Battle of Fishguard facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Fishguard |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the First Coalition | |||||||

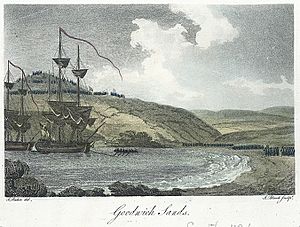

Goodwick sands French troops surrender to British forces James Baker, 18th century |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Light |

|

||||||

The Battle of Fishguard was a short military invasion of Great Britain by Revolutionary France. It happened during the War of the First Coalition. This quick event, from February 22 to 24, 1797, is famous. It was the last time a hostile foreign army landed on British soil. Because of this, it's often called the "last invasion of mainland Britain."

A French general named Lazare Hoche planned a three-part attack on Britain. This was to help a group called the Society of United Irishmen. Two smaller groups would land in Britain to distract the British. The main army would land in Ireland. Bad weather and poor discipline stopped two of these groups. But the third group, meant to land in Wales and march to Bristol, went ahead.

After some small fights with British forces and local people, the French commander, Colonel William Tate, had to give up. He surrendered completely on February 24. In a related sea battle, the British captured two of the French ships. These were a frigate and a corvette.

Contents

The French Invasion Plan

General Hoche wanted to land 15,000 French soldiers in Bantry Bay, Ireland. This was to support the United Irishmen. To draw away British soldiers, two smaller forces would land in Britain. One would go to northern England near Newcastle. The other would land in Wales.

In December 1796, Hoche's main group reached Bantry Bay. But terrible weather scattered his ships and weakened his force. He could not land any soldiers. So, Hoche decided to sail back to France. In January 1797, bad weather in the North Sea stopped the group heading for Newcastle. Also, some soldiers refused to obey orders. This force also returned to France. However, the third invasion went ahead. On February 16, 1797, four French warships left Brest. They were flying Russian flags to trick people. They were headed for Wales.

Who Were the Invaders?

The invasion force for Wales had 1,400 soldiers. They were part of a group called La Legion Noire. This was a special battalion led by Irish American Colonel William Tate. He had fought against the British in the American Revolutionary War. After a failed attempt to take over in New Orleans, he went to Paris in 1795. His soldiers were officially called the Seconde Légion des Francs. But they were known as the Légion Noire ("The Black Legion"). This was because they wore captured British uniforms dyed very dark brown or black. Many historians thought Tate was about 70 years old. But he was actually only 44.

The naval part of the mission was led by Commodore Jean-Joseph Castagnier. He had four warships, some of the newest in the French fleet. These were the frigates Vengeance and Résistance. The Résistance was on its first voyage. There was also the corvette Constance and a smaller lugger called the Vautour. The French government told Castagnier to land Colonel Tate's soldiers. Then he was to meet Hoche's group returning from Ireland to help them.

The Landing in Wales

Out of Tate's 1,400 soldiers, about 600 were regular French soldiers. Napoleon Bonaparte did not need them for his battles in Italy. The other 800 were irregular soldiers. This group included republicans, soldiers who had left their units, and some former prisoners. All of them had good weapons. Some of the officers were Irish. They landed at Carregwastad Point near Fishguard in Pembrokeshire on February 22. Some stories say they tried to enter Fishguard harbour first. But this idea probably came from a misunderstanding of an old pamphlet.

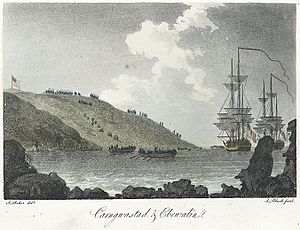

The Legion Noire landed in the dark at Carreg Wastad Point. This was three miles southwest of Fishguard. By 2 a.m. on February 23, the French had landed 17 boatloads of soldiers. They also brought 47 barrels of gunpowder, 50 tons of cartridges and grenades, and 2,000 guns. One rowing boat was lost in the waves. It carried several cannons and their ammunition.

First Actions on Land

The French soldiers moved inland and took over some nearby farmhouses. A group of French grenadiers led by Lieutenant St. Leger took Trehowel farm. This farm was on the Llanwnda Peninsula, about a mile from where they landed. Colonel Tate decided to set up his main camp here. The French soldiers were told to find their own food. But as soon as some of the irregular soldiers landed, they left the invasion force. They started to steal from local villages and small towns. One group broke into Llanwnda Church to get out of the cold. They started a fire inside using a Bible as kindling and church benches as firewood. However, the 600 regular soldiers stayed loyal to their officers.

On the British side, a commander named Knox planned to attack the French on February 23. This was if he was not greatly outnumbered. He sent out small groups to find out how strong the enemy was.

Avoiding a Big Battle

By the morning of February 23, the French had moved two miles inland. They took strong defensive spots on the high, rocky hills of Garnwnda and Carngelli. From there, they could see all around. Meanwhile, 100 of Knox's men had not yet arrived. He found out he was facing a force nearly ten times bigger than his own. Many local people were running away in fear. But many more were coming into Fishguard. They had all sorts of homemade weapons. They were ready to fight with the local Volunteer Infantry. Knox had three choices: attack the French, defend Fishguard, or go back towards soldiers coming from Haverfordwest. He quickly decided to retreat. He ordered his men to disable the nine cannons in Fishguard Fort. But the gunners from Woolwich refused to do it. At 9 a.m., Knox started to move back. He kept sending out scouts to check on the French. Knox and his 194 men met the extra soldiers led by Lord Cawdor at 1:30 p.m. This was at Treffgarne, eight miles south of Fishguard. After a quick disagreement about who was in charge, Cawdor took command. He led the combined British forces towards Fishguard.

By now, Tate was having serious problems. Discipline among his irregular soldiers had broken down. They had found a supply of wine from a Portuguese ship that had crashed on the coast weeks before. Overall, spirits were low. The invasion was losing its energy. Many irregular soldiers rebelled against their officers. Many others had simply disappeared during the night. The only soldiers left were the French regulars, including his Grenadiers. The Welsh people had not welcomed Tate's invaders. Instead, they were hostile. At least six Welsh and French people had already died in clashes. Tate's Irish and French officers advised him to surrender. Castagnier had left with the ships that morning. This meant there was no way to escape.

By 5 p.m., the British forces had reached Fishguard. Cawdor decided to attack before dark. His 600 men dragged their three cannons behind them. They marched up narrow Trefwrgi Lane from Goodwick towards the French position on Garngelli. Cawdor did not know that Lieutenant St. Leger and the French Grenadiers had come down from Garngelli. They had prepared an ambush behind the high hedges of the lane. But before it could happen, Cawdor called off his attack. He returned to Fishguard because it was getting dark.

The French Surrender

That evening, two French officers arrived at the Royal Oak pub. Cawdor had set up his headquarters there on Fishguard Square. They wanted to talk about surrendering with some conditions. Cawdor bluffed and said that with his stronger force, he would only accept a complete surrender. He gave Colonel Tate an ultimatum: he had until 10 a.m. on February 24 to surrender on Goodwick Sands. If not, the French would be attacked. The next morning, the British forces lined up ready for battle on Goodwick Sands. Up on the cliffs above them, the townspeople came to watch. They waited for Tate's answer. The local people on the cliff included women wearing traditional Welsh costume. This included a red whittle (shawl) and a Welsh hat. From a distance, some of the French soldiers thought these looked like red coats and shako hats. They believed they were regular British soldiers.

Tate tried to delay, but he finally accepted the terms of the complete surrender. At 2 p.m., the sounds of French drums could be heard. They led the column down to Goodwick. The French piled up their weapons. By 4 p.m., the French prisoners were marched through Fishguard. They were taken to a temporary prison at Haverfordwest. Meanwhile, Cawdor rode with some of his Pembroke Yeomanry Cavalry to Trehowel farm. He went to officially receive Tate's surrender. Sadly, the actual document has been lost.

After a short time in prison, Tate was sent back to France in a prisoner exchange in 1798. Most of his invasion force also returned.

A Local Heroine

A famous local heroine, Jemima Nicholas, is said to have tricked the French invaders. She told local women to dress in cloaks and tall black hats that looked like soldiers' hats. The British commander gathered them. They marched up and down a hill until dusk. This made the French commander think his soldiers were outnumbered. Nicholas is also said to have captured twelve French soldiers by herself. She then took them to town and locked them inside St. Mary's church.

On March 9, 1797, HMS St Fiorenzo, commanded by Sir Harry Neale, was sailing with Captain John Cooke's HMS Nymphe. They met La Resistance, which had been damaged by bad weather while going to Ireland. They also found La Constance. Cooke and Neale chased them. They fought for half an hour. After that, both French ships surrendered. There were no injuries or damage on the British ships. The two French ships lost 18 killed and 15 wounded. La Resistance was repaired and renamed HMS Fisgard. La Constance became HMS Constance. Castagnier, on board Le Vengeance, made it safely back to France.

Legacy of the Invasion

Money Matters

When news of the invasion reached London a few days later, people rushed to the Bank of England. They wanted to exchange their paper money for gold. This was a right at the time. However, the bank did not have enough gold for all the paper money. So, on February 27, 1797, Parliament passed a law. This law stopped people from exchanging banknotes for gold until 1821. This event, triggered by the Battle of Fishguard, was important. It was the first time that paper money from a central bank could not be exchanged for gold. This changed how banknotes are used even today.

A Special Honour

In 1853, people worried about another French invasion. Lord Palmerston gave the Pembroke Yeomanry a special honour called "Fishguard". This military unit still exists today. It is the only unit in the British Army to have a battle honour for a fight on the British mainland. It was also the first battle honour given to a volunteer group.

Another French Attack

In August of the next year, another French force landed in County Mayo, Connacht, in western Ireland. Like the event at Fishguard, this mission also failed. The French surrendered at the Battle of Ballinamuck.

Memorial Tapestry

In 1997, a 100-foot-long Last Invasion Tapestry was made. Seventy-eight volunteers sewed it. It was created to mark 200 years since the events.

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |