Charlotte Stuart, Duchess of Albany facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Charlotte Stuart

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait by Hugh Douglas Hamilton, Scottish National Portrait Gallery

|

|

| Born | 29 October 1753 |

| Died | 17 November 1789 (aged 36) Palazzo Vizzani Sanguinetti, Bologna

|

| Title | Duchess of Albany |

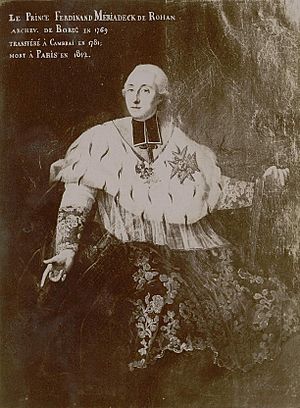

| Partner(s) | Ferdinand Maximilien Mériadec de Rohan |

| Children |

|

| Parent(s) | |

Charlotte Stuart, also known as the Duchess of Albany (born October 29, 1753 – died November 17, 1789), was the only child of Charles Edward Stuart, often called "Bonnie Prince Charlie." He was a Jacobite leader who claimed the British throne. Charlotte was his only child to survive past infancy.

Her mother was Clementina Walkinshaw, who was Prince Charles's partner from 1752 to 1760. After a difficult time, Clementina left him, taking Charlotte with her. Charlotte spent most of her life in convents in France, separated from her father. He refused to provide for her.

Since she couldn't marry officially, Charlotte had three children with Ferdinand Maximilien Mériadec de Rohan, who was an Archbishop.

In 1784, Charlotte finally reunited with her father. He officially recognized her as his daughter and gave her the title Duchess of Albany. She left her children with her mother and became her father's caregiver. She stayed with him during his last years. Charlotte died less than two years after her father. Her three children grew up without their royal connection being widely known. However, as Prince Charles Stuart's only grandchildren, they became important to people interested in the Jacobite cause after their family line was discovered in the 20th century.

Contents

Charlotte's Royal Family Connections

Charlotte Stuart was born on October 29, 1753, in Liège. Her parents were Prince Charles and his partner, Clementina Walkinshaw. Charles and Clementina first met during the Jacobite rising of 1745. This was when Charles came to Scotland from France. He was trying to take back the thrones of England, Scotland, and Ireland. His grandfather, James II and VII, had lost these thrones in 1689.

Clementina was the youngest of ten daughters. Her father, John Walkinshaw, was a rich merchant from Glasgow. He was also a Jacobite who had fought for Prince Charles's father in an earlier uprising in 1715. He was captured but escaped and went to Europe. Later, he was forgiven by the British government and returned to Glasgow. Clementina was mostly educated in Europe and became a Roman Catholic. In 1746, she was living with her uncle near Stirling. Prince Charles visited her uncle's home and met Clementina there. She helped nurse him when he was sick.

After Charles's rebellion was defeated in 1746, he fled Scotland for France. In 1752, he heard Clementina was in Dunkirk and needed money. He sent her gold coins and asked her to join him in Ghent. The couple then moved to Liège. Charlotte, their only child, was born there on October 29, 1753. She was baptized in the Catholic church in Liège.

Life Apart from Her Father (1760–1783)

The relationship between Prince Charles and Charlotte's mother was very difficult. By 1760, they were in Basel, and Clementina was tired of Charles's lifestyle. She contacted Charles's father, James Stuart, who was a strong Catholic. Clementina wanted Charlotte to have a Catholic education and wished to live in a convent. James agreed to give Clementina a yearly payment of 10,000 French livres. In July 1760, he may have helped her escape from Charles. Clementina took seven-year-old Charlotte to a convent in Paris. She left a letter for Charles, saying she had to flee for her safety. Charles was furious and tried to find them, but he failed.

Appeals from France

For the next twelve years, Clementina and Charlotte lived in different French convents. They were supported by the yearly payment from James Stuart. Charles never forgave Clementina for taking his child. He stubbornly refused to pay anything for them. On January 1, 1766, James died. Charles now considered himself King Charles III. Still, he refused to help Clementina and Charlotte. Clementina, calling herself Countess Alberstroff, had to ask Charles's brother, Henry Benedict Stuart, for help. Henry gave them 5,000 livres a year. In return, he made Clementina state that she had never been married to Charles. She later tried to take back this statement.

In 1772, Prince Charles married Princess Louise of Stolberg-Gedern. Charlotte, who was very poor, had been writing to her father for some time. She now desperately asked him to officially recognize her as his daughter. She also asked him to provide support and bring her to Rome before he had another child. In April 1772, Charlotte wrote a heartfelt letter to her "August Papa." Charles finally agreed to bring Charlotte to Rome. He was living in the Palazzo Muti, the home of the Stuart family in exile. But he had one condition: she had to leave her mother behind in France. Charlotte loyally refused to do this. Charles became angry and stopped all discussions.

Charlotte's Own Family

Towards the end of 1772, Clementina and Charlotte unexpectedly arrived in Rome. They wanted to plead their case in person. However, Prince Charles reacted angrily. He refused to even see them. This forced them to return to France, where Charlotte continued to send pleading letters. Three years later, Charlotte, now 22, was not well. She seemed to have a liver problem, which was common in the Stuart family. She decided her only choice was to marry as soon as possible. Charles, however, refused to let her marry or become a nun. She was left waiting for his decision.

Because she wasn't officially recognized or allowed to marry, Charlotte couldn't have a proper wedding. So, she found someone to protect and provide for her. Without Charles knowing, she became the partner of Ferdinand Maximilien Mériadec de Rohan. He was the Archbishop of Bordeaux and Cambrai. Ferdinand de Rohan was related to the Stuart family. He also couldn't marry officially because he had joined the Church as a younger son of a noble family. With him, Charlotte had three children: two daughters, Marie Victoire and Charlotte, and a son, Charles Edward. Her children were kept secret and were mostly unknown until the 20th century. When Charlotte finally left France for Florence, she left her children with her mother. She had just recovered from giving birth to her son. It seems few people, especially not her father, knew her children existed.

Reunion with Her Father

Only after his marriage to Louise ended, and Charles became very ill, did he show interest in Charlotte. She was now 30 years old and had not seen her father since she was seven. On March 23, 1783, he changed his will to make her his heir. A week later, he signed a document officially recognizing her as his daughter. This document, which also allowed her to inherit his private property, was sent to Louis XVI of France. Henry Stuart, Charles's brother, argued that the recognition was not done properly. King Louis XVI eventually confirmed the document and registered it in Paris, but not until September 6, 1787.

In July 1784, after officially separating from his wife Louise, Charles wrote to his daughter. He called her "my dear daughter" and asked her to come to Florence, where he was living. She arrived in Florence on October 5, 1784. In November, he set her up in a palace as the Duchess of Albany, calling her "Her Royal Highness". However, because she was born outside of marriage, Charlotte still had no right to claim the British throne. By this time, the claims were not very important. European rulers had stopped taking Charles seriously. Even Pope Pius VI refused to recognize his royal title. He was simply calling himself the Count d'Albany.

Even though a Stuart return to the throne was very unlikely, Prince Charles presented Charlotte as the next generation of their cause. On November 30, 1784, Charles held a special dinner for Charlotte. He gave her the Order of the Thistle. He also had medals made for her. These medals showed the figure of Hope, a map of England, and the Stuart family symbol. They had sayings like "Spes Tamen Est Una" ("there is one hope"). He also had artists paint her. The Scottish artist Gavin Hamilton drew her, and Hugh Douglas Hamilton painted a flattering portrait of her wearing a tiara.

Being Her Father's Companion

When Charlotte came to live with her father in 1784, he was suffering from mental decline. He used a special chair to travel. However, he did introduce Charlotte to society. He allowed her to wear his mother's famous Sobieska jewelry. She often tried, without success, to get jewels or money from her father, who was careful with his money. She probably wanted these things to help her mother and children. Within a month of arriving in Florence, she did manage to convince her father to finally provide for Clementina. By this time, Charlotte was also not in good health.

Charlotte greatly missed her mother (whom she hoped Charles would let come to Rome) and her children. She wrote to her mother as many as 100 times in one year. She was successful in helping to organize her father's social life. When staying in Pisa with her father, she made a separate visit to her uncle Henry Stuart in Perugia. There, she successfully arranged for Henry and Charles to reconcile.

Charlotte's Final Months

In December 1785, Charlotte asked Henry Stuart for help to get Charles back to the Palazzo Muti in Rome. When they arrived in Rome, the Pope welcomed Charlotte as the "Duchess of Albany." In Rome, Charlotte continued to care for her father and be his companion. She did her best to make his life comfortable until he died of a stroke two years later, on January 30, 1788. Her sacrifice for him was great. She was torn between her clear affection for her father in Rome and her mother and three children left behind in Paris. When her father died, the French court gave her a yearly payment of 20,000 livres. Charlotte inherited much of her father's property, including his home in Florence, furniture, and decorations. However, many of the Sobieski family jewels went to Henry Stuart. She later sold the Florentine palace and many of the possessions.

Charlotte spent much of her final months with Henry Stuart. She also became the godmother to Countess Mary Norton, a member of her court. Charlotte wrote to her mother about her worsening health. She made several trips to spa towns to improve her health. These included Nocera in Umbria and Bologna, where she sought medical treatment. Charlotte lived only twenty-two months longer than her father. She never saw her children again. On October 9, 1789, while staying in Bologna at the Palazzo Vizzani Lambertini Sanguinetti, she died at age 36 from liver cancer. In her will, written just three days before her death, Charlotte left her mother 50,000 livres and a yearly payment of 15,000. Her personal belongings, jewels, and other property went to Henry. However, it took two years for Henry Stuart, who was in charge of her will, to release the money. He only agreed to do this when Clementina signed a document giving up any further claim on the estate for herself and her descendants. Charlotte was buried in the Church of San Biagio, as she had asked in her will.

Charlotte's Legacy

For many years, Charlotte's three children were unknown to history. People believed that the direct family line of James II ended with Henry's death in 1807. However, in the 1950s, historians Alasdair and Hetty Tayler discovered that Charlotte had two daughters and a son. The historian George Sherburn then found letters from Charlotte to her mother. He used these letters to write a book about Charles Edward.

Charlotte's Children

It seems that Clementina lived in Fribourg, Switzerland, until she died in 1802. She raised Charlotte's children in secret. Their identities were hidden using different names and tricks. They were not even mentioned in Charlotte's detailed will. The will only referred to Clementina and Charlotte's wish that Clementina could help "her necessitous relations." The children's identities were kept secret because the relationship between Archbishop Ferdinand de Rohan and Charlotte was not allowed and would have caused a scandal.

Marie Victoire Adelaide (born 1779) and Charlotte Maximilienne Amélie (born 1780) were thought to have been cared for by Thomas Coutts, a London banker. They remained unknown and were believed to have simply joined English society.

Charlotte's son Charles Edward (born in Paris in 1784) had a different life. Calling himself Count Roehenstart (a mix of Rohan and Stuart), he was educated by his father's family in Germany. He became an officer in the Russian army and a general in the Austrian army. He traveled widely, visiting India, America, and the West Indies. Later, he came to England and Scotland. He told such amazing stories about his background and adventures that few believed his claims of royal descent. It wasn't until the 20th century that historian George Sherburn proved he was who he claimed to be. He died in Scotland in 1854 after a coach accident near Stirling Castle. He was buried at Dunkeld Cathedral, where his grave can still be seen. He married twice but had no children.

It was generally believed that Charlotte's daughters also died without having children. However, Peter Pininski, in his 2002 book, suggested that Charlotte's daughter, Victoire Adelaide, did have children. Pininski claimed that in 1793, at the start of the French Revolution, Victoire Adelaide de Rohan went to relatives in Poland. There, she met and married Paul Anthony Louis Bertrand de Nikorowicz, a Polish nobleman. They had a son, Antime, and a daughter, Julia-Thérèse. Julia-Thérèse married Count Leonard Pininski and became Peter Pininski's great-great-grandmother. Pininski's evidence has been described as "often indirect."

However, Pininski's idea has been challenged by genealogist Marie-Louise Backhurst in articles published in 2013, 2021, and 2023. Backhurst provides evidence that Charlotte's second daughter, Victoire Adelaide, first married a military doctor in Paris in 1804. The marriage record shows her as Victoire Adelaide Roehenstart, daughter of Maximilien and his wife, Clementine Ruthven, the same parents as her brother Charles. With this doctor, she had a son, Theodore Marie de St Ursin, born in Paris in 1809. He died as a deacon in 1838. In 1823, his mother married again to a naval officer. Backhurst concludes that Madame Nikorowicz was actually Marie Victoire de Thorigny. She was more likely the daughter of Jules, Prince de Rohan, who was Ferdinand's brother. This would make her a first cousin to Victoire Adelaide, without the Stuart family connection.

In Jacobite Stories

Charlotte Stuart's story quickly became part of Jacobite folklore. The Scottish poet, Robert Burns (1759–1796), who lived around the same time, wrote many works celebrating the sad and romantic side of the Jacobite cause. One of these was The Bonnie Lass of Albanie. This poem was a lament, or sad song, about Charlotte Stuart. It was probably written around the time of her death.

|

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |