Charles Atherton (civil engineer) facts for kids

Charles Atherton (born 1805 – died 1875) was a clever British engineer from Calne, Wiltshire. He became a very important person in the British Navy's dockyards. He was the Chief Engineer and Inspector of Steam Machinery at Woolwich Dockyard from 1847 to 1848, and again from 1851 to 1862. He also worked at Devonport Dockyard from 1848 to 1851.

Contents

Early Life and Learning

Charles Atherton grew up in a wealthy family in Wiltshire. His father, Nathan Atherton, was a lawyer.

When he was 19, Charles went to Queens' College, Cambridge. He studied there for four years, learning everything he needed to become an engineer.

A Career in Engineering

Charles Atherton became a scientific engineer at a time when engineering was still quite new. There weren't many fixed rules yet. He focused on marine engineering, which meant working with steamships. Back then, steamships were just starting to become popular.

After finishing college, he worked for a famous engineer named Thomas Telford. He helped build the St Katharine Docks in London. When that project finished in 1830, he moved to Edinburgh. There, he helped build the Dean Bridge. He even wrote about how it was built for the Encyclopedia Britannica.

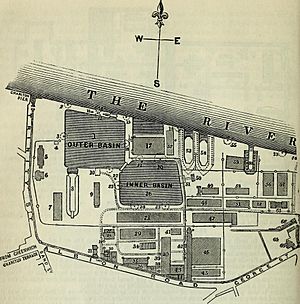

In 1832, Atherton moved to Glasgow. He first helped build the Glasgow Bridge. Then, he became the main engineer for the River Clyde Trustees, helping to manage the river.

He designed a plan to make a wooden dock bigger at Broomielaw Harbour. In 1834, he left that job to manage a company called Claude Girdwood and Co in Glasgow. This company made iron and engineered things. Here, Atherton really focused on designing and building steam engines. He made several engines for ships, including one for a steamer called RMS Don Juan. This ship was being built in Liverpool for the Peninsular Steam Company.

Atherton also worked on a big project in Mechelen, Belgium, on the Dyle River. After that, he moved to North America. For two years, he worked for the Canadian government. He helped make the St. Lawrence River easier for ships to use. He also helped make the Lachine Canal deeper so bigger ships could pass through. He even surveyed Lake Saint Pierre. After Canada, he spent a year working in the United States before returning to England in 1845.

Working at Woolwich Dockyard

In 1846, Charles Atherton became an assistant engineer at Woolwich Dockyard. On April 6, 1847, he became the Chief Engineer. In the years before he arrived, the dockyard had become a special place for marine steam engineering. This was a new technology that was being developed nearby.

New buildings were built for making and fixing steam engines. These included a boiler shop, foundries for different metals, and a shop for putting steam engines together. By 1843, all these buildings were part of one big factory. It even had a huge chimney that connected to all the furnaces. Two old mast ponds were turned into steam basins. Ships could dock there while their engines and boilers were installed. One of these basins had its own dry dock. Even though the steam factory was part of the dockyard, it was quite independent. It had its own gate and its own boss, the Chief Engineer.

As Chief Engineer, Atherton often had to speak to Parliamentary Committees about the dockyard. His ideas in 1847 were approved, which helped the dockyard build more ships and use new technology.

The Illustrated London News reported in 1847 that Atherton showed the Russian Royal family around Woolwich Dockyard. He showed Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolayevich of Russia how advanced British steam technology was.

In 1848, Atherton improved a steam ship called Minx. He suggested a small change to a new type of screw propeller. This change helped the ship go faster, at nine knots per hour.

Atherton was very important to the British government. He sent his engineering ideas to the Admiralty (the government department in charge of the Navy). His reports were not just about engine details. They also covered engineering methods and how to make steam ships safer. Some of his ideas included:

- Engine Classification (1846)

- Proposal for making the Government Factories Practical Training schools for Naval Engineers (1847)

- Marine Boiler Classification (1847 and 1848)

- Steam-ship Ventilation by the Agency of the Funnel

- Proposed Boiler Arrangement for Ships of War (1849 and 1850)

He even got a patent for his "Steam Engine" in 1850.

Atherton lived during a time of fast industrial growth. He showed his inventions at the famous Great Exhibition of 1851.

His scientific, engineering, and educational writings were published by John Weale. He wrote about:

- Marine Engine Construction and Classification (1851)

- Steam-ship Capability (1853)

- Capability of Steamships for Mercantile Transport Service (1855), which won him a medal from the Royal Society of Arts.

He also wrote about how to register the size of ships, how to make steam transport cheaper, and how different ship designs affected freight costs.

In December 1848, he moved to Devonport Dockyard as Chief Engineer. He stayed there until September 1851, when he returned to Woolwich Dockyard. He worked there until he retired from government service in 1862.

After retiring from the government, Atherton became a consulting engineer in Whitehall. His wide experience in building and mechanical engineering made him perfect for this job. He worked as a consultant for eight more years. During this time, he continued to get patents for things like buoys, pontoons, and beacons in different countries. His last patent was about steering ships.

A Lasting Impact

Charles Atherton made a big difference in making all kinds of ships safer – cargo ships, passenger ships, and Royal Navy ships. His work likely saved many lives by reducing accidents caused by carelessness or mistakes.

During his lifetime, government officials had to check passenger steamers regularly. They had to make sure the "Hull & Machinery" of the ship was safe before it could carry passengers. If a ship wasn't safe, it couldn't take passengers. His detailed reports and ideas were even used by important people like Thomas Farrer, 1st Baron Farrer when he talked with Michael Faraday in 1859.

He wrote many articles for newspapers like The Times, Mechanics Magazine, and the Journal of the Society of Arts. He also helped test people who wanted to become engineers in special fields.

The National Portrait Gallery, London has a silhouette (a dark outline picture) of Atherton from 1830, made by Auguste Edouart.

Memberships

Charles Atherton was a member of the Institution of Civil Engineers, which started in 1818. He joined on February 19, 1828, when Thomas Telford was the president. He often went to their meetings and used them to share his ideas about improving marine steam engines.

Personal Life

Charles Atherton married Christina Ferrie (1813–1862). She was the daughter of Robert Ferrie from Glasgow.

His brother, Nathan Atherton, was also a lawyer in London. Nathan's wife, Sabina Atherton, visited Charles at his home in Devonport in 1851.

In 1870, Atherton retired to Sandown on the Isle of Wight. He spent his last five years there quietly. He enjoyed taking care of his orchard-house and looking at the stars with his telescope. He passed away at his home on the Isle of Wight on May 24, 1875, at the age of 75.

See also

- Henry Bell (engineer), another early steamship engineer