Cheyenne and Arapaho Indian Reservation facts for kids

The Cheyenne and Arapaho Indian Reservation was land set aside for the Southern Cheyenne and Southern Arapaho people. The United States government created it through the Medicine Lodge Treaty in 1867. However, the tribes did not want to live on the land first described in the treaty.

So, on August 10, 1869, President Ulysses S. Grant issued an executive order. This order set aside different lands for the tribes. These new lands were closer to their traditional homes. Today, this area is known as the Cheyenne-Arapaho Oklahoma Tribal Statistical Area.

Contents

Life on the Reservation: Challenges and Changes

The Last of the Buffalo Herds

After the Red River War, most Southern Cheyenne and Southern Arapaho people moved to the reservation. The government had promised food and supplies, but these were often not enough. The tribes also faced many illnesses.

The Indian Agent, John DeBras Miles, tried his best to help. But the government did not send enough money. Also, some Texas cattlemen illegally grazed their cattle on the reservation. This meant less food for the tribes.

The army worried about conflict, so they held back ammunition from the tribes. This left the tribes unprotected from white horse thieves. Some Cheyenne women earned money by tanning animal hides for traders. From 1875 to 1877, the tribes had to compete with white hunters for the last buffalo. By 1877, very few buffalo were left.

Northern Cheyenne Move South

In 1877, nearly a thousand Northern Cheyenne people came to the reservation. They were either escorted or came on their own. Like the Southern tribes, they did not get enough food or medical care.

In September 1878, a group led by Dull Knife and Little Wolf escaped. They fled north in what is called the Northern Cheyenne Exodus. Some were caught and brought back. But most Northern Cheyenne stayed on the reservation in Indian Territory. By 1883, those who wanted to return north were allowed. The Tongue River Indian Reservation was created for them in 1884.

Farming, Learning, and Work

In the late 1870s and early 1880s, both the Cheyenne and Arapaho tried farming. The Arapaho were more successful at it. But frequent droughts caused crops to fail. It took years for them to learn dryland farming methods. This included ways to save winter moisture.

Some men earned money by hauling supplies, making hay, and cutting wood. More children started attending Indian boarding schools. These included schools on the reservation and the Carlisle Institute in Pennsylvania.

However, it was hard for the Cheyenne and Arapaho to find work. Even graduates from Carlisle struggled to find jobs when they returned. An attempt to build a cattle herd for the tribes ended when the government ordered it to be given away. Each family received only about three cattle, which was not enough to be helpful. Food shortages continued, and the Indian agent had few ways to create work for the people.

Grazing Licenses and Conflicts

From 1882 to 1885, most of the reservation land was licensed to large cattle companies. They paid very little for this use. The Indian agent, John DeBras Miles, held a meeting in 1882. He believed he got permission from most tribal leaders for these grazing permits.

However, there was strong opposition, especially among the Cheyenne at Cantonment. They killed some cattle for food and as a way to resist. Some Cheyenne groups started punishing those who farmed or sent their children to school.

Miles resigned in 1884. His replacement, D. B. Dyer, had a difficult relationship with the Cheyenne. Conflicts between the tribes and cattlemen grew worse. In July 1885, President Grover Cleveland ordered the cattlemen off the reservation. The area was then placed under military control.

The Dawes Allotment Act

The Medicine Lodge Treaty had set aside a large part of western Oklahoma for the Cheyenne and Arapaho. The treaty said that no one else could settle on this land.

But in 1890, the United States broke this treaty. They used the Dawes Act to divide the land. Each family received a 160-acre parcel for farming. The remaining land was called "surplus" and sold to settlers. The government believed this would help Native Americans fit into American society. They also wanted to end tribal governments and shared land ownership.

The Bureau of Indian Affairs held the land in trust. They leased much of it to settlers. By 1910, most of the reservation land was controlled by settlers. The Native Americans became a small minority on their own land. On April 19, 1892, the reservation lands were opened for homesteaders. The tribes kept about 529,962 acres (2,144.76 km2) mostly along the Canadian and Washita Rivers.

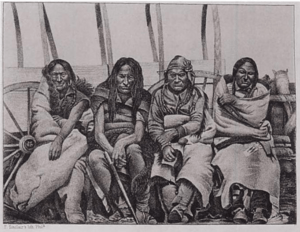

The Cheyenne People

In Oklahoma, the Cheyenne people live near towns like Thomas, Clinton, Weatherford, and El Reno. They are a Plains Tribe and speak an Algonquian language.

The Cheyenne have a long history with the Arapaho. In Oklahoma, they are called the Southern Cheyenne and Southern Arapaho. This helps tell them apart from their northern relatives in Montana and Wyoming. The southern groups were forced to move to Indian Territory after the 1867 Medicine Lodge Treaty. Chief Little Raven signed this treaty for the Southern Arapaho.

The Arapaho People

In Oklahoma, the Arapaho people mostly live in rural areas. These are near towns like Canton, Greenfield, Geary, and Colony. The name Arapaho comes from a Pawnee word meaning "He buys or trades." This might be because they were important traders in the Great Plains. The Arapaho call themselves Inun-ina, which means "our people."

The Arapaho are also part of the Algonquian language family. Northern Arapaho people in Wyoming call the Oklahoma group Nawathi'neha, meaning "Southerners."

In 1870, the Arapaho kept a tribal government. Twelve chiefs were chosen, including Jesse Rowlodge, David Meat, and John Hoof. Two Cheyenne men, Ben Buffalo and Ralph Whitetail, were also chosen to serve as Arapaho chiefs.

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |