Cartilaginous fishes facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Cartilaginous fishTemporal range: Lower Silurian – Recent

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Great white shark, Carcharodon carcharias | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Subphylum: | |

| Infraphylum: | |

| Class: |

Chondrichthyes

Huxley, 1880

|

Cartilaginous fish are a special group of fish that have skeletons made of cartilage instead of bone. Cartilage is a strong, flexible material, like what you have in your nose and ears. These fish also have jaws, paired fins, and scales. They are split into two main groups: Elasmobranchii (which includes sharks, rays, and skates) and Holocephali (like chimaeras, sometimes called ghost sharks).

Contents

What are Cartilaginous Fish?

Cartilaginous fish belong to a group called Chondrichthyes. This group is divided into two main types:

| Main Groups of Cartilaginous Fish | ||

|---|---|---|

| Elasmobranchii |

|

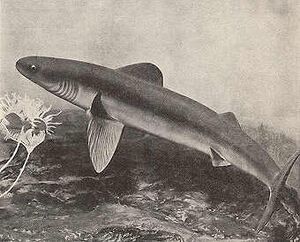

This group includes all the sharks, rays, and skates. They don't have a swim bladder, which is a gas-filled sac that helps bony fish float. Instead, they rely on their oily livers and fin shape to control their depth. They have five to seven pairs of gills that open separately to the outside. Their dorsal fins are stiff, and their skin is covered in tiny, tooth-like scales. Their teeth grow in many rows, and their upper jaw is not attached to their skull. You can find these fish in warm and cool waters all over the world. |

| Holocephali |

|

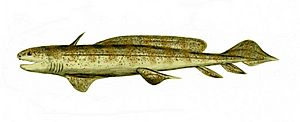

Holocephali means "complete-heads." This group includes fish like rat fishes, rabbit-fishes, and elephant-fishes, which are all types of chimaeras. They usually live near the bottom of the ocean and eat molluscs and other small creatures without backbones. They have long, thin tails and use their large pectoral fins to swim. Some even have a spine in front of their dorsal fin that can be poisonous! Unlike other fish, they don't have a true stomach; their gut is simpler. Their mouth is small and surrounded by lips, making their head look a bit like a parrot's. |

How Did They Evolve?

Cartilaginous fish have been around for a very long time! Their story goes back hundreds of millions of years.

Ancient Sharks

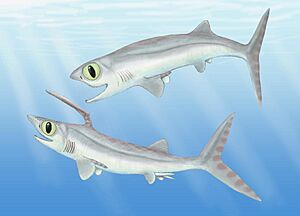

One of the earliest known sharks was Cladoselache, which lived about 370 million years ago during the Devonian period. It was about 6 feet (1.8 meters) long and looked a bit like modern mackerel sharks. It was very fast and agile, which helped it escape predators like the huge, armored fish Dunkleosteus. Cladoselache had a short, rounded snout and a mouth at the very front of its head. Its teeth were good for grabbing prey, but not for chewing, so it probably swallowed its food whole.

Sharks in the Carboniferous Period

During the Carboniferous period (about 359 to 299 million years ago), sharks became much more diverse. This happened because many other ancient fish groups died out, leaving new spaces for sharks to evolve and fill.

Some Carboniferous sharks, like Psammodus, had flat, crushing teeth to grind up shells. Others, like the Symmoriida, had sharp, piercing teeth. Most sharks lived in the ocean, but some, like the Xenacanthida, moved into freshwater swamps.

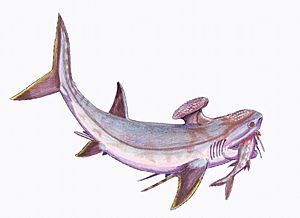

Some ancient sharks had very unusual shapes. For example, Stethacanthus had a flat, brush-like fin on its back with tiny, tooth-like scales on top. Scientists think this strange fin might have been used in mating rituals.

Another interesting shark was Falcatus, which was only about 10-12 inches (25-30 cm) long. It had a unique fin spine that curved forward over its head.

Orodus was another type of shark from this time, growing up to 6.5 feet (2 meters) long.

Later Periods and Extinctions

The Permian period ended with a huge extinction event about 252 million years ago, where most marine and land species died out. It took a very long time for life to recover.

The Triassic period (252 to 201 million years ago) saw a more uniform fish population because only a few families survived the Permian extinction. The Triassic also ended with another extinction event.

Even though many species died out in these events, cartilaginous fish like sharks and rays were quite resilient. For example, about 80% of shark, ray, and skate families survived the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event (K-Pg extinction) that wiped out the dinosaurs about 66 million years ago.

During the Cretaceous period (145 to 66 million years ago), sharks like Squalicorax falcatus lived.

Ptychodus was another shark from the late Cretaceous, known for its large, crushing teeth. Ptychodus mortoni was about 32 feet (9.8 meters) long!

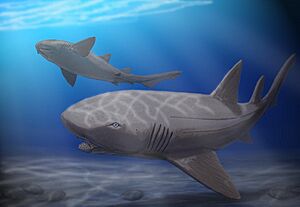

The Cenozoic Era and Megalodon

The Cenozoic Era (65 million years ago to today) has seen many new types of bony fish, but also some incredible cartilaginous fish. One of the most famous is the Megalodon. This extinct shark lived about 28 to 1.5 million years ago. It looked like a giant, super-strong version of a great white shark, reaching lengths of over 66 feet (20 meters)! Megalodon was one of the biggest and most powerful predators in Earth's history, and it had a huge impact on ocean life.

Images for kids

-

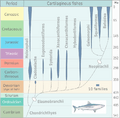

Radiation of cartilaginous fish, based on Michael Benton, 2005.

See also

In Spanish: Peces cartilaginosos para niños

In Spanish: Peces cartilaginosos para niños

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |