Anne Askew facts for kids

Anne Askew (born in 1521, died on July 16, 1546) was an English writer, poet, and Protestant preacher. She was found guilty of heresy during the time of Henry VIII, the King of England. Anne Askew and Margaret Cheyne are the only women known to have been both tortured in the Tower of London and then burned at the stake.

She is also one of the first known female poets to write in the English language.

Contents

Anne Askew's Early Life and Family

Anne Askew was born in 1521 in Lincolnshire, England. Her father, Sir William Askew, was a rich landowner and worked for King Henry VIII. Her mother was Elizabeth Wrotessley. Anne was the fourth of five children. She had two brothers, Francis and Edward, and two sisters, Martha and Jane. She also had two stepbrothers from her father's second marriage. Anne Askew was related to Robert Aske, who led a protest called the Pilgrimage of Grace.

Sir William Askew had planned for his oldest daughter, Martha, to marry Thomas Kyme. But when Martha died, Sir William decided that Anne, who was 15, should marry Thomas instead. This was to save money.

Anne's Strong Beliefs and Marriage

Anne was a very religious Protestant and stayed true to her faith her whole life. She read the Bible a lot, which made her believe that the idea of transubstantiation (the belief that bread and wine truly become the body and blood of Christ) was wrong. Her strong opinions caused problems in Lincoln. Her husband, Thomas Kyme, was a Catholic, and he did not like that Anne wanted to share her Protestant beliefs. Anne had two children with Kyme before he made her leave because of her religion. It is said that Anne wanted to divorce Kyme, so she was not too upset about leaving.

After leaving Kyme, Anne moved to London. There, she met other Protestants, like Anabaptist Joan Bocher, and continued to study the Bible. She went back to using her maiden name, Askew, after her marriage ended. In London, she kept on preaching her beliefs.

Arrests and Torture

In March 1545, Anne Askew was arrested by her husband, Thomas Kyme. She was taken back to Lincolnshire, where he told her to stay. But Anne escaped and went back to London to preach again. In early 1546, she was arrested once more but was later set free.

In May 1546, she was arrested for a third time. This time, she was taken to the Tower of London and tortured. She was one of only two women known to have been tortured there. Her torturers, Lord Chancellor Thomas Wriothesley and Sir Richard Rich, wanted her to name other women who shared her Protestant beliefs, but Anne refused. They used the rack, a device that stretched her body, but she would not give up her faith.

On June 18, 1546, Anne Askew was found guilty of heresy. She was sentenced to be burned at the stake.

Why Anne Askew Was Arrested

In the last year of King Henry VIII's rule, Anne Askew became part of a struggle in the royal court. There were two main groups: those who wanted to keep old religious traditions and those who wanted reforms. Stephen Gardiner, a traditionalist, told the king that stopping religious changes would help England make an alliance with the Catholic Emperor Charles V.

The traditionalist group tried to find people who would admit to being Protestants and then name others higher up, hoping to reach important people like Thomas Cranmer, the Archbishop of Canterbury. Anne Askew's brother, Edward, worked for Cranmer, which made her a target. The goal of her questioners might have been to involve Queen Catherine Parr herself. The Queen's ladies-in-waiting and close friends, who were thought to have Protestant beliefs, were also targets. These friends included Katherine Willoughby and the Queen's sister, Anne Parr.

Anne's "Plain Speaking"

In Anne's time, people like bishop Stephen Gardiner were suspicious of "plain speaking." They thought it was a trick the devil used to spread wrong ideas. Anne was seen as a dangerous example of this. Her smart answers showed she knew the Bible very well, sometimes even better than her questioners.

When bishop Edmund Bonner told her to "utter all things that burdened [her] conscience," she answered simply, using words from the Bible. She said, "God has given me the gifts of knowledge, but not of utterance." She also quoted a saying that "a woman of few words, is a gift of God."

Her answers made her questioners angry because they could not force her to say what they wanted. She kept saying that she believed "as the scripture does teach." This meant she would not accept any authority that was not from the Bible. When asked about the Eucharist (Communion), she asked, "If the host should fall and a beast did eat it, did the beast receive God or no?" She sometimes used traditional ideas about women to make fun of her questioners. She told them it was "against Saint Paul's learning that [she], being a woman, should interpret the scriptures, especially where so many wise men were."

Her questioners were very interested in her connection to the Holy Spirit. When asked if she acted with the Holy Spirit inside her, she answered, "If I had not, I was but a reprobate or cast away." Some groups, like the Anabaptists, were feared because they claimed to have the Holy Spirit's authority and rejected other laws.

Her Interrogation and Strength

Anne Askew was questioned two times before she was executed. On March 10, 1545, she was held under the Six Articles Act, a law against certain religious beliefs. She was questioned by the Bishop of London's chancellor, Edmund Bonner. He ordered her to be kept in prison for 12 days. During this time, she refused to confess anything. After 12 days, her cousin was allowed to visit and pay her bail.

On June 19, 1546, Anne Askew was put in prison again. She was questioned for two days by important officials like Chancellor Sir Thomas Wriothesley and Stephen Gardiner. They threatened her with death, but she still refused to confess or name other Protestants. Then, she was ordered to be tortured. Her torturers likely wanted her to say that Queen Catherine Parr was also a Protestant.

According to Anne's own writings, she was tortured only once. She was taken to a room in the White Tower. She saw the rack and was asked to name people who shared her beliefs. Anne refused. She was asked to take off her clothes except for her shift (a simple dress). Anne then got onto the rack, and her wrists and ankles were tied. Again, she was asked for names, but she said nothing. The wheel of the rack was turned, stretching her body. Anne wrote that she fainted from the pain. She was lowered and brought back to consciousness. This was done two more times.

Sir Anthony Knyvett, who was in charge of the Tower, refused to torture her anymore. He left the Tower and asked the king for a pardon, which the king gave him. But Wriothesley and Rich continued the torture themselves. They turned the handles so hard that Anne's shoulders and hips were pulled out of their sockets, and her elbows and knees were dislocated. Anne's screams could be heard outside the tower. Still, Anne gave no names. Her torture ended when Sir Anthony Knyvett ordered her to be returned to her cell.

Execution of Anne Askew

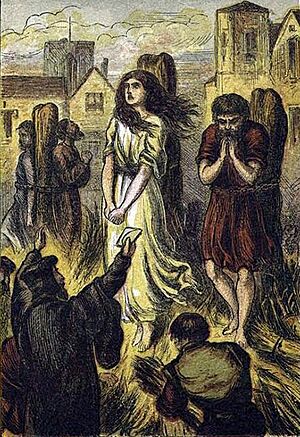

Anne Askew was burned at the stake in Smithfield, London, on July 16, 1546. She was 25 years old. Three other people were burned with her: John Lascelles, Nicholas Belenian, and John Adams. Because of the torture she had suffered, Anne could not walk. She had to be carried to the stake in a chair, wearing only her shift. She was pulled from the chair to the stake and tied upright with a chain around her middle. Some reports say that gunpowder was tied around the bodies of the four people to make their deaths quicker.

Before they died, the prisoners were offered one last chance to be pardoned. Bishop Shaxton stood in a pulpit and began to preach to them. Anne listened carefully. When he said something she thought was true, she agreed out loud. But when he said something that went against what she believed the Bible said, she called out, "There he misses, and speaks without the book."

Anne Askew's Legacy

Anne Askew wrote her own story of her arrests and trial. This account was published first by John Bale as The Examinations and later in John Foxe's Acts and Monuments in 1563. These books presented her as a Protestant martyr.

Her writings are special because they give a rare look into the life of a woman in the 1500s, especially her faith and how she stood up to male authority. She was very smart and knew English law well, trying to use it to her advantage. Even though her Examinations were changed a bit by Bale and Foxe, they are still a very important personal story from a time of great religious change.

See Also

- List of The Tudors episodes

Images for kids

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |