Siege of Havana facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Siege of Havana |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Anglo-Spanish War (1762–63) | |||||||

The Capture of Havana, 1762, Taking the Town, 14 August, Dominic Serres |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 31,000 23 ships of the line 11 frigates 4 sloops 3 bomb ketches 1 cutter 160 transport ships |

11,670 10 ships of the line 2 frigates 2 sloops 100 merchant ships |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 5,366 killed, wounded, captured, missing, sick, or died of disease 1 ship of line scuttled 2 ships of the line sunk |

11,670 killed, wounded, captured, missing, sick, or died of disease 10 ships of the line captured 2 frigates captured 2 sloops captured 100 merchant ships captured |

||||||

The Siege of Havana was a big battle where the British attacked and took control of Havana, a city ruled by Spain. This happened from March to August 1762. It was part of a larger conflict called the Seven Years' War.

Spain had tried to stay neutral in the war. But then, Spain signed an agreement with France called the "Family Compact." This made Britain declare war on Spain in January 1762.

The British government decided to attack Havana. Havana was a very important Spanish fortress and a naval base. Taking it would make Spain weaker in the Caribbean. It would also make Britain's own colonies in North America safer.

A large British naval force, with ships from Britain and the West Indies, sailed towards Havana. They also carried many British and American soldiers. They surprised the Spanish by approaching from an unexpected direction. This allowed them to trap the Spanish fleet in Havana harbor and land their troops easily.

The Spanish leaders decided to try and delay the British attack. They hoped that the strong defenses of the city, along with tropical diseases and the start of hurricane season, would weaken the British forces. However, the main fortress, Morro Castle, was on a hill that the Spanish governor had not fortified. The British set up cannons there and bombed the fortress every day.

Morro Castle eventually fell after its commander, Luis Vicente de Velasco, was badly wounded. After Morro Castle was captured, the rest of the city's defenses also fell. Havana, its soldiers, and the Spanish ships in the harbor surrendered before the hurricane season fully began.

The British military leaders received large rewards for their victory. The Spanish governor and admiral were put on trial when they returned to Spain. They were punished for not defending the city better and for letting the Spanish fleet be captured. Havana stayed under British control until February 1763. It was then given back to Spain as part of the Treaty of Paris, which officially ended the war.

Contents

The Siege of Havana

Why Havana Was Important

Havana was a very important port and naval base in the late 1700s. It was also the strongest fortress in Spanish America. It had a royal shipyard where large warships could be built. Spain saw it as its most important naval shipyard.

There had been plans to attack Havana before, but none had succeeded. Its strong defenses made Spanish commanders believe it was almost impossible to capture. They thought it could not be starved into surrender because it had enough food for its people.

Britain had been at war with France since May 1756. But Spain, led by King Ferdinand VI, stayed neutral. After Ferdinand died in 1759, his half-brother, Charles III, changed this policy. He signed a treaty with France in 1761, creating the "Family Compact." This agreement meant France and Spain would work together against Britain.

In December 1761, Spain stopped British trade. They seized British goods and kicked out British merchants. Because of this, Britain declared war on Spain in January 1762.

Spain Gets Ready

Before Spain joined the war, King Charles III prepared to defend his colonies. For Cuba, he appointed Juan de Prado as the Captain General of Cuba. This was an administrative job, not a military one. De Prado arrived in Havana in February 1761 and started to improve the city's defenses. However, the work was not finished when the British attacked.

In June 1761, seven warships led by Admiral Gutierre de Hevia arrived in Havana. They brought two infantry regiments, adding 996 soldiers to the Havana garrison. This brought the total to 2,400 regular soldiers. There were also 6,300 sailors and marines on the ships.

However, by the time the siege began, many soldiers were sick with yellow fever. The effective defending forces were about 1,900 regular soldiers, 750 marines, about 5,000 sailors, and 2,000 to 3,000 local soldiers (militia). Many more people had no weapons or training.

The main soldiers defending Havana included:

- España Infantry Regiment (481 men)

- Aragón Infantry Regiment (265 men)

- Havana Infantry Regiment (856 men)

- Edinburgh's Dragoons (150 men)

- Army gunners (104 men)

- Navy gunners and marines (750 men)

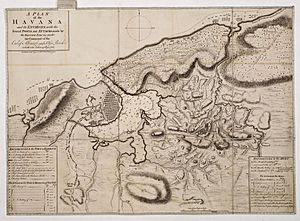

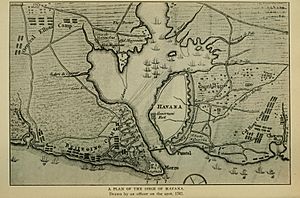

Havana had one of the best natural harbors in the West Indies. Its entrance channel was 180 meters wide and 800 meters long. Two strong fortresses guarded this entrance. On the north side was the very strong Castillo de los Tres Reyes del Morro, known as Morro Castle. It had 64 cannons and 700 men. Most of its guns faced Havana's port and bay. It was also overlooked by an unfortified hill called La Cabana. Although there were plans to fortify La Cabana, no cannons had been placed there when the siege started.

On the south side, the older Castillo de San Salvador de la Punta defended the channel. A strong chain could also be stretched across the channel from El Morro to La Punta to block ships. Havana itself was on the south side of the channel and had a wall about 5 kilometers long.

Britain Plans the Attack

Two days after declaring war on Spain, the British government chose Havana as a main target. They believed losing Havana would greatly weaken Spain in the Caribbean. They made detailed plans for a combined attack by sea and land.

Vice-Admiral Sir George Pocock was to lead the naval force. He would transport soldiers under George Keppel, 3rd Earl of Albemarle to the West Indies. There, they would join another naval squadron. They would also pick up more troops from Martinique and 4,000 men from British colonies in North America. The plan was to keep their final destination a secret until the attack.

These plans changed a bit. Martinique was captured before Pocock sailed. Also, 3,000 British and American troops from New York arrived late. A plan to bring 2,000 slaves from Jamaica to help with construction only resulted in 600. Many slave owners did not want to let them go.

In February, British troops got ready. These included:

- 22nd Regiment of Foot

- 34th Regiment of Foot

- 56th Regiment of Foot

- 72nd Richmond's Regiment of Foot

On March 5, the British expedition sailed from England. It had 7 warships and 4,365 men on 64 transport ships. They arrived in Barbados on April 20. Five days later, they reached Fort Royal on Martinique. There, they picked up 8,461 more men. Rear Admiral Rodney's squadron, with 8 warships, also joined them. This made a total of 15 warships.

On May 23, the expedition was further strengthened by another squadron from Port Royal, Jamaica. The combined force now had 21 warships, 24 smaller warships, and 168 other ships. They carried about 14,000 sailors and marines, plus 3,000 hired sailors and 12,826 regular soldiers.

The Battle Begins

The usual way to reach Havana from the north was long and slow. Ships would sail west, then around the western tip of Cuba, and then east against the wind. This would take weeks, giving Havana plenty of warning.

However, the British found a different way. To the north of Havana, there is a wide area of shallow water, reefs, and small islands. Only small boats could usually pass through, except for one deep channel called the Old Bahama Channel. This channel was only about 10 miles wide at its narrowest. Spanish sailors thought it was too dangerous for large warships. But a British frigate surveyed it. Its captain left men on the small islands to mark the channel's edges. This allowed the entire British fleet to pass through safely and without being seen.

On June 6, the British force appeared near Havana. Immediately, 12 British warships blocked the entrance to the harbor. After looking at the city's defenses, the British planned to attack Morro fortress first. They would use a formal siege style, like those designed by Vauban. They believed that capturing Morro would force the Spanish to surrender the city. However, their first look had underestimated how strong Morro fortress was. It was on a rocky point where it was hard to dig trenches. A large ditch cut into the rock protected the fort from the land side.

Prado had heard about British ships two days before they arrived. But he did not believe large warships could use the Old Bahama Channel. Prado and Admiral Hevia were surprised by the size of the British force. They decided to try and delay the attack. Prado sent messages to the French in Saint-Domingue and to Spain, asking for help. He also asked for soldiers from Santiago de Cuba. Two relief forces started from there in July, but they were delayed by lack of food and sickness. One turned back, and the other was still a day's march from Havana when the city surrendered.

Besides hoping for help, Prado and his soldiers had some advantages. The hurricane season would start in late August, which could endanger the British fleet. The wet weather would also likely cause yellow fever among the British soldiers. Prado had 1,500 Spanish regular soldiers and about 2,300 local soldiers, plus sailors from the fleet.

There were 12 Spanish warships in the harbor, plus two new ones that were not yet manned. There were also smaller warships and about 100 merchant ships. The many merchant ships made the Spanish leaders decide not to send their fleet out to fight the British landings. This also followed Admiral Hevia's orders to protect Cuba's trade. The fleet's gunners and marines were sent to defend Morro and Punta fortresses. Most of the fleet's cannonballs, gunpowder, and best guns were also moved to these two fortresses. Regular soldiers were assigned to defend the city itself. Prado also ordered all women, children, and sick people to leave the city. Only men able to fight remained.

The channel entrance was immediately closed with a large chain. Also, three warships (Asia, Europa, and Neptuno) were sunk behind the chain. This trapped the remaining Spanish warships in the harbor. But they were already outnumbered by the British fleet. This move also made more sailors available to defend the city. The Spanish leaders knew how important Morro was, so they made its defense their top priority.

The next day, British troops landed northeast of Havana. They began moving west. They met some local soldiers, who were easily pushed back. By the end of the day, British soldiers were near Havana. The defense of Morro was given to Luis Vicente de Velasco e Isla, a naval officer. He immediately prepared the fortress for a siege.

Attacking Morro Castle

On June 11, a British group attacked a small fort on the La Cabana heights. Only then did the British realize how strong Morro was. It was surrounded by thick bushes and protected by a large ditch. When their siege equipment arrived the next day, the British began building gun positions among the trees on La Cabana hill. This hill overlooked Morro (it was about 7 meters higher) as well as the city and the bay. Surprisingly, the Spanish army had left this hill undefended, even though its importance was well known. King Charles III of Spain had told Prado earlier to fortify this hill, calling it the most urgent task. The work had started, but no cannons had been placed there.

Two days later, a British group landed at Torreón de la Chorrera, on the west side of the harbor. Meanwhile, Colonel Patrick Mackellar, an engineer, was in charge of building the siege works against Morro. Since digging trenches was impossible, he decided to build walls of earth instead. He planned to dig a tunnel towards a part of Morro once his siege works reached the ditch. He would then create a path across this ditch using the dirt from his tunnel.

By June 22, four British gun positions with twelve heavy cannons and 38 mortars began firing on Morro from La Cabana. Mackellar slowly moved his earthworks closer to the ditch, protected by these cannons. By the end of the month, the British were hitting Morro directly up to 500 times a day. Velasco was losing as many as 30 men daily. Repairing the fortress every night was so tiring that men had to be rotated into the fort from the city every three days. Velasco finally convinced Prado that a surprise attack on the British cannons was needed. At dawn on June 29, 988 men (a mix of grenadiers, marines, engineers, and slaves) attacked the siege works. They reached the British cannons from behind and started to disable them. But the British reacted quickly, and the attackers were pushed back before they could do serious damage.

On July 1, the British launched a combined attack by land and sea on Morro. Four warships were sent for this: HMS Stirling Castle, HMS Dragon, HMS Marlborough and HMS Cambridge. The naval and land cannons fired on Morro at the same time. However, the naval cannons were not effective because the fort was too high up. Counter-fire from thirty of Morro's cannons caused 192 casualties and badly damaged the ships. One ship was later sunk, forcing them to leave. Meanwhile, the land cannons were much more effective. By the end of the day, only three Spanish cannons were still working on the side of Morro facing the British.

The next day, however, the British earthworks around Morro caught fire. The gun positions burned down, destroying much of the work done since mid-June. Velasco immediately took advantage of this. He re-mounted many cannons and repaired the damage to Morro's defenses.

Since arriving in Havana, the British army had suffered greatly from malaria and yellow fever. Their strength was now cut in half. Since the hurricane season was coming, Albemarle was in a race against time. He ordered the gun positions to be rebuilt with help from the fleet's men. Many 32-pounder cannons were taken from the lower decks of several ships to equip these new positions.

By July 17, the new British gun positions had slowly silenced most of Velasco's cannons. Only two were still working. Without cannon cover, it became impossible for the Spanish soldiers to repair the damage being done to Morro. Mackellar was also able to continue building siege works to get closer to the fortress.

Because the army was in such bad shape, work was slow. All hope for the British army now depended on reinforcements arriving from North America.

Over the next few days, the siege works progressed enough for the British to start digging a tunnel towards the right side of Morro. Meanwhile, the British cannons, now unopposed, were hitting Morro up to 600 times daily. This caused about sixty casualties. Velasco's only hope was to destroy the British siege works. So, on July 22, 1,300 regular soldiers, sailors, and local militia attacked the siege works around Morro in three groups. The British pushed back the Spanish attack. The Spanish retreated, and the siege works were left mostly intact.

On July 24, Albemarle offered Velasco a chance to surrender. He even let Velasco write his own terms for giving up. Velasco replied that the issue would be decided by fighting. Three days later, the reinforcements from North America, led by Colonel Burton, finally arrived. These reinforcements had been attacked by the French on their journey, losing about 500 men. They included:

- 46th Thomas Murray's Regiment of Foot

- 58th Anstruther's Regiment of Foot

- American provincials (3,000 men)

- Gorham's and Danks' Rangers – combined into a 253-man ranger corps.

By July 25, 5,000 soldiers and 3,000 sailors were sick.

On July 29, the tunnel near the right side of Morro fort was finished and ready to explode. Albemarle pretended to launch an attack, hoping Velasco would finally surrender. Instead, Velasco decided to launch a desperate attack from the sea on the British miners in the ditch. At 2:00 am the next day, two Spanish schooners attacked the miners from the sea. Their attack failed, and they had to retreat. At 1:00 pm, the British finally blew up the tunnel. The explosion's debris partly filled the ditch. Albemarle thought it was passable and launched an assault. He sent 699 chosen men against the right side of the fort. Before the Spanish could react, sixteen men got a foothold on the fort. Velasco rushed to the breach with his troops. He was badly wounded during the hand-to-hand fighting. The Spanish troops fell back, leaving the British in control of Morro fort. Velasco was taken back to Havana, but he died of his wounds by July 31.

The British then took a position that overlooked the city of Havana and the bay. Cannons were brought up along the north side of the entrance channel, from Morro fort to La Cabana hill. From there, they could fire directly on the town.

Havana Gives Up

On August 11, Prado rejected Albemarle's demand for surrender. So, the British cannons opened fire on Havana. A total of 47 cannons (15 large, 32 smaller), 10 mortars, and 5 howitzers pounded the city from 500–800 meters away. By the end of the day, Fort la Punta was silenced. Prado had no choice but to surrender.

The next day, Prado was told there was only enough ammunition for a few more days. He made late plans to move the gold and silver from Havana to another part of the island. But the city was surrounded. Talks about the surrender terms for the city and the fleet continued. Prado and his army were allowed to leave with military honors on August 13. Hevia did not burn his fleet, so it fell completely into British hands.

The British lost many men attacking Havana. This ended any chance of attacking Louisiana. The French took advantage of so many British troops being moved from Canada. They captured Newfoundland with a small force. Newfoundland was later recaptured in the Battle of Signal Hill on September 15, 1762.

What Happened After the Siege

On August 14, the British entered the city. They now controlled the most important harbor in the Spanish West Indies. They also took military equipment, over 1.8 million Spanish pesos, and goods worth about 1 million Spanish pesos. They captured nine warships in Havana harbor, which was a big part of the Spanish Navy. These included Aquilón, Conquistador, Reina, San Antonio, Tigre, San Jenaro, América, Infante, and Soberano. They also took a 78-gun ship and about 100 merchant ships. Two new warships, San Carlos and Santiago, that were almost finished in the dockyard, were burned. In addition, two small frigates and two 18-gun sloops, including the Marte, were captured.

After the capture, the naval commander Pocock and military commander Albemarle each received large payments of prize money. Commodore Keppel, the naval second-in-command, received a smaller amount. Each of the 42 naval captains present received £1,600. The military second-in-command, Lieutenant-General Eliott, received the same as Commodore Keppel. He used his money to buy a large estate. Regular soldiers received just over £4, and ordinary sailors received a bit less.

During the siege, the British lost 2,764 men killed, wounded, captured, or deserted. But by October 18, another 4,708 had died from sickness. One of the brigades that lost the most men was sent to North America. It lost another 360 men within a month of arriving there. Three British warships were lost either directly from Spanish gunfire or from severe damage. Shortly after the siege, HMS Stirling Castle was too damaged to use and was sunk. HMS Marlborough sank in the Atlantic due to damage. HMS Temple was lost while returning to Britain for repairs.

King Charles III of Spain set up a group of generals to try Prado and others for losing Havana. Prado, Hevia, and nine other officials were accused of treason. Their trial looked at their actions during Prado's time as governor and their decisions during the siege. The group blamed Prado and Hevia the most. They said these leaders failed to fortify the Cabana hill properly and gave it up too easily. They also said they crippled the Spanish fleet by sinking ships that stopped the others from fighting. They also surrendered the ships instead of burning them. They did not launch any major counterattacks. Finally, they did not move the royal treasury before surrendering. After a long trial, Prado was found guilty and sentenced to death, but his sentence was changed, and he died in prison. Hevia was sentenced to 10 years of house arrest and lost his job, but he was later pardoned and given his job back.

Velasco's family was honored, and his son was given a special title. King Charles III ordered that there should always be a ship named Velasco in the Spanish fleet. Losing Havana and Western Cuba was a big blow to Spain. They lost a lot of money and, even more, their reputation. This defeat, along with the British capture of Manila a month and a half later, meant Spain lost its "Key to the New World." These events showed that Britain had strong naval power and that the Spanish Empire was not as strong as it seemed.

The Spanish leaders realized their regular army in Cuba was not strong enough to fight the British army in America. So, they decided to create a trained local army (militia). This militia would have good weapons and training, led by experienced officers. The regular army of about 3,200 men would be supported by a trained militia of 7,500 soldiers. Many of the officers would come from important Cuban families.

Havana and Manila were given back to Spain because of the Treaty of Paris signed in February 1763. But the British stayed in Havana for two more months. Then, a new Captain General of Cuba, Alejandro O'Reilly, arrived to bring back Spanish rule. Spain agreed to give Florida and Menorca to Great Britain. Losing Florida and accepting British control of the Mosquito Coast made Cuba even more important as a defense for Spain's South American colonies. Spain received French Louisiana as payment for helping France in the war and to make up for losing Florida.

Pictures from the Siege

Numerous paintings and drawings of the battle were made, notably by Dominic Serres:

-

Bombardment of the Morro Castle (Rafael Monleón)

See Also

In Spanish: Toma de La Habana para niños

In Spanish: Toma de La Habana para niños

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |