California Southern Railroad facts for kids

Route map of the California Southern Railroad upon its completion in 1885.

|

|

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | National City, California |

| Locale | San Diego – Barstow, California |

| Dates of operation | 1880–1889 |

| Successor | Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

The California Southern Railroad was a railway company that helped build train lines in Southern California. It was a part of the larger Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway (Santa Fe). The company started on July 10, 1880. Its main goal was to build a railroad connecting Barstow to San Diego, California.

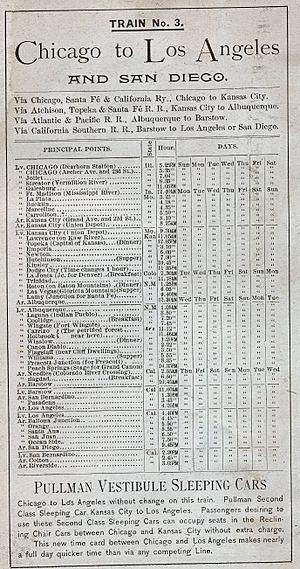

Building started in National City, near San Diego, in 1881. The tracks went north to Oceanside. From there, the line turned northeast through Temecula Canyon. It then continued to cities like Lake Elsinore, Perris, and Riverside. It connected with the Southern Pacific Railroad in Colton. There was a big argument, called a "frog war," because Southern Pacific didn't want the California Southern to cross its tracks. A court order allowed the California Southern to build its crossing. Construction then continued north through Cajon Pass to Victorville and Barstow. The line was finished on November 9, 1885. It became the western part of Santa Fe's main railway line to Chicago. Parts of this old line are still used today for busy freight and passenger trains in the United States.

Contents

Building the Railroad

The California Southern Railroad was created on July 10, 1880. Its purpose was to link San Diego with another railroad, the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad. Important people involved included Frank Kimball, a landowner from San Diego, and leaders from the Santa Fe railway. They aimed to finish the connection by January 1, 1884. This date was later changed because of problems building the Atlantic and Pacific line.

The California Southern started laying tracks north from National City, south of San Diego. The route connected many cities. These included National City, San Diego, Fallbrook, Temecula, Lake Elsinore, Perris, Riverside, San Bernardino, Colton, Cajon, Victorville, and Barstow. Many parts of this route are still used today.

In Barstow, the California Southern was supposed to connect with the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad. This other railroad was meant to build west from Springfield, Missouri, to the Pacific Ocean. However, the Southern Pacific Railroad built its own tracks from Mojave east to Needles, California. This line crossed the Colorado River on August 3, 1883. The Santa Fe later took over this part of the line.

Starting in San Diego

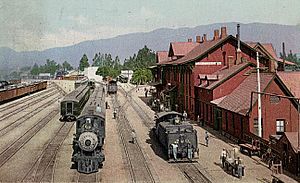

Construction for the California Southern began in National City. This land was bought by Frank Kimball. The railroad built its main train yards and repair shops here. All the tools and equipment for building the railroad came by ship to National City. These ships sailed all the way around Cape Horn from the eastern United States. Wooden ties for the tracks came by ship from Oregon. By March 1881, work between National City and San Diego was going well. The railroad reached Fallbrook and opened for service to San Diego in January 1882.

In 1881 and 1882, ten train engines arrived by sea at National City. The last three of these engines arrived in November 1882. They were the last train engines ever delivered to the U.S. Pacific coast by sailing around Cape Horn.

Trouble in Temecula Canyon

To connect quickly to the Atlantic and Pacific line, engineers decided to build through Fallbrook and Temecula. This route avoided Los Angeles. However, the railroad did not understand the dry riverbeds, called "dry washes," in Southern California. Local people warned the railroad that these areas could become fast-flowing rivers. But the railroad built the tracks through the canyon anyway.

Despite the warnings, track laying in the canyon was fast. The line reached Fallbrook on January 2, 1882, and Temecula on March 27, 1882.

In February 1884, heavy storms hit the canyon. The canyon walls crumbled, sending large rocks onto the tracks. On February 3, a train could not get through. A few days later, the communication wires were down. A train from Colton to San Diego was in danger. Luckily, a local person named Charlie Howell ran up the tracks and stopped the train. Then, starting on February 16, 1884, huge floods, called washouts, destroyed parts of the track in Temecula Canyon. This happened just six months after trains started running the full route between San Diego and San Bernardino. The storms brought over 40 inches (1,000 mm) of rain in four weeks. Two-thirds of the main track in the canyon were washed away. Train ties were found floating 80 miles (130 km) away in the ocean.

Temporary repairs were made after the first storms. But more rain and flooding later that month washed out the entire route through the canyon. Repairs would have cost about $320,000, which was too much money to make back.

The railroad stopped using the canyon route completely when the Surf Line was finished on August 12, 1888. The canyon line became a smaller, less important track. By 1900, the Santa Fe railway no longer used it. Later, in 1928, the Railroad Canyon Dam was built. This dam flooded the track section between Elsinore and Perris, creating Canyon Lake.

The Colton Crossing Fight

Building the California Southern was often stopped by its rival, the Southern Pacific Railroad (SP). One big problem happened when the California Southern wanted to build its tracks across the SP tracks in Colton. This crossing would break Southern Pacific's control over railroads in Southern California.

The Colton Crossing was the site of a famous "frog war" in American railroad history. In the summer of 1882, things got very tense. The Southern Pacific tried to stop the California Southern from finishing its tracks. The SP parked a train engine and a gondola car on its tracks where the crossing was planned. They also hired armed men, including the famous Virgil Earp, to guard the tracks. To prevent violence, Governor Robert Waterman ordered the local sheriff to make sure the court order was followed. The governor personally told Earp and the crowd to obey the court. Earp gave in and told the SP engineer to move the train. The crossing was built, ending Southern Pacific's control in Southern California.

Conquering Cajon Pass

The first train station the California Southern used in San Bernardino was a converted boxcar. Building north from San Bernardino, the California Southern used survey work already done by another railroad near Cajon.

The original slope of the tracks up the pass was 2.2% between San Bernardino and Cajon. Then, the slope got steeper, rising 3% for another 6 miles (10 km) to the top. The route over Cajon Pass was finished with a "last spike" on November 9, 1885. The first train to use the pass carried rails south from Barstow on November 12. These rails were used near Riverside. The first train to travel all the way from Chicago using Santa Fe lines arrived in San Diego on November 17, 1885.

Jacob Nash Victor, who was the General Manager of the California Southern, oversaw the building of the original route through Cajon Pass. He drove the first train through the pass in 1885. He famously said, "No other railroad will ever have the nerve to build through these mountains." For a while, he was right. Another railroad, the San Pedro, Los Angeles and Salt Lake Railroad, used the California Southern's tracks through the pass. However, Victor was proven wrong 80 years later. In 1967, the Southern Pacific built its own tracks, called the Palmdale Cutoff, at a slightly higher elevation through the pass. The city of Victorville was named after Jacob Nash Victor to honor his work.

Joining Other Railroads

To reach Los Angeles, the Santa Fe rented tracks from the Southern Pacific from San Bernardino starting November 29, 1885. This cost $1,200 per mile each year. The Santa Fe wanted to lower these costs. So, on November 20, 1886, the Santa Fe created a new company called the San Bernardino and Los Angeles Railway. This company would build a direct rail link between San Bernardino and Los Angeles. California Southern workers built this new line. The first train on the new line arrived in Los Angeles on May 31, 1887.

During this time, Santa Fe leaders worked to combine many smaller railroad companies in Southern California. This helped them save money. On May 20, 1887, the California Central Railway was formed by joining several of these companies. After this, the California Southern still existed but its main repair shops in National City were made smaller. The work moved to new shops in San Bernardino. In 1887, the California Southern was split into two parts for operations: the San Diego division (National City to Colton) and the San Bernardino Division (Colton to Barstow).

In 1889, the Santa Fe railroad went through big financial changes. New investors from New York and London took over. These new investors did not like having so many smaller companies. They wanted to combine them even more. So, on November 7, 1889, the California Southern, California Central, and Redondo Beach Railway companies were combined into the Southern California Railway. The Santa Fe finally bought the Southern California Railway completely on January 17, 1906. This made it a full part of the Santa Fe railroad.

Who Led the Company

The people who were president of the California Southern Railroad were:

- Benjamin Kimball (1880)

- Thomas Nickerson (1880-1885)

- George B. Wilbur (1885-1887)

- George O. Manchester (1887-unknown)

What You Can Still See Today

Much of the land where the California Southern built its tracks is still used today. Some buildings and structures built for the railroad, or their remains, can still be seen. Some of these old buildings are still used for their original purpose.

The two ends of the old railroad line are still very busy. The section between Barstow and Riverside, through Cajon Pass, is one of the busiest freight train routes in the United States. Trains from BNSF Railway and Union Pacific Railroad use it. Amtrak's daily Southwest Chief passenger train also uses this route. At Cajon, you can still see the concrete foundations where the old station and water tanks once stood. The Santa Fe changed the tracks in Cajon Pass over time. They straightened curves and lowered the slopes to make it easier for trains.

The train repair shops in San Bernardino are still used by BNSF Railway, but not as much as they used to be. The original San Bernardino station built by the California Southern burned down on November 16, 1916. A new station was built in 1918. This new station now serves Metrolink commuter trains. South of Riverside, the tracks are still in place to Perris. This section has been fixed up and is now part of the Perris Valley Line. This line extends Metrolink service to new stations. The Southern California Railway Museum, near Perris, used to connect to the main line. They hope to connect again and run trains to downtown Perris.

At the southern end, the section between San Diego and Oceanside is also very busy. Amtrak California's Pacific Surfliner trains and San Diego Coaster trains use it. This line is part of what is known as the Surf Line. As of 2006, it was the second busiest passenger train line in the United States.

San Diego's Union Station replaced the original station in 1915. However, the California Southern's original station and office building in National City has been saved. It is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |