Battle of Vågen facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Vågen |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Second Anglo-Dutch War | |||||||

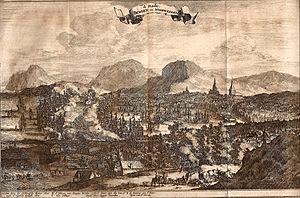

The attack on the Norwegian port of Bergen on Tuesday, August 12, 1665. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 8 warships | 14 warships | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 108 killed or wounded | 421 killed and wounded | ||||||

The Battle of Vågen was an exciting naval battle that happened in August 1665. It was fought between a group of Dutch merchant ships, loaded with valuable treasures, and an English fleet of warships. This battle was part of the Second Anglo-Dutch War, a big conflict between England and the Netherlands.

The fight took place in Vågen, which means "the bay" in Norwegian. This was the main port of Bergen, a city in Norway. At the time, Norway was a neutral country, meaning it wasn't supposed to take sides in the war. However, because of a mix-up with orders, the Norwegian commanders ended up helping the Dutch ships. This was actually against the secret wishes of the King of Norway and Denmark!

The battle ended with the English fleet having to retreat. Their ships were badly damaged, but none were sunk. The valuable Dutch treasure fleet was safe and later got help from the main Dutch fleet.

Contents

Arrival of the Treasure Fleet

The Dutch merchant fleet was huge, with about 60 ships in total. Ten of these were from the Dutch East India Company (VOC), led by Commodore Pieter de Bitter. These ships were returning from the East Indies, carrying the richest cargo ever seen at that time. Imagine ships filled with luxury goods like spices (pepper, cloves, nutmeg, cinnamon), silk, indigo dye, pearls, rubies, diamonds, and beautiful porcelain! This cargo was worth a huge amount of money, more than the Danish-Norwegian king's yearly income.

To avoid the English fleet, which was controlling the English Channel, the Dutch ships sailed north of Scotland. They hoped to reach the Dutch Republic by going through the North Sea. After a big storm scattered them, most of the ships found shelter in the neutral Bergen harbor in July. They waited there for the main Dutch fleet to be repaired after a recent defeat.

The English fleet, which was already in the North Sea, found out about the arrival of the Dutch treasure ships. This caused a big debate among the English commanders about what to do next. The fleet commander, Lord Sandwich, decided to split his fleet. He sent a smaller group of 14 warships, led by Rear-Admiral Thomas Teddeman, to Bergen. Their mission was to capture or block the valuable Dutch convoy.

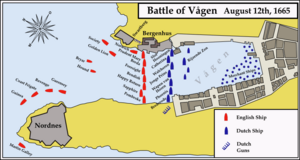

Teddeman's ships arrived at Bergen on August 1st and blocked the entrance to the bay. The entrance was quite narrow, only about 400 meters wide. This meant the English could only position seven of their ships to face the Dutch directly.

Secret Plans and Missed Orders

Bergen's harbor was protected by two fortresses, Bergenhus and Sverresborg. The commanders of these fortresses, Johan Caspar von Cicignon and Claus von Ahlefeldt, were approached by both the Dutch and English. The Norwegians decided to stay neutral at first. Ahlefeldt had heard rumors of a secret agreement between King Charles II of England and King Frederick III of Denmark-Norway. However, no clear orders had arrived for him. By treaty, only five warships from any nation were allowed in the harbor.

In reality, a secret deal had been made a week earlier. King Frederick III had agreed to let the English attack the Dutch ships, and the treasure would be split equally between England and Denmark-Norway. This was despite Denmark-Norway being officially allied with the Dutch! King Frederick sent an order to Ahlefeldt telling him to protest the English attack but not to stop it.

However, this important order did not reach Bergen in time. The English also sent a message to their fleet to wait for Ahlefeldt to get his orders, but the Dutch intercepted this messenger. So, Teddeman knew a deal was being made, but he didn't know the details or that he should wait. Both kings wanted the treasure for themselves, not for their countries' treasuries. This made the situation even more complicated.

Ready for Battle

When Teddeman sent his representative, Edward Montagu, to Bergen to plan the attack, the Danish-Norwegian commanders refused to help. Montagu returned to Teddeman, who then threatened the fortresses with force if they didn't cooperate. Montagu tried to impress them by saying the English fleet had 2000 cannons and 6000 men, but he was greatly exaggerating. He was also not taken seriously when he offered a special award, the Order of the Garter, in exchange for their help.

Meanwhile, the city of Bergen was in chaos. English sailors had come ashore to scare the people, and many citizens fled. The Dutch commander, De Bitter, quickly called his crews back to their ships by ringing the church bells. Many of his sailors were not experienced fighters, so he boosted their spirits by promising them three months of extra pay if they won. This promise was legally binding under Dutch law, and the news was met with great excitement!

De Bitter positioned his eight heaviest ships to face the English. These ships were deep inside the bay, about 300 meters from the English line. Thousands of sailors from the smaller Dutch ships were sent to help strengthen the fortresses on land.

The Battle Begins

Early in the morning of August 2nd, the English drums and trumpets sounded, letting the Dutch know that fighting was about to begin. The Dutch crews said a quick prayer and then quickly got ready at their cannons.

At six in the morning, cannon fire erupted! Both fleets were very close to each other, only hundreds of meters apart. Teddeman decided not to use "fireships" (ships loaded with flammable materials to set enemy ships on fire) because he didn't want to risk damaging the valuable Dutch cargo. Strong southern winds and rain blew the smoke from the English guns back onto their own ships, blinding them. This meant they couldn't see that the Dutch ships were barely being hit.

Because Bergen sticks out into the bay, the northernmost English ships had to shoot very carefully to hit the Dutch. One English cannonball accidentally landed in the Norwegian fortress, killing four soldiers. The Norwegian commander immediately fired back at the English fleet!

The English fleet had more cannons and men than the Norwegian fortresses. However, the English ships facing the Dutch were not in a good position to fire back at the Norwegians. Also, most English ships were frigates, which are smaller and can't take as much damage as the large Dutch merchant ships. The Dutch actually had more firepower in this close-quarters battle. Teddeman had hoped the Dutch would give up quickly, but they didn't.

After three hours of intense fighting, the English ships blocking the bay were defeated. Their panicked crews cut their anchor ropes to escape. Some ships got tangled and almost capsized. The English were forced to retreat at around 10 in the morning.

The English suffered heavy losses, with 421 casualties, including 112 dead (many of them captains) and 309 wounded. The Dutch ships were damaged, especially the Catherina, but they had far fewer casualties: about 25 dead and 70 wounded. A few Norwegians also died in the fortress and the city.

After the Battle

The orders from Copenhagen finally reached Ahlefeldt six days later, on August 8th. Since the Dutch ships were still in Bergen, Ahlefeldt went to the English fleet to try and fix things. He offered them another chance to attack without the fortress interfering. However, the English commander, Teddeman, refused. He knew he couldn't get his fleet ready in time. Also, Ahlefeldt refused to attack the Dutch himself.

In the days after the battle, the Dutch had made their position much stronger. They put a huge defensive chain across the entrance of the bay, and their sailors added 100 more cannons to the fortifications.

The English fleet eventually left Bergen. On August 19th, the main Dutch relief fleet, led by Michiel de Ruyter, arrived at Bergen. On August 29th, the Dutch merchant fleet finally left the harbor. The next day, a hurricane hit the convoy, scattering all 184 ships.

The English, led by Lord Sandwich, managed to capture a few straggling Dutch ships, including two valuable Dutch East India Company vessels. However, they missed the main Dutch fleet and most of the treasure ships. This was a huge disappointment for the English, who needed the treasure to pay for the war.

Lord Sandwich was blamed for the failure and lost favor with the King. He was later found to have secretly taken valuable goods from the captured Dutch ships. This caused more trouble for him.

The escape of the Dutch treasure fleet was a big blow to England. Samuel Pepys, a famous diarist, described the incredible wealth he saw on one of the captured ships: "Pepper scattered through every chink... in cloves and nutmegs, I walked above the knees; whole rooms full. And silk in bales, and boxes of copper-plate... which was as noble a sight as ever I saw in my life..."

In February 1666, Denmark-Norway officially declared war against England, after receiving a lot of money from the Dutch. Pieter de Bitter, the Dutch commander, received an honorary golden chain for his bravery.

One important result of the battle was the building of a new fortress, Fredriksberg Fortress, in Bergen. The battle had shown how vulnerable the city really was.

Legacy of the Battle

Today, you can still see a cannonball from the Battle of Vågen stuck in the wall of the Bergen Cathedral! In 2015, a special plaque was put up on the cathedral wall, and an information board was placed near the Bergenhus Fortress. The Bergen Maritime Museum also has parts of the decorations from the English ships on display, including wooden figures of a lion and a unicorn. In 2015, an exhibition called "Kings, spices and gunpowder" celebrated the 350th anniversary of the battle.

A famous painting of the battle was created by Willem van de Velde the Younger and can be seen at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, London.

Images for kids

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |