An Essay on the Principle of Population facts for kids

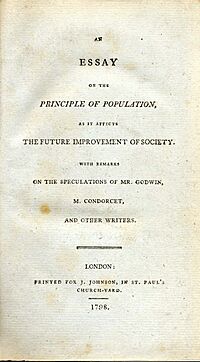

Title page of the original edition of 1798

|

|

| Author | Thomas Robert Malthus |

|---|---|

| Country | England |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | J. Johnson, London |

|

Publication date

|

1798 |

The book An Essay on the Principle of Population was first published in 1798. At first, no one knew who wrote it, but soon the author was identified as Thomas Robert Malthus.

In his book, Malthus warned about future problems. He believed that the human population would grow very quickly, doubling every 25 years. This is called geometric growth. However, he thought that food production would only grow slowly, like adding the same amount each year. This is called arithmetic growth.

Malthus feared that if population grew faster than food, there wouldn't be enough food for everyone. This could lead to hunger and famine. He suggested that birth rates would need to decrease to avoid this.

His book wasn't the first to discuss population, but it sparked a big debate in Britain. It even helped lead to the Census Act 1800. This law made it possible to count everyone in England, Wales, and Scotland every ten years, starting in 1801. This national count is called a census.

Later, in 1826, the 6th edition of Malthus's book was published. It was a major influence on both Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace. They both used Malthus's ideas when they developed their famous theory of natural selection.

A big part of the book explained what is now known as the Malthusian Law of Population. This idea suggests that when the population grows, there are more people looking for work. This can lead to lower wages for workers. Malthus worried that too much population growth would lead to widespread poverty.

Malthus published a much-changed second edition of his work in 1803. He kept updating it, and the final version (the 6th edition) came out in 1826. In 1830, he released a shorter version called A Summary View on the Principle of Population. This shorter book also answered some of the criticisms people had about his main work.

Contents

Understanding Malthus's Ideas

Between 1798 and 1826, Malthus published six different versions of his famous book. He added new information, responded to critics, and shared how his own thoughts on the topic changed over time. He wrote the first book because he disagreed with the very hopeful ideas of his father and his father's friends, like Jean-Jacques Rousseau. They believed society could keep getting better and better.

Malthus also wrote his book to specifically respond to the ideas of William Godwin and the Marquis de Condorcet. These thinkers had very optimistic views about the future of humanity.

Malthus was doubtful that human society could ever become perfect. He noticed that throughout history, some people always seemed to be poor. He explained this by saying that when there's plenty of food and resources, the population grows. But eventually, the population becomes too large for the available resources, which causes problems.

He wrote that people naturally want to have families, which leads to more people. This constant growth often causes hardship for the poorer parts of society. It also stops their lives from getting much better for a long time.

Malthus explained that if a country has just enough food for its people, and then the population grows, the food has to be shared among more people. This means everyone gets less, and many poor people suffer. With more workers than jobs, wages go down, and food prices go up. Workers have to work harder just to earn the same amount.

During these hard times, people might delay marriage or have fewer children. This slows down population growth. When there are fewer workers, wages might rise again. This cycle of good times and bad times for workers would repeat.

Malthus also observed that throughout history, societies faced epidemics, famines, or wars. He believed these events were natural ways that populations were kept in check when they grew too large for their resources.

He wrote that the power of population to grow is much stronger than the Earth's power to produce food. This means that early death must happen in some way. Human problems like crime and war help reduce the population. If those don't work, then diseases and plagues will come. If that's still not enough, then terrible famine will strike, bringing the population down to the level of the food supply.

The very fast growth of the world's population in the last century shows some of the patterns Malthus predicted. His ideas are also used in modern mathematical models that study how societies change over long periods. These are called neo-Malthusian theories.

Malthus's Solutions

Malthus suggested two main ways that population growth is kept in check. The first is a preventive check, which means things that lower birth rates. The second is a positive check, which means things that cause higher death rates.

Positive checks "stop an increase that has already started." These checks mostly affect the poorest people in society. Preventive checks could include delaying marriage or choosing not to marry at all. Positive checks could include hunger, disease, and war.

Malthus also talked about the difference between government help (like welfare) and private charity. He suggested that laws helping the poor, called poor laws, should be slowly removed. He thought this would make people more independent. He believed that poor laws actually made things worse for the poor in the long run. He felt they raised the price of goods and made people less self-reliant. In his words, poor laws tended to "create the poor which they maintain."

Malthus was upset when critics said he didn't care about the poor. In his 1798 book, he showed his concern. He wrote that it's common to hear people say we should encourage population growth. But he believed this was wrong if there wasn't enough food to support more people. He argued that if you want more people, you must first increase food production and improve life for workers. Trying to increase population in any other way, he said, was "vicious, cruel, and tyrannical."

In a later edition (1817), he added that he had written a whole chapter on how to give charity. He said that anyone who read his work fairly would see that he valued kindness and helping others. He denied that he wanted to get rid of charity.

Some people, like William Farr and Karl Marx, argued that Malthus didn't fully understand how much humans could increase food supply. But Malthus himself had written that humans are special because they have the power to greatly increase their means of support.

He also thought about ideas similar to what Francis Galton later called eugenics. Malthus wondered if humans could be improved like animals through careful breeding. He thought things like size, strength, beauty, and even how long people live might be passed down. However, he believed this wouldn't become common because it would mean preventing "bad specimens" from having children.

Malthus on Religion

As a Christian and a clergyman, Malthus thought about how a powerful and caring God could allow suffering. In his first book (1798), he suggested that the constant threat of poverty and hunger taught people to work hard and behave well. He wrote that if population and food grew at the same rate, humans might never have moved beyond a primitive state. He believed that "Evil exists in the world not to create despair, but activity."

Malthus also thought that the variety in nature was designed to help achieve God's purpose and create the most good. However, he didn't believe God wanted people to suffer. Malthus felt that humans themselves were to blame for their suffering.

He believed that God intended the Earth to be full of healthy, good, and happy people. If humans only fill it with unhealthy, bad, and unhappy people, and suffer because of it, then it's not God's fault. It's because humans are not following God's command to "increase and multiply" in a wise way.

Population, Wages, and Prices

Malthus wrote about how population, wages, and prices are connected. When the number of workers grows faster than the amount of food produced, real wages (what your money can actually buy) go down. This happens because more people wanting food makes food prices go up.

When it becomes harder to support a family, people have fewer children. This slows down population growth. Eventually, with fewer workers, wages might rise again.

Malthus explained that the actual value of wages can change even if the money amount stays the same. For example, if workers earn the same amount of money but food prices go up, their money buys less. This means their real wages have fallen, and their lives get harder. But farmers and business owners might get richer because labor is cheaper for them.

In later editions of his book, Malthus made his views clearer. He said that if society relied on suffering (like hunger, disease, and war) to control population, then these problems would always affect society. But if people used "preventive checks" like marrying later, it could lead to a better standard of living for everyone and more stable economic times.

Different Editions of the Book

- 1798: An Essay on the Principle of Population, as it affects the future improvement of society with remarks on the speculations of Mr. Godwin, M. Condorcet, and other writers.. Published without the author's name.

- 1803: Second and much larger edition: An Essay on the Principle of Population; or, a view of its past and present effects on human happiness; with an enquiry into our prospects respecting the future removal or mitigation of the evils which it occasions. Malthus was now named as the author.

- 1806, 1807, 1817 and 1826: Editions 3–6, with only small changes from the second edition.

- 1823: Malthus wrote the article on Population for a supplement to the Encyclopædia Britannica.

- 1830: Malthus had a long part of the 1823 article reprinted as A summary view of the Principle of Population.

The First Edition (1798)

The full title of the first edition was "An Essay on the Principle of Population, as it affects the Future Improvement of Society with remarks on the Speculations of Mr. Godwin, M. Condorcet, and Other Writers."

William Godwin had published his utopian book Enquiry concerning Political Justice in 1793. A utopian work describes an ideal, perfect society. Malthus wrote about Godwin's ideas in several chapters. Godwin later responded with his own book, Of Population (1820).

The Marquis de Condorcet had also written about his hopeful vision for human progress in 1794. Malthus discussed Condorcet's work in his essay as well.

Malthus's book was a response to these very optimistic views. He argued that the natural difference between how fast population grows and how fast the Earth can produce food creates a huge problem. He felt this problem was too big to overcome for society to ever become perfect.

Malthus also mentioned other writers who influenced him, including Robert Wallace, Adam Smith, Richard Price, and David Hume. He said these authors were the main ones from whom he got the idea for his essay.

The first two chapters of the book explained Malthus's main idea: that food supply cannot keep up with population growth. The idea that population grows exponentially is now called the Malthusian growth model. Malthus used the terms geometric for population growth and arithmetic for food growth. These core ideas stayed the same in all future editions.

Other chapters in the first edition looked at different topics:

- Chapter 3 discussed how the Roman Empire was taken over by barbarians, partly due to population pressure. War was seen as a way to control population.

- Chapter 6 looked at the fast growth of new colonies, like the former Thirteen Colonies of the United States of America.

- Chapter 7 examined how things like diseases and famine act as checks on population.

- Chapters 18 and 19 explored how the problem of evil could be explained through natural theology. This idea suggests that the world is a process to "awaken matter" and that the "wants of the body" are needed to encourage effort and thinking. In this way, the principle of population would actually help God's overall plan.

The first edition of Malthus's book influenced other writers who studied natural theology, like William Paley and Thomas Chalmers.

Later Editions (2nd to 6th)

After his first book received both praise and criticism, Malthus changed his arguments and recognized other influences. He realized that many people had already thought about the problems of population growth and suggested solutions, even as far back as Plato and Aristotle. He also noted that more recently, French thinkers and British writers like Benjamin Franklin and Adam Smith had discussed the topic.

The second edition, published in 1803, was much larger and had a new title: "An Essay on the Principle of Population; or, a View of its Past and Present Effects on Human Happiness; with an enquiry into our Prospects respecting the Future Removal or Mitigation of the Evils which it occasions." Malthus was now clearly named as the author.

Malthus said the second edition could be thought of as a "new work." All the editions that followed (1806, 1807, 1817, and 1826) had only minor changes from this second edition.

The biggest change in the later editions was how the book was organized. Malthus added a lot more detailed evidence. For the first time, he looked at his Principle of Population region by region across the world population. The book was divided into four main parts:

- Book I – Looked at how population was controlled in less developed parts of the world and in the past.

- Book II – Examined how population was controlled in modern European countries.

- Book III – Discussed different systems or ideas that had been suggested to deal with the problems caused by population growth.

- Book IV – Explored future possibilities for reducing or lessening the problems from population growth.

Because of how important Malthus's work was, this new approach helped create the field of demography, which is the study of human populations. Some even see him as the founder of this field.

In the second edition, Malthus included a controversial passage. He wrote that a person born into a world where everything is already owned, who cannot get food from their parents and whose labor is not needed by society, has no right to any food. He said that "At nature's mighty feast there is no vacant cover for him." This passage caused a lot of strong negative reactions from critics. Malthus later removed it from future editions.

From the second edition onwards, in Book IV, Malthus suggested moral restraint as an additional way to control population. This meant people choosing to delay marriage or have fewer children.

Professor Robert M. Young noted that Malthus removed the chapters on natural theology from the second edition onwards. Also, the essay became less of a direct response to Godwin and Condorcet.

A Summary View

A Summary View on the Principle of Population was published in 1830. It was written by Rev. T.R. Malthus. Malthus wrote this shorter version for people who didn't have time to read the full book. He also wanted to "correct some of the wrong ideas" that people had about his main essay.

A Summary View ends with Malthus defending his Principle of Population. He argued against the idea that it made God seem unkind or went against the Bible.

Malthus died in 1834, and this shorter book was his final statement on the Principle of Population.

Other Books That Influenced Malthus

- Observations Concerning the Increase of Mankind, Peopling of Countries, etc. (1751) by Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790)

- Of the Populousness of Ancient Nations (1752) – David Hume (1711–76)

- A Dissertation on the Numbers of Mankind in Ancient and Modern Times (1753), Characteristics of the Present State of Great Britain (1758), and Various Prospects of Mankind, Nature and Providence (1761) – Robert Wallace (1697–1771)

- An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776) – Adam Smith (1723–90)

- Essay on the Population of England from the Revolution to Present Time (1780), Evidence for a Future Period in the State of Mankind, with the Means and Duty of Promoting it (1787) – Richard Price (1723–1791).

See Also

- Book of Murder – two satirical attacks on the Poor Law Amendment Act

- The dismal science

- Benjamin Franklin

- William Godwin

- David Hume

- Marquis de Condorcet

- Montesquieu

- Richard Price

- Adam Smith

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |