Battle of Breitenfeld (1631) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Breitenfeld |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Thirty Years' War | |||||||

Gustavus Adolphus at the battle of Breitenfeld, painting by J. J. Walther, 1632 painting in the Musée historique de Strasbourg. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 40 150

22 800 Swedes 17 350 Saxons 66 guns |

31 400

14 700 Imperials 15 700 Catholic League 1 000 Irregulars 27 guns |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 5 550

Sweden: 3 550 killed or wounded Saxony: 2 000 killed or wounded |

13 600

7 600 killed or wounded 6 000 captured 8 000 dead, deserted and captured over the following days |

||||||

The Battle of Breitenfeld was a major battle during the Thirty Years' War. It happened near Breitenfeld, about 8 kilometers (5 miles) northwest of Leipzig, Germany. On September 17, 1631, a combined army from Sweden and Saxony fought against the Imperial and Catholic League forces.

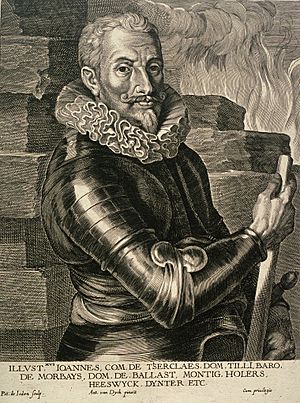

The Swedish-Saxon army was led by King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden and Elector John George I of Saxony. Their opponent was Generalfeldmarschall Johann Tserclaes, Count of Tilly. This battle was the first big victory for the Protestant side in the war.

Sweden joined the Thirty Years' War in 1628. King Gustavus Adolphus wanted to stop the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II from gaining too much power. He also wanted to protect Swedish lands near the Baltic Sea. In 1630, Gustavus Adolphus landed his army in Pomerania to help German Protestants.

In 1631, Field Marshal Tilly's army invaded Saxony. Elector John George I then decided to join forces with Gustavus Adolphus. Their combined armies had about 40,150 soldiers. Tilly's army had about 31,400 men. The two sides met near Breitenfeld.

During the battle, the Saxon army was pushed back by the Imperial cavalry. Tilly then tried to surround the Swedish army. But the Swedish troops were very flexible and had strong firepower. They quickly regrouped and counterattacked. Gustavus Adolphus led a large cavalry charge, forcing Tilly to retreat. Tilly's army lost about two-thirds of its soldiers.

This big victory allowed Gustavus Adolphus to march into southern Germany. It was his most famous military success. It also showed that his army used new tactics, like combining different types of soldiers and moving quickly. Other armies, including the Imperial army, soon started using these Swedish methods.

Contents

Understanding the Thirty Years' War

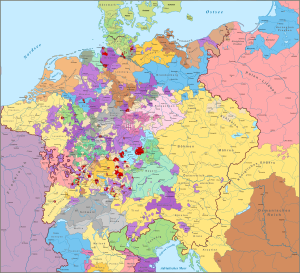

The Thirty Years' War was a series of conflicts in Europe from 1618 to 1648. It involved many different groups, mainly between Protestants and Catholics. The war started with a Protestant uprising in Bohemia in 1618.

Over time, the war grew bigger. It became a struggle between the major powers of Europe. For example, Catholic France ended up fighting against the Habsburgs and Catholic Spain. Sweden and Russia also had their own conflicts. Many German states and cities also joined the fight against Emperor Ferdinand II.

By 1629, the Imperial Army had defeated the Danish Army. This made the Emperor and the Catholic side much stronger. The Emperor then issued the Edict of Restitution. This law would have severely harmed the Protestant states. Because of this, King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden decided to step in and help the Protestants in Northern Germany.

Sweden Joins the War

Northern Germany was important to Sweden. If Catholic armies built a fleet in the Baltic Sea, it could threaten Sweden. Gustavus Adolphus first tried to find a peaceful solution. But talks with Emperor Ferdinand II failed in 1630. He also struggled to get Elector John George I of Saxony to join him.

In 1630, the Swedish King and his army of 13,200 men sailed from Sweden. They landed in Usedom on June 27, 1630. The Imperial forces there quickly retreated. The Swedes then captured Stettin, a key city in Pomerania. Through the Treaty of Stettin, the Duke of Pomerania had to help supply the Swedish army.

Gustavus Adolphus also got support from the dukes of Mecklenburg. They saw him as a liberator from Imperial control. By the end of 1630, Sweden had secured its position along the German Baltic Sea coast. The Swedish army also grew stronger by recruiting more soldiers.

Swedish Campaigns in Germany

At first, Gustavus Adolphus needed more support from German Protestant states. Many saw him as a foreign invader. Only a few, like William V, Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel and the city of Magdeburg, supported him. The Imperial and Catholic League armies, led by Generalfeldmarschall Johann Tserclaes, Count of Tilly, were still very strong.

After securing Pomerania, Gustavus Adolphus moved into Mecklenburg. He aimed to control river crossings over the Elbe. But his first attempts to capture key cities like Rostock failed. He then focused on the Oder river to the east.

By the end of 1630, the Swedish army had grown to over 100,000 men. Gustavus Adolphus divided his army into four groups. He led the largest group himself. In January 1631, he signed the Treaty of Bärwalde with France. This treaty gave Sweden money to keep a large army.

Capturing Frankfurt and Magdeburg's Fall

In February 1631, Gustavus Adolphus invaded Mecklenburg again. Tilly's army moved to stop him. Tilly captured the town of Neubrandenburg and treated its people harshly. Gustavus Adolphus avoided direct fights with Tilly. Instead, he captured Demmin and then moved towards Frankfurt an der Oder.

On April 13, 1631, Gustavus Adolphus's army attacked Frankfurt (Oder). After a fierce fight, the city was captured. Many of the city's defenders and citizens were killed. When Tilly heard about Frankfurt's fall, he rushed back to Magdeburg.

Magdeburg had been under siege by Imperial troops since April. The city's commander, Colonel Falkenberg, tried to hold out. But Tilly's army attacked the city's defenses. On May 19, Tilly decided to launch a final attack. On May 20, Imperial troops broke into Magdeburg.

The city was set on fire, and many people were killed. The Imperial troops looted the city for days. By May 24, Magdeburg was almost completely destroyed. Around 20,000 people died. This event shocked Europe and became a symbol of Imperial cruelty.

Battles Along the Elbe

The destruction of Magdeburg hurt Tilly's reputation. It also made Gustavus Adolphus change his strategy. He decided to seek revenge for the massacre. The Swedes used the story of Magdeburg to gain support for the Protestant cause across Europe.

Tilly marched from Magdeburg to face Gustavus Adolphus. He had about 30,000 men. Gustavus Adolphus built strong defenses along the Elbe, Havel, and Spree rivers. In July, Imperial General Pappenheim attacked Swedish positions near the Elbe. The Swedes quickly pushed him back.

Gustavus Adolphus gathered his army of 30,000 men. He fortified a camp at Werben. Tilly and Pappenheim combined their forces, totaling 20,000 men. They tried to attack the Swedish camp at Werben on August 6. But the Swedes' strong defenses and artillery fire forced them to retreat with heavy losses.

Preparing for Battle

The Saxon Elector, John George I, had tried to stay neutral. But Tilly's army invaded Saxony in June 1631 and began to besiege Leipzig. This forced John George I to act. On August 30, he finally allied with Gustavus Adolphus.

Their goal was to stop Tilly's siege of Leipzig. On September 15, the Swedish and Saxon armies met at Düben. Tilly's army had already captured Leipzig. Now, the two armies were only about 25 kilometers (15 miles) apart. Tilly could no longer avoid a fight. His army was also outnumbered.

Gustavus Adolphus felt confident because his army was larger. He had carefully avoided a direct fight with Tilly before. But now, he was ready. Tilly, on the other hand, wanted to wait for more troops. However, his generals, especially Pappenheim, pushed for an immediate attack. Pappenheim even tricked Tilly into moving his whole army forward.

On September 16, the Swedish and Saxon troops camped near Wölchau. The next morning, September 17, they marched towards Tilly's army. Tilly sent his cavalry to disrupt the Swedes as they crossed a swampy stream. This small fight led Tilly to prepare his army for battle on a ridge near Breitenfeld.

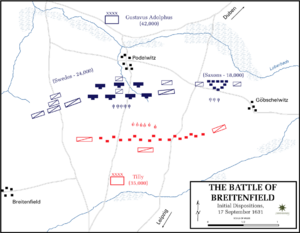

The Battlefield

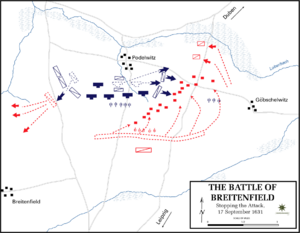

The battle took place on a gently sloping field about 10 kilometers (6 miles) north of Leipzig. Key villages around the field included Breitenfeld to the west, Seehausen to the east, Podelwitz to the north, and Wiederitzsch to the south. A marshy stream, the Lober, was behind Podelwitz.

The Swedish army was positioned south of Podelwitz. The Saxon army was to their left, between Zschölkau and Göbschelwitz. Tilly placed his artillery on the Galgenberg, a ridge between Breitenfeld and Seehausen. His army was lined up behind the ridge.

Troop Formations

The Swedish Army's Setup

The Swedish army had about 22,800 soldiers. They were placed on the far right of the allied line. They used a new formation with two lines, supported by reserve troops. This allowed for more flexibility and firepower.

The Swedish right wing had about 5,000 men, led by Gustavus Adolphus and General Johan Banér. It included cavalry and musketeers placed between cavalry units. The Swedish left wing had about 3,750 men, led by Field Marshal Gustav Horn. It also had infantry, cavalry, and dragoons.

The center of the Swedish army had about 14,650 men. It was made up of seven infantry brigades and three cavalry regiments. Colonel Lennart Torstensson commanded the artillery. He had four 24-pounder guns, eight 18-pounder guns, and 42 lighter regimental guns. These smaller guns were placed in front of each brigade.

The Saxon Army's Setup

The Saxon army had about 17,300 men. They were positioned to the left of the Swedish army. They used a more traditional formation, as they had not learned the new Swedish tactics. Elector John George I was the commander, with Field Marshal Hans Georg von Arnim as his second-in-command.

The Saxon center had nine infantry regiments. The left wing had six cavalry regiments, led by General Hans Rudolf von Bindauf. The right wing also had six cavalry regiments, led by Field Marshal Arnim. The Saxons also had 12 artillery pieces.

The Imperial-Catholic League Army's Setup

The Imperial-Catholic League army, led by Count of Tilly, had about 31,400 soldiers. They were spread out along a 3.5-kilometer (2-mile) front line. This army included Imperial soldiers, Catholic League soldiers, and some irregular troops.

The army had 27 artillery pieces. It also had 21,400 infantry, mostly in large formations called tercios. These were divided into four groups. The army also had 10,000 cavalry. Most of the soldiers were from German states, but some came from Spain, Wallonia, Italy, Croatia, and Hungary.

The Imperial-League right wing had 5,400 soldiers, led by General Egon von Fürstenberg. It included infantry and five cavalry regiments, plus 1,000 irregular Croatian and Hungarian cavalry. The left wing had 5,300 soldiers, led by Field Marshal Gottfried Heinrich zu Pappenheim. It included infantry, two harquebusier regiments, and five cuirassier regiments.

Tilly commanded the center, which had 18,700 troops. It was made up of twelve infantry regiments. Tilly also had a reserve of 2,000 men behind his center. The Imperial artillery was placed in front of the center.

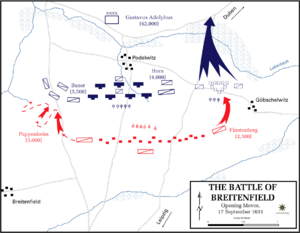

The Battle Begins

The battle started at noon with an artillery exchange. Tilly's cannons fired at the Saxon troops and the Swedish center and left wing. The Swedes and Saxons fired back. The Swedish artillery, especially Torstenson's heavy guns, were very effective. They fired three to five shots for every one Imperial shot.

Tilly's large tercios were easy targets for the Swedish guns. The Swedish troops, however, were spread out more and stood firm. During the two-hour cannon fire, about 1,000 Swedish soldiers and 1,000 Saxon soldiers were killed. The Imperial-League army lost about 2,000 soldiers.

Both sides stayed in place for a while. Tilly didn't want to leave his strong position on the Galgenberg ridge. The smoke from the cannons and dust from the troops blew into the Swedish soldiers' faces. To get the wind on their side, Gustavus Adolphus ordered his right wing to move to the left.

Pappenheim's Bold Attack

Without waiting for orders from Tilly, Pappenheim attacked the Swedish right wing at two o'clock. He tried to go around the Swedish guns. His goal was to break through Gustavus Adolphus's lines. But the Swedes were ready.

As Pappenheim's cavalry came close, Swedish musketeers fired a powerful volley at them. Then, Swedish cavalry fired their pistols. This surprising fire forced the Imperial cavalry to retreat. Pappenheim regrouped and attacked again.

The Swedish musketeers reloaded quickly. The Swedish cavalry charged, then fell back, letting the musketeers fire again. This happened every time Pappenheim tried to break through. Within an hour, Pappenheim made three frontal attacks, but all were pushed back.

Pappenheim then tried to go around the Swedish right flank. Gustavus Adolphus quickly sent reserves and units from the second line to strengthen his exposed side. Pappenheim made three more flanking attacks, but they were also pushed back. Many officers on both sides were killed. Pappenheim's cavalry was tired and losing morale.

Finally, Gustavus Adolphus ordered Banér to lead a large counter-charge. This attack broke Pappenheim's cavalry. Some fled to Tilly's artillery, while others retreated from the battlefield. Only one Imperial infantry regiment remained on this front. The Swedes attacked them with muskets and small cannons, destroying the regiment.

Tilly's Main Attack and Saxon Retreat

While Pappenheim attacked the Swedish right, Tilly's infantry stayed on the Galgenberg. Half an hour after Pappenheim's first charge, Imperial cavalry attacked the Saxon center and left wing. They quickly routed the Saxon Horse Guards. Other Saxon regiments fought bravely but were eventually broken.

At three o'clock, Tilly saw a chance to attack the Saxon army and the Swedish left flank. His infantry tercios marched down the Galgenberg, focusing on the Saxons. Other Imperial tercios pressed the Swedish center. Tilly's marching troops were hit hard by Torstenson's artillery.

Under pressure from Tilly's infantry and cavalry, most of the Saxon army panicked. By four o'clock, they were fleeing the battlefield. Even Elector John George was swept away in the retreat. Imperial cavalry captured the Saxon artillery and used it to fire at the fleeing Saxons and the Swedish left wing. Almost the entire Saxon army fled in just one hour. Only a few Saxon regiments remained, regrouping behind the Swedish left wing. The Protestant army had lost a third of its strength.

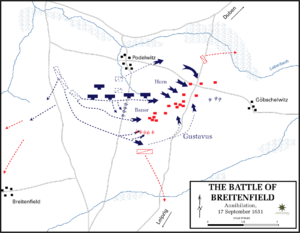

Swedish Regrouping and Counterattack

Tilly planned to surround Horn's open left flank. He ordered his cavalry to stop chasing the Saxons and attack the Swedish center from the side and rear. Tilly wanted to trap the Swedes against the Lober stream. As Tilly's large tercios moved, they kicked up huge clouds of dust and smoke. This made it hard to see.

Field Marshal Horn quickly saw what Tilly was doing. He ordered his left flank to turn sharply, forming a new defensive line at a 90-degree angle. This quick move took only 15 minutes. Horn used ditches along a country road as a defensive barrier. The smoke and dust helped hide his movements.

Tilly's cavalry tried to charge Horn's flank, but they were not well organized. Horn's musketeers fired a concentrated volley, pushing them back. Horn knew his thin lines couldn't hold against Tilly's large infantry attack alone. He used his cavalry to delay Tilly's advance and called for reinforcements. His fast-firing regimental artillery also fired grapeshot at the slow-moving Imperial infantry.

Horn reported his situation to Gustavus Adolphus. The King, after dealing with Pappenheim, learned that the Saxons had fled and Tilly was focusing on Horn. Gustavus Adolphus immediately ordered Colonel John Hepburn to bring his brigades and reserve units to help Horn. These troops quickly moved to Horn's left front, bringing their 18 regimental guns. Horn now had about 10,000 soldiers, and his line could not be surrounded.

Hepburn's Scottish musketeers, with the sun and wind behind them, fired powerful volleys and canister shots from their guns. This caused heavy losses for Tilly's advancing columns. Both sides fought fiercely. The smoke and dust made it hard to see, but Hepburn's musicians played Scottish marching music to keep his troops together. The constant firing from Horn's and Hepburn's musketeers and artillery forced the Imperial infantry to slow down and lose their momentum.

Tilly's Army Collapses

At five o'clock, Gustavus Adolphus saw a gap in Tilly's lines. He decided to launch a major counterattack. He rode to Banér on the right wing and ordered cavalry to charge Tilly's open left flank. This caused confusion among Tilly's tightly packed tercios.

The King then led his cavalry, including the famous Hakkapeliitta, in a flanking charge against the Imperial artillery. They rode up the slopes, killed the Imperial artillerymen, and captured their cannons. They then used these captured guns against Tilly's army.

Gustavus Adolphus ordered the rest of his right wing and center brigades to turn and occupy the Galgenberg. This cut off Tilly's retreat towards Leipzig. Torstenson moved his light artillery forward, and the Swedes recaptured the Saxon cannons. Now, Tilly's infantry was caught in a deadly artillery crossfire from all sides.

Between six and seven o'clock, Horn made his last cavalry charge. Hepburn's brigade led an infantry attack, supported by the Blue Brigade. These combined attacks, along with the devastating artillery fire, finally broke Tilly's army. The Imperial-League tercios suffered huge losses and lost all order.

Tilly himself was wounded by three musket bullets and hit twice in the head. He was saved and escorted to safety. Field Marshal Pappenheim tried to gather remaining cavalry, but most had fled. He protected Tilly's retreat. Scattered Imperial-League troops fled towards Leipzig, Merseburg, and Halle. The Swedish and Saxon cavalry chased them, capturing or killing many.

By sundown, the fighting stopped. Pappenheim retreated with the last Imperial-League soldiers under the cover of darkness. The exhausted Swedish infantry spent the night on the battlefield.

Battle Losses

Imperial-Catholic League Army Losses

The Imperial-League army suffered huge losses. Between 7,000 and 8,000 men were killed or wounded, and about 6,000 were captured. Tilly lost two-thirds of his army in just a few days. Many captured soldiers were later recruited into the Swedish army. Thousands more deserted or were killed by angry Saxon peasants.

Many important commanders were killed, including General of the Artillery Schönburg and General Erwitte. Field Marshals Tilly and Pappenheim were wounded. Tilly also lost all his artillery, his money, and 120 flags. These flags were taken to Riddarholmen Church in Stockholm as trophies.

Swedish-Saxon Army Losses

The Swedish army lost about 3,550 men. This included 2,100 infantry and 1,450 cavalry. Several colonels and a major general were killed.

The Saxons lost between 2,000 and 3,000 men. Most were killed by artillery fire or while fleeing. General Bindauf and Colonel Starschedel were among the dead.

What Happened Next

This was the first major defeat for the Catholic side in 13 years of war. Tilly's remaining army retreated south.

The Swedish victory at Breitenfeld sent shockwaves across Europe. It became a symbol of Protestant revenge for the Magdeburg massacre. Gustavus Adolphus could now choose where to go next. He decided that the Saxon troops would march towards Vienna, the capital of the Holy Roman Empire. The Swedes would move southwest towards the Rhine River to fight other Imperial troops.

Gustavus Adolphus's army marched southwest, facing little resistance. They captured cities like Erfurt, Würzburg, and Frankfurt am Main. They then reached the Rhine and captured Mainz, where they set up their winter camp.

The victory at Breitenfeld proved that Gustavus Adolphus's new military methods worked. It ensured that Sweden would stay in the war. This big loss forced the Emperor and other princes to rethink their war plans. Gustavus Adolphus's success encouraged more princes to join him. By the end of the month, Hanover, Hessia, Brandenburg, and Saxony were officially against the Empire. France also agreed to give more money to Sweden. Even though Gustavus Adolphus was killed a year later at the Battle of Lützen, the alliance remained strong, and the war continued.

Images for kids

See also

- Breitenfeld (1631) order of battle

- Hakkapeliitta

- Björneborgarnas marsch