fountain, which were central to the fair, are now the main focus of the university's Science Quadrangle.

Most of the fair's buildings were meant to be temporary. But some were built to last longer. The Fine Arts Palace was designed as a chemistry building. During the fair, it showed art. After the fair, it became the university's main chemistry building. It was named Bagley Hall. Today, after many updates, it is called Architecture Hall.

The A-Y-P Women's Building also still stands. During the fair, it had exhibits about women. Today, it is called Cunningham Hall. It is one of the few buildings on campus named after a woman. The building now hosts programs related to women.

Other fair buildings lasted for a while but were later taken down as the university grew. The Forestry Building was removed because its natural logs were hard to maintain. It stood where the current Husky Union Building (HUB) is now. The original Meany Hall was damaged by an earthquake in 1965 and later demolished. The Hoo-Hoo-House was a clubhouse for lumbermen. After the fair, it was the faculty club until a new one was built in 1958–60.

Another legacy was the increased fame of fair president J. E. Chilberg. He was a respected banker, but not one of the city's top elite. He was chosen for his ability to get things done. Suddenly, his parties became major social events. He and his wife dined with a relative of the emperor of Japan and hosted a French ambassador.

The statue of William H. Seward, first put up for the fair, is now in Volunteer Park.

William E. Boeing, who founded Boeing, said he saw a flying machine for the first time at the Alaska–Yukon–Pacific Exposition. This made him very interested in aircraft.

Anniversary Celebrations

The year 2009 marked 100 years since the Alaska–Yukon–Pacific Exposition. The City of Seattle and the University of Washington held many events to celebrate this anniversary.

A documentary called "AYP-Seattle's Forgotten World's Fair" was made by John Forsen for PBS.

On July 4, 2009, a group of 12 cyclists started a 1,000-mile bike ride. They rode from Santa Rosa, California, to Seattle, Washington. This ride, called Wheels North, was a tribute to a similar bike trip made in 1909. The ride ended at Drumheller Fountain, a lasting part of the 1909 fair.

Images for kids