Alexander Herrmann facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Alexander Herrmann

|

|

|---|---|

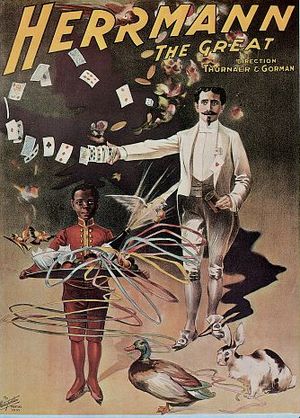

Herrmann the Great

|

|

| Born | February 10, 1844 |

| Died | December 17, 1896 (aged 52) Ellicottville, New York, U.S.

|

| Occupation | Magician, illusionist |

Alexander Herrmann (born February 10, 1844 – died December 17, 1896) was a famous French magician. He was widely known as Herrmann the Great. Alexander was married to another talented magician, Adelaide Herrmann, who was often called the Queen of Magic.

Contents

- The Life of Alexander Herrmann: A Great Magician

- Early Life and Family

- Compars "Carl" Herrmann: Alexander's Mentor

- Alexander's Independent Career

- Marriage and Becoming an American Citizen

- A Typical Herrmann Magic Show

- Herrmann the Great: A World Tour

- Magic Rivalries: The Paper Wars

- The Dangerous Bullet Catch Trick

- The Death of a Great Magician

- The Herrmann Legacy in Magic

- See also

The Life of Alexander Herrmann: A Great Magician

Early Life and Family

Alexander Herrmann was born in Paris, France. He was the youngest of sixteen children. His father, Samuel Herrmann, was a German Jew, and his mother, Anna Sarah (Meyer) Herrmann, was of Breton descent. People said that Samuel Herrmann was a physician who sometimes performed magic shows across Europe.

Samuel Herrmann: A Doctor and Magician

According to his family, Samuel Herrmann was a part-time magician and a full-time doctor. He was very popular with the Sultan of Turkey, who often asked him to perform. The Sultan paid him a lot of money for his shows. It was also said that Samuel's magic shows in Paris became so famous that even Napoleon wanted to see him perform. Napoleon supposedly gave Samuel a gold watch for his performance. Alexander Herrmann carried this gold watch on the day he died, and it was later given to his wife. Eventually, Samuel's medical work took up too much of his time, so he stopped doing magic completely.

Samuel Herrmann settled down in Germany in 1816 when his oldest son, Compars, was born. He moved his family to France and performed in Paris until 1855. He taught his magic skills to Compars, who was also known as Carl. Samuel continued to perform even after Carl became a successful magician. Samuel retired from magic around 1860.

Compars "Carl" Herrmann: Alexander's Mentor

Alexander's older brother, Compars Herrmann, left medical school early to become a magician. He was a big inspiration for Alexander. In 1853, when Carl returned home to Paris, he was excited to see that his eight-year-old brother Alexander was already interested in magic. Without his family's permission, Carl "kidnapped" Alexander and took him to Saint Petersburg, Russia, to teach him magic. They started a tour together in Russia.

Alexander stayed with Carl until they reached Vienna. Their mother came there and insisted that Alexander return to Paris. They agreed that Alexander would stay with Carl until the tour ended. Alexander's jobs included floating horizontally on a rod, acting as a blindfolded medium, and appearing from an empty box. During their trip through Europe, Carl taught Alexander advanced sleight of hand tricks. Some of these tricks Carl learned from their father, and others he figured out himself.

Alexander was a very eager student. After touring places like Germany, Austria, Italy, and Portugal, the tour finished in Vienna. Carl settled in Vienna and, as he promised, sent Alexander home to their parents in Paris. Back in Paris, Alexander showed his father what he had learned from Carl. Samuel was so impressed with Alexander's skills that he let him continue with magic. Alexander stayed in Paris until he was about 11 years old. Then he returned to Vienna to meet Carl, who continued to teach him. Carl had promised Samuel to teach Alexander other things besides magic, so Alexander also attended college in Vienna. But his main interest remained sleight of hand.

Alexander Joins Carl's Show

Alexander went with Carl on almost every tour. At first, he was Carl's assistant. This time, he didn't float on a horizontal pole. Carl got rid of the equipment from his last tour because French magician Robert-Houdin claimed they were his tricks. Carl then focused on tricks that used pure sleight of hand.

As Alexander's skills grew, he became a more important part of Carl's show. By the time they came to the United States in 1860, Alexander was seventeen. Audiences noticed how skillful he was; his tricks soon became as good as his famous brother's.

They performed at the Academy of Music in Brooklyn. This place was known for new and exciting shows. The posters at the time said that Herrmann's shows were special because they didn't use any big machines. All the tricks were done with amazing hand skills. They still performed Houdin's "Second Sight" trick, with Alexander helping Carl on stage. Carl introduced Alexander to the audience as his future replacement. Then Alexander performed a "card scaling" (card-throwing) act.

Alexander became so good at card-throwing that he could throw a card into the lap of any audience member who raised their hand. He could also bounce cards off the back wall of the biggest theaters. He developed a way to throw cards all the way to the back of the theater, which really impressed the people in the cheaper seats.

Carl's shows were very successful, bringing in a lot of money. When the American Civil War started, the Herrmanns left the United States for Central and South America. A few years later, they went their separate ways. Alexander performed on his own until he met Carl again in Vienna in 1867. They formed a new partnership and returned to the U.S. to continue their tour. The Herrmann name became very well known for magic. Eventually, the two magic brothers went their separate ways again.

Alexander's Independent Career

Alexander started his own magic career in 1862. Carl went back to perform in the big cities of Europe. Alexander brought his show to London in 1871 and performed for three years at Egyptian Hall. He called this time his "one thousand and one nights." Egyptian Hall was one of the first buildings in England to look like ancient Egyptian temples. By the late 1800s, the Hall was also famous for magic shows. So, when Alexander started performing there, it was a sign that he was a top professional magician.

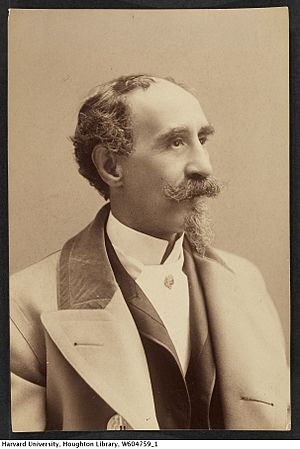

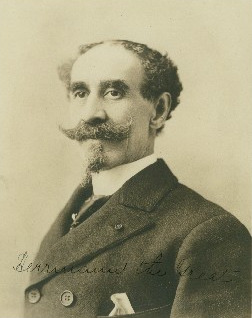

As he got older, Alexander started to look like his brother Carl. Carl had a beard and a mustache, and his hair was thinning. Alexander had curly hair, a thick goatee, and a mustache with upturned ends. Even though they looked alike, Alexander had his own unique and exciting personality. Carl's humor was subtle, and he presented his magic in a mysterious way. Alexander, on the other hand, mixed comedy with his magic. He was a humorist who wanted his shows to be joyful and fun.

Herrmann believed that a magician's success came from people's belief. He said, "Whatever mystifies, excites curiosity; whatever in turn baffles this curiosity, works the marvelous."

Even with his funny acts, Alexander still amazed his audiences. His intense eyes, big mustache, and goatee made him look like a classic magician. People said he created an "atmosphere of mystery." But he was also known as a very kind and gentle person.

There were rumors that Carl was Alexander's uncle, or that they weren't related at all. A lawsuit even claimed Alexander's real name was Nieman, and that Carl had adopted him. In 1895, Alexander told a San Francisco newspaper that he was born in France on February 11, 1843, to German parents. (However, records show he was born on February 10, 1844.) He said his father was a doctor in Germany who moved to Paris before Alexander was born. These rumors continued even after his death, and Alexander's wife had to deny them many times.

Carl retired during Alexander's three-year show at Egyptian Hall. While in America, Alexander learned how important it was to get attention from the press. He used this skill in London. One day, while walking down Regent Street with a friend, he gathered a crowd. He cleverly took a handkerchief from one gentleman and a watch from another. He did this so that two policemen would notice him.

When the policemen came over, Alexander pretended to be innocent and asked them to search him. They found nothing. Herrmann then suggested the policemen search themselves. The handkerchief was found on one officer, and the watch on the other! Then one policeman realized his badge was missing. They searched one of the gentlemen in the crowd and found the badge. Herrmann smiled and said, "It seems that I am the only honest person here."

He tried to explain that it was just a magician's joke, but the police didn't believe him. They took him to the police station. There, he was recognized and set free. The London newspapers loved the story and made it a huge sensation. The whole town laughed at the joke Herrmann had played on the police.

Herrmann was very outgoing and made friends easily. He was popular with both men and women. One woman he met was a 22-year-old dancer from London named Adelaide Scarcez. Most of his friends were from the theater world.

Alexander's successful show in London eventually ended. He then toured Europe, and later returned to the United States and Canada for several tours. Meanwhile, his brother Carl lost a lot of money during the financial panic of 1873. Carl needed money badly, so he had to start performing again to pay his debts.

Marriage and Becoming an American Citizen

In 1874, Alexander returned to America. On the boat, he saw Adelaide Scarcez, the young dancer he had met in London. Adelaide had planned to marry an American actor, but she changed her mind before the ship docked.

On March 27, 1875, Alexander and Adelaide were married by the Mayor of New York in Manhattan. Herrmann was known for doing spontaneous tricks. Even on his wedding day, he couldn't resist; he pulled a roll of money from the mayor's beard!

Sometimes his jokes didn't go as planned. Once, he was having dinner with a journalist named Bill Nye. Herrmann found a large diamond in Nye's salad. Nye, being a humorist, turned the tables on the magician. He picked up the diamond and gave it to a passing waitress as "a little present." Herrmann had a hard time getting his diamond back from the waitress, and the restaurant owner had to convince her to return it.

In New York, Alexander wanted to buy a home, but only American citizens could do so. So, he became a naturalized citizen in July 1876 in Boston. Later, he bought a beautiful, dark red mansion in Whitestone, Queens, New York. The property was surrounded by an eight-foot-high, spiked wire fence. You could see cattle and goats grazing in the fields along the winding, tree-lined road.

When friends visited from Europe, he would pick them up in his yacht, Fra Diavolo. He also had his own private train car waiting at the Whitestone Depot, along with two baggage cars for his equipment. The private car cost him a lot of money.

A Typical Herrmann Magic Show

As Alexander's brother Carl got older, his shows became smaller. Alexander, however, made his shows bigger and more grand. Here's what a typical Herrmann show might have looked like:

After a lot of exciting music from the orchestra, Herrmann would enter. He wore fancy black velvet evening clothes, a top hat, and white gloves. The audience would clap, and he would bow and smile.

He would take off his gloves and make them disappear between his hands. Herrmann would then show two metal cones and a beautiful brass vase. He would open the lid of the vase and show a bag of rice. Audience members would be invited to examine all the items.

After the items were returned, Herrmann would pour the rice into the vase and put the lid on. He would walk into the audience, go up to a man with a beard, and borrow his hat. He would then reach into the gentleman's beard and pull out an orange, saying, "Thank you. Just what I needed for this trick!" This would make the audience laugh. He would return to the stage, place the hat on a chair, and the orange on a table.

Herrmann would ask the audience which cone they preferred, "The right one or the left?" He would take the chosen cone and place it on the hat. "I will make the rice and orange switch places," he would announce.

After some playful actions where he pretended to sneak the orange away from the cone, he would decide not to use the cone at all. He would leave the cone on the empty hat and place the orange on the table. After making a magical pass, he would lift the cone, and a pile of rice would appear on top of the hat. He would then pick up the orange and make it disappear in his hands. Finally, he would lift the vase that had contained the rice and show the missing orange inside.

From there, he would casually show his hands were empty and then produce a fan of cards from behind his knee. With these cards, he would perform a series of sleight of hand tricks. He would end the card act by having three people from the audience choose cards. He would place the deck into a goblet. From the goblet, the chosen cards would rise one by one. He would then take the deck out of the goblet, toss them, and they would seem to melt in mid-air.

He would pretend he was done with cards, but his empty hands would soon be full of them again. He would take each one and throw them into the audience. Herrmann would ask an audience member to call out for a card, and he would accurately toss it to them, sometimes even to the very top row of the theater.

Herrmann would then pick up the silk top hat he had borrowed from an audience member. One by one, he would produce many silver dollars from the air. After each shining coin caught the spotlight, he would toss it into the hat with a clear clinking sound. He would produce a large number of dollars until the hat was full. Herrmann would pour the coins into a silver tray and show it to the audience. From there, the coins would be dumped into a paper bag. He would wrap it up and toss it to the owner of the hat. The silver dollars would have changed into a box of candy!

A piece of paper would be left over from the package. Herrmann would pick this up and roll it into a ball. Then he would make it seem to pass through his knee. In an instant, he would toss the ball of paper into the air, where it would vanish.

Herrmann would pick up the hat again and discover many things inside—enough to fill a whole trunk! He would thank the owner of the hat as he returned it. As he did, he would find a white rabbit inside. Herrmann would stroke the rabbit. He would then seem to pull it apart and have two rabbits, one in each hand. He would put the rabbits on the table. "If you notice," he would say in his Parisian accent, "the rabbits are the same size, no?" He would scoop them from the table, and they would melt into one.

"Now, you notice that the rabbit, she is much fatter," he would say. He would pick up a pistol from the table. He would toss the rabbit into the air and shoot at it. The rabbit would be gone. He would quickly go down to the aisle into the audience. He would then pull the vanished rabbit from the coattails of a spectator!

As he walked back to the stage, the curtain would close behind him. He would stand in front of the curtain and hold the rabbit like a baby. He would talk to the rabbit. The rabbit would turn its head toward Herrmann and cock up one ear, as if it didn't understand. This would make the audience laugh and applaud.

The orchestra would play faster music, and Herrmann would exit. Madame Herrmann would then enter, performing a fire dance. Alexander Herrmann would catch his breath, and the rest of the show would continue.

To do most of his tricks in the first part of the show, Herrmann used a method called "body loads." This is one of the main principles of sleight of hand. Herrmann would carry hidden items on his body and inside his coat, placing them where he needed them for the tricks.

One evening, Herrmann was backstage in his dressing room after preparing his jacket. He had draped his tailcoat over his chair. He was talking to the theater manager, who also had his jacket off. When the first bell rang for the show to start, the manager got up, put on his coat, and left.

Herrmann put on his coat and gloves as he walked toward the stage. The music played his entrance march, and he walked onto the stage. He took his bow and started his opening act. He took off his gloves to make them disappear when he realized something was wrong: he wasn't wearing his own coat! Without his coat, he couldn't do the first act. Instead of panicking, he put his gloves aside and picked up a deck of cards from the table.

He performed some elegant card flourishes with them. As he was finishing with some fancy cuts, he wondered about his coat. Suddenly, he knew the answer. The theater manager was also wearing a full dress suit. He must have taken Herrmann's coat by mistake. He gave the deck a final flourish. He snapped his fingers toward the side of the stage. One of his assistants came on stage. Herrmann was throwing cards out to the audience. He leaned over to the assistant and whispered, "Find the manager. He's wearing my coat." He threw a few more cards until half the deck was left. He added, "And bring me more cards." The assistant left.

Herrmann took the next card and held it between his first and second finger of his left hand. Then he flicked his wrist, sending the card sailing into the audience. He then threw two or three more cards quickly into the audience. His assistant came back with a few more cards. He told Herrmann that someone had been sent to look for the manager. Herrmann took the cards and threw those too. He told his assistant to bring more cards.

The audience was waving for them. So he threw them with great speed, one after another. He threw a few up to the balcony into the hands of waiting spectators. The audience was getting excited about his amazing aim. More cards were brought on. He was told that they were still trying to find the manager. Herrmann was throwing cards to the farthest parts of the theater with even more accuracy. The audience went wild.

He was down to only a few cards. He was tired and didn't know what else to do to stall for time. He looked toward the side of the stage and saw the surprised manager. Herrmann threw his last card and bowed. The applause was incredibly loud.

He went offstage and quickly took off the manager's jacket. Then he carefully took his own jacket from the startled manager. Herrmann checked the contents. Everything was still in its place. He carefully put on his coat and smoothed it. He walked onto the stage as before. He bowed as the applause grew even louder. Then he went into his original routine.

Herrmann the Great: A World Tour

In 1883, after becoming very famous in the United States, Herrmann started another world tour. His first stop was South America. Emperor Don Pedro II of Brazil attended nineteen of his shows in Rio de Janeiro. The emperor was so amazed by Herrmann's magic that he gave him the Cross of Brazil award.

After touring the rest of South America, Herrmann went to Russia. His tour took him all the way to Siberia. In St. Petersburg, he received a grand welcome. He was invited to a special dinner for the Spanish minister, attended by many important people in Russian society. They toasted his health and declared, "From this moment forth, you will be known as Herrmann the Great."

The newly named Herrmann the Great performed for Czar Alexander III of Russia. The czar was impressed by Herrmann's delicate touch. He picked up a deck of cards and walked over to the magician. He firmly grabbed the deck and tore it in half. He wanted to test Herrmann's skill. He handed the torn deck to the magician to see if he could match the czar's strength. Herrmann was always calm under pressure. He paused for a moment, then placed one half on top of the other and neatly squared them. Then he proceeded to tear both halves together. Czar Alexander was very impressed. He gave Herrmann a watch with a heavy gold chain.

Alexander told an interesting story about something that happened after the performance. He was playing billiards at a saloon with a court official when he noticed the Czar was also playing there. Herrmann shot the ball with all his strength against a large plate-glass mirror that went from the floor to the ceiling. It shattered into fifty pieces. Everyone in the room was horrified, especially Herrmann.

The Czar dismissed Herrmann's apology and said the broken mirror was not important. He ordered the game to continue. With the Czar's permission, Herrmann examined the mirror to see the damage. He hoped to have it repaired.

The Czar teased him, saying if he was such a good wizard, why didn't he make the mirror whole again? That was exactly the hint Herrmann was hoping for. He paused for a moment, then ordered the mirror to be covered with a cloth. After about ten minutes, he quickly pulled away the cloth, and the mirror was completely restored and perfect!

Herrmann later told The North American Review that he would let the reader imagine how he did it.

From Russia, Herrmann returned to France, where he was born. At the Eden Theatre in Paris, his performance was seen by the Prince and Princess of Wales (who later became King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra of England).

Alexander met his brother Carl again in 1885 in Paris. Carl was still a bit annoyed with Alexander because of his success at Egyptian Hall. Carl was planning to retire again and was training their nephew Leon to be his successor. However, he didn't want to retire until he had earned back his money. So, the two brothers made an agreement to divide the world: Compars would return to Europe, and Alexander to the United States.

Alexander left Paris to go back to America, where he became a well-known name. Two years later, while in New York, Alexander was shocked to hear the news of his brother Carl's death on July 8, 1887, in Karlsbad, Germany. Even with their rivalry, Alexander felt he owed everything to Carl. "We've always had a warm and brotherly feeling towards each other," he told a newspaper.

Since Alexander was so famous in the U.S., when news of "Professor Herrmann's" death appeared in the papers, many people thought it was Alexander who had died. He was mourned in the newspapers. Carl did get his money back before he died. Leon took his place and was doing well. Alexander was happy to let Leon take over Europe.

Throughout the 1870s and 1880s, Alexander and his wife Adelaide Herrmann performed together in grand stage shows. A famous American show organizer, Michael B. Leavitt, managed Herrmann's shows in America and Mexico. Leavitt always paid for all travel costs, advertising, salaries, and other expenses. Leavitt once said, "Whenever I open a new theater, if I want to be sure of large crowds, I will have Herrmann the Great play the date." Alexander was always a big draw wherever he performed, earning a large percentage of the ticket sales and making a lot of money each year.

He often spent his money quickly and would ask Leavitt for advances. Leavitt never refused his star. He saw it as a good investment. "The name Herrmann the Great on any theater sign was a sure sign of a successful show."

Alexander and Adelaide traveled with their show by train and mostly stayed in the U.S. They presented a full evening program, performing tricks like Robert Houdin's Ethereal suspension routine, also known as aerial suspension, in an illusion called Trilby. A board would be placed on two chairs, and Madame Herrmann would lie on the board. Both the board and Madame Herrmann would rise into the air. The two chairs would be removed. After a hoop was passed over her, Madame Herrmann would float back down to the two chairs.

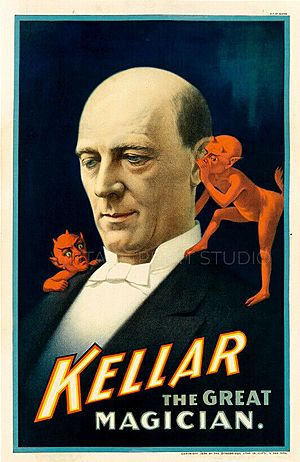

The Herrmanns presented this and many other amazing illusions of the time. Their only rival was Harry Kellar.

Magic Rivalries: The Paper Wars

During the Golden Age of Magic, America usually had only one "King of Magic" at a time. Robert Heller was the first to hold this title. After his death, Harry Kellar tried to follow him. However, because their names were similar, people wrongly thought Kellar had changed his name to benefit from the dead magician's fame. Even though he tried to prove his original name was Keller with an e and that he changed it years ago to avoid confusion with his friend Heller, the public was still not very welcoming to him.

So, Kellar toured the world instead, only visiting his home country occasionally. When he did, he found that the new King of Magic was Herrmann the Great. Kellar tried to take his place, but the American people loved Alexander and his clever humor.

Herrmann knew Kellar wasn't a serious threat, but he still looked down on him. He criticized Kellar's lack of sleight of hand skills and his preference for using mechanical devices. Even for popular tricks like the Miser's Dream, Kellar chose to use a secret device he had created.

Kellar was excellent at misdirection in tricks like the Flower Growth. Two flower pots would be covered by a cone, and then a full bouquet of flowers would appear, as if they had magically grown. The audience never saw any false moves. Herrmann was also a master of misdirection, and as an entertainer, he was unmatched.

Leavitt managed both magicians. There was never a problem until 1888 when Kellar learned about Herrmann's planned tour of Mexico. Kellar asked Leavitt to cancel his American tour so he could perform in Mexico before Herrmann arrived. At first, Leavitt refused, but Kellar was very determined and wouldn't take no for an answer. Leavitt sadly agreed. However, instead of letting Kellar win completely, he used Herrmann to disrupt Kellar's plans.

When Herrmann returned to the United States, he presented his expenses to Leavitt as usual. This time, Leavitt refused to pay them. He claimed that much of the transportation cost was for sending antique furniture and other items back to Herrmann's home in Long Island. A lawsuit followed, which made their relationship difficult.

Whenever Herrmann or Kellar would perform in a town, they would put up large paper banners announcing their arrival. Whoever put up their posters first won that battle. So, they started a series of "paper wars." Herrmann would put up his posters. Then Kellar's team would follow and put up Kellar's posters over them. Herrmann's team would then cover Kellar's, creating a third layer. This would continue until the day of the show; the last poster standing was the winner.

After years of this arguing, they decided to call a truce. They felt the country was big enough for two Kings of Magic. Even with this agreement, the public still preferred Alexander.

The Dangerous Bullet Catch Trick

One of the most dangerous magic tricks is the bullet catch. In this trick, a magician has a spectator mark a bullet and load it into a gun. Then the spectator fires directly at the magician, who appears to catch the bullet—often in their mouth or hand. Magicians often talk about the legend of 12 magicians who have died doing this trick, asking, "Will I be number 13?" Even though magicians often exaggerate, there is real danger with the bullet catch.

A version of this act was created by Herrmann the Great with the help of his assistant, Billy Robinson. (Years later, Billy, performing as Chung Ling Soo, would be killed by the same style of gun.)

Old-fashioned muzzle-loaders were used for the act. The "bullet" was actually a lead ball pushed into the gun with a small amount of gunpowder. When the gun was fired, the gunpowder exploded, making the lead ball shoot forward like a tiny cannonball. In most versions of the trick, either a fake bullet was used, or the real ball was secretly removed just before the gun was fired. What came out of the gun's barrel was just a flash of fire, creating the illusion that a bullet had been shot.

Herrmann the Great performed his own version of the bullet catch. The bullet was still marked, but the danger of the trick was avoided. The gunpowder never got near the firing part of the gun, so the bullet never actually left the gun. The trick was safe—or so Herrmann thought; he would not live long enough to see his former assistant die from it.

However, he made the most of the trick. It wasn't a regular part of his show, but he performed it on special occasions. In May 1896, Herrmann announced he would attempt the bullet catch for the seventh time on stage at the Olympia Theatre as part of a fundraiser for the Sick Babies Fund.

A female reporter was sent to interview Madame Herrmann. She went to the Herrmann Manor for the interview. As she walked in, she heard a voice say, "What do you want?" She turned and saw a black bird on a perch. Just then, a moving skeleton jumped out at her! She shrieked, which brought a maid from down the hall. She then found the Herrmanns waiting for her.

Madame Herrmann said, "I lock myself into my dressing room whenever Alexander faces a firing squad."

"Nonsense," Herrmann the Great said, "I have already caught bullets successfully six times. Seven, you know, is a lucky number." He mentioned that he had applied for a life insurance plan, but that the plan would not cover the trick. Apparently, he hadn't mentioned the bullet-catching stunt when he applied for it.

On the day of the performance, Herrmann looked serious. He wore a white shirt with ruffles on the sleeves. He had five muzzle-loaders marked and loaded. They aimed their rifles at him. Madame Herrmann was nowhere to be seen. Herrmann held a china plate in front of him like a target. When he gave the orders, the guns were fired, and he caught the bullets on the plate. Calmly, he handed the bullets out for examination; they appeared to be the very same bullets.

In 1885, Herrmann returned to America, getting the best deals for any star on tour. He lost a lot of money in bad investments outside of magic. For the upcoming season, he expected to make a large profit.

The Death of a Great Magician

Herrmann the Great was a very generous person, even though he looked a bit mysterious. He was the first magician to perform at Sing Sing prison. He lost a lot of money helping other actors who invested in bad theater projects. When the manager of the Chicago Opera House needed money, Herrmann sent him a check to cover the debt.

On December 16, 1896, Herrmann was finishing a week of shows at the Lyceum in Rochester, New York. He invited an entire school to his afternoon performance. That afternoon, the theater was completely full. Because the crowd was so excited and clapped for him so much, Herrmann made his performance longer.

Between shows, an agent asked him to help pay the overdue hotel bills for a theater company that was stuck in Rochester. Herrmann was touched by this request. Then the agent asked him to buy train tickets for them. Herrmann paid for their train tickets to Manhattan and covered their expenses. He also invited them to his evening show before they left.

After the show, he was the special guest at a dinner given by the Genesee Valley Club. The group from the party was supposed to travel with him on his special train to Bradford, Pennsylvania, which was leaving early in the morning. The celebrations lasted until after midnight. He performed for the group, doing card tricks and telling funny stories about his adventures around the world. He said, "My nephew Leon, who is in Paris, will be my successor when I retire."

The next day, he found the train and waved goodbye to his friends who had ridden with him from his private carriage to the railroad station. One of them was a young drama critic for the Rochester newspaper named John Northern Hilliard. (Hilliard later became a leading author on magic in America.) The train trip would be three hours long.

While on board the train to the next performance, Herrmann suffered a heart attack. The train stopped in Ellicottville, New York. Alexander whispered to Adelaide, "Make sure all in the company get back to New York." The local doctor arrived a few moments later, but it was too late. He could not recover. On December 17, 1896, at the age of 52, Herrmann the Great was pronounced dead.

The newspaper articles announcing his death were the most detailed ever written for a magician. Herrmann's body was taken to New York for burial services, and thousands of people attended, trying to get close to the coffin. Herrmann is buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, New York City.

The Herrmann Legacy in Magic

After Herrmann died in 1896, his wife Adelaide continued performing her husband's illusions. On January 11, 1897, she was joined by Alexander's nephew, Leon Herrmann. The Herrmann name still attracted large crowds, but because of disagreements, Leon and Adelaide separated after three seasons and continued with their own shows.

Leon's shows didn't draw as many audiences, and this led to Kellar becoming the top magician in America. Leon later made his show smaller, performing a short act in vaudeville theaters. While on a holiday trip to Paris, Leon died on May 16, 1909.

In contrast, Adelaide Herrmann continued to perform as a successful solo magician for the next 25 years. She became known as "The Queen of Magic." Notably, she continued to perform the dangerous bullet catch trick. Adelaide retired at the age of 75. She died in 1932 and is buried at Woodlawn Cemetery next to her husband.

See also

In Spanish: Alexander Herrmann para niños

In Spanish: Alexander Herrmann para niños