Battle of Pontvallain facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Pontvallain |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Hundred Years' War | |||||||

The Battle of Pontvallain, from an illuminated manuscript of Froissart's Chronicles |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| France | England | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Bertrand Du Guesclin Louis de Sancerre |

Robert Knolles Thomas Grandison Walter Fitzwalter John Minsterworth |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 5,200 | 4,000–6,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Light | Most of the English army | ||||||

The Battle of Pontvallain was an important fight during the Hundred Years' War. It happened in north-west France on December 4, 1370. A French army, led by Bertrand du Guesclin, strongly defeated an English force. This English group had separated from a larger army commanded by Sir Robert Knolles. The French had about 5,200 soldiers, while the English force was roughly the same size.

The English army had been moving across northern France, burning and stealing from towns. As winter approached, the English leaders argued and split their army into four parts. The Battle of Pontvallain actually involved two separate fights. In the first, Guesclin, who had just become the top French military leader (called the constable of France), surprised a large part of the English army at Pontvallain. His soldiers had marched all night to get there. They completely wiped out the English force.

At the same time, Guesclin's helper, Louis de Sancerre, attacked a smaller English group near Vaas. This group was also destroyed. Sometimes, these two fights are called separate battles. After these victories, the French chased the remaining English soldiers for months. They took back much of the land they had lost. Even though these battles were not huge, they were very important. The English were completely defeated, which ended their reputation for being unbeatable in open battles. This reputation had lasted since the war began in 1337.

Contents

Why the War Started Again

The Hundred Years' War began in 1337. It was a long conflict between the kings of England and France. It started because of disagreements between Philip VI of France and Edward III of England. Edward III held lands in France, but Philip VI said Edward was not following his duties as a vassal (a lord who owes loyalty to a king). So, Philip decided to take back those lands.

In 1340, Edward III claimed he should be the King of France. He said he was the rightful heir through his mother. For many years, the English army won many battles against larger French forces. In 1356, the French army was badly beaten at the Battle of Poitiers. King John II of France was even captured. This led to a peace agreement called the Treaty of Brétigny in 1360.

This treaty gave large parts of south-west France to England. Edward III gave up his claim to the French throne. The treaty was supposed to fix the problems that caused so much fighting. It would give England more control over its lands in France, especially Aquitaine and Poitou. But the French people were very unhappy with this deal.

In 1369, Charles V of France, King John's son, declared war again. He said Edward III had not followed the treaty's rules. French forces immediately started trying to take back castles. English commanders who had fought before were called back. But things went badly for England from the start. Two important English leaders were killed. The French gained a lot of land in the west, including the city of Poitiers.

French Battle Plan

The war changed a lot after 1369. This new period is sometimes called the Carolinian phase. The French were much better prepared and immediately went on the attack. King Charles V had more money and soldiers than England. Edward III was getting old and sick, and his son, Edward the Black Prince, was also ill. France also had more people and more wealth than England. The French also used new technology, like better armor for their horses.

Most of the fighting happened in Aquitaine, which was a large English territory in France. This meant the English had very long borders to defend. Small French groups could easily sneak in and cause trouble. The French used a smart strategy: they avoided big, open battles. Instead, they wore down the English by attacking small, scattered groups. This was an offensive war for France, and England was not ready for it.

English Battle Plan

|

The 1370 campaign was part of a multi-faceted offensive by the English (in red), with Knolles marching west from Calais (although being turned away from Normandy and Burgundy); and the Black Prince and the Earl of Pembroke occupying Aquitaine and attacking Poitou, further west. The French (in blue), led by Guesclin, marched south to intercept Knolles.

Knolles's campaign route through northern France, August–September 1370, and his proximity to both Pontvallain and Derval.

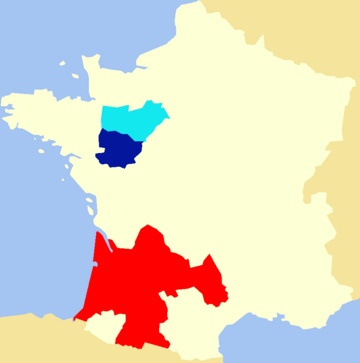

Theatres of war in 1370: The English-controlled Duchy of Aquitaine (in red), and the French counties of Anjou (in dark blue) and Maine (in light blue).

|

The English planned to use two armies. One army would fight in Aquitaine, in south-west France. It was supposed to be led by the experienced Black Prince. This army would try to take back lands the French had recently captured. However, the Black Prince was so sick he had to be carried on a stretcher. He could not lead the army himself, so he had to let others take charge.

The other English army would start from Calais, an English area in northern France. This northern army was to be led by Sir Robert Knolles. He was a very experienced soldier. Knolles signed a contract to lead the army. But the King and his advisors knew there might be problems. Knolles was not as high-ranking as some of the other commanders. To stop the army from splitting up, the captains had to sign a contract. They promised to work together and not let disagreements divide them.

Leading Up to the Battle

English Army's Journey

Knolles landed at Calais in August 1370 with 4,000 to 6,000 mounted soldiers. He waited for orders, but none came. So, he began a long journey through northern France, raiding and stealing. This was a common English tactic called a chevauchée. It meant a large-scale raid on horseback. The goal was to destroy as much as possible and force the French army to come out and fight a big battle.

Knolles's army marched through the Somme region. They showed their strength outside Reims and then moved towards Paris. As they marched, they captured many towns. If the French refused to pay money, the English would burn the towns. Knolles reached Paris on September 24. But the city was well-protected, and the French soldiers stayed inside. Knolles tried to make them come out and fight, but they refused.

By October, Knolles had moved south. He captured castles and monasteries. He wanted to be ready to march into Poitou or southern Normandy. This would let him help the Black Prince or get a new base. But many of his commanders, who thought they were more important than Knolles, were unhappy. They thought he wasn't brave enough. Sir John Minsterworth, a knight from Wales, even made fun of Knolles.

English Army Splits Up

The English system of shared leadership caused problems. The commanders argued about how to share the stolen goods and ransom money. In November 1370, they argued about where to spend the winter. Knolles knew the French were getting closer. He wanted to move west into Brittany to avoid a surprise attack. But his captains disagreed. They wanted to stay and keep raiding the countryside. They believed they could beat any French attack. They needed to keep raiding because the government had only paid them for a short time. They had to get their own money from the land.

Knolles threatened to leave, and when the others refused to join him, he left. He took the largest group of soldiers with him, along with a lot of treasure. With Knolles gone, the remaining 4,000 English soldiers split into three groups. One was led by Thomas Grandison, another by Walter Fitzwalter, and the third by John Minsterworth. These groups went their separate ways to find more supplies and loot.

By the evening of December 3, Knolles was far to the west. Grandison's group of 600 to 1,200 soldiers was spread out near Pontvallain. Fitzwalter was several miles to the south. The location of Minsterworth's group is not known.

French Army's Movements

Bertrand du Guesclin was made the top military commander of France on October 2. King Charles V chose him because Guesclin was good at leading small groups and fighting in unexpected ways. This fit the French plan to wear down the English. On October 24, Guesclin made a special agreement with Olivier de Clisson, another experienced commander. By November 6, Guesclin was gathering an army in Caen. He brought together about 4,000 soldiers.

A second French force of about 1,200 men gathered further south. This group was led by Louis de Sancerre. Sancerre's force moved towards the English from the east. Guesclin moved towards them from the north. On December 1, Guesclin left Caen with his army. He marched south very quickly. Guesclin and his soldiers covered about 100 miles in just two days.

The Battles

Battle of Pontvallain

At Le Mans, Guesclin learned that Grandison's English force was nearby. They were trying to join up with Knolles. But Guesclin was faster. Even though his army was very tired, Guesclin ordered a night march. They reached Pontvallain by early morning on December 4. The French attacked Grandison's army without warning. This gave them a huge advantage.

The English were surprised. They probably only had time to form rough lines before fierce hand-to-hand fighting began. Earlier in the war, English longbow archers had been very effective against French cavalry. But in this battle, the French horses wore heavy armor (called barding). This made the English arrows much less effective. The English tried to escape through the woods. But they could not retreat to higher ground where they might have been able to defend themselves. Soon, Grandison's force was trapped and completely destroyed near the walls of the Château de la Faigne.

Many soldiers died on both sides. A French Marshal, Arnoul d'Audrehem, was badly wounded and died. Most of the English army was killed. Grandison and a few of his captains were among the few survivors. Guesclin captured them. After Grandison's defeat, the largest English force left was Fitzwalter's. Sancerre, who was still a few hours away, heard about the battle. He turned south to face Fitzwalter. Guesclin sent some of his army to chase Knolles. He then moved towards Fitzwalter with the rest of his soldiers. Fitzwalter managed to avoid being surprised in the open. He marched south, hoping to find safety inside the fortified Vaas Abbey.

Battle of Vaas

The abbey at Vaas had English soldiers from Knolles's army. Fitzwalter's men thought it would be a safe place. However, the French forces led by Sancerre reached the abbey at almost the same time as the English. The English soldiers inside the abbey could not set up a good defense. They had to try and fight off an immediate attack from Sancerre.

It seems that Fitzwalter's force managed to get inside the outer gate. But after tough fighting, Sancerre's troops forced their way into the abbey. The English defense quickly fell apart. When Guesclin arrived, the battle ended completely, becoming a total defeat for the English. Over 300 English soldiers were killed, not counting those captured. Fitzwalter himself was captured by a French commander.

What Happened Next

The few English soldiers who survived the battles were scattered and confused. John Minsterworth's group, which had not fought in either battle, immediately went to Brittany. Others went south. About 300 English survivors joined together. They took over Courcillon Castle and then marched towards the Loire River. Sancerre chased them closely. Many of Knolles's men left their castles and also headed to the Loire. This group included many wounded soldiers and looters. They joined the other English group, making it several hundred strong.

Guesclin kept chasing them closely. His constant ambushes and raids reduced the number of English soldiers. They finally reached a safe crossing point at Saint-Maur. Another English group, led by Calveley, had already crossed. A little beyond the crossing was a strong English garrison at a fortified abbey. Some of the English went east, but most continued towards Bordeaux. This group was still chased by Guesclin, now joined again by Sancerre. They were eventually trapped outside Bressuire Castle. This castle also had an English garrison. But the soldiers inside were afraid that if they opened the gates, the French army would get in too. So, they refused to open them. As a result, the rest of this English army was wiped out outside the castle walls.

Sancerre then took back the castles that Knolles had captured. Guesclin went back to Saint-Maur. He negotiated with the English soldiers inside the abbey and arranged for their release if they paid a ransom. The exact price is not known. Soon after, Guesclin returned to Le Mans.

It's not clear exactly where Knolles went in Brittany with his stolen treasure. He was soon joined by Minsterworth. They decided to return to England with most of their soldiers early the next year. They traveled to a port, but the French ambushed them many times along the way. When they arrived, there were only two small ships. These were not enough for the hundreds of men with Knolles and Minsterworth. More English soldiers, who had left their posts, also arrived at the port. Minsterworth was one of the few who could pay for a passage. Most of the others, about 500 men, were killed by the French who caught up with them.

When Minsterworth returned to England, it caused a lot of arguments. Even though he was just as responsible as Knolles, Minsterworth tried to blame Knolles for the military disaster. In July 1372, the King's council agreed with Minsterworth and blamed Knolles. The English nobles also blamed Knolles because he was not as high-ranking as them. But Minsterworth could not escape blame completely. The council later arrested him for falsely accusing Knolles.

Historians say that the Pontvallain campaign showed how amazing Guesclin was as a commander. He seemed to be everywhere at once. Many English knights were captured and sent to Paris as prisoners. Others spent huge amounts of money to avoid being captured. Fitzwalter was held prisoner until he could pay his ransom. He had to mortgage his lands to the King's mistress to do so.

What We Learned From It

Knolles's campaign cost King Edward a lot of money. One historian said it was "plunder but little military benefit." Another noted that even though Knolles reached Paris, he had little to show for it. This showed how much the Hundred Years' War had changed. The days when England won big battles like Crécy and Poitiers were over. Pontvallain, according to one expert, "destroyed the reputation the English had for invincibility on the battlefield."

England continued to lose land in Aquitaine until 1374. As they lost land, they also lost the loyalty of local lords. Pontvallain also ended King Edward's plan to form an alliance with the King of Navarre. It was also the last time England used large groups of mercenaries (soldiers who fight for money) in France. Most of their original leaders had been killed. Mercenaries were still used, but they became part of the main armies.

Hundreds of years later, when France lost some land to Germany, the Pontvallain campaign was used as an example of how France could make a great comeback. It helped keep alive the hope of getting their land back.

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |