Comet Line facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Belgian Resistance |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Resistance during World War II | |||||||

Andrée de Jongh, head of the Comet Line, receiving the George Medal in 1946 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

The Comet Line (French: Réseau Comète) was a brave secret group during World War II. It operated from 1941 to 1944 in Belgium and France, which were controlled by Nazi Germany. This group helped Allied soldiers and pilots who were shot down. Their goal was to help these brave people escape capture by the Germans. They would then guide them safely back to Great Britain.

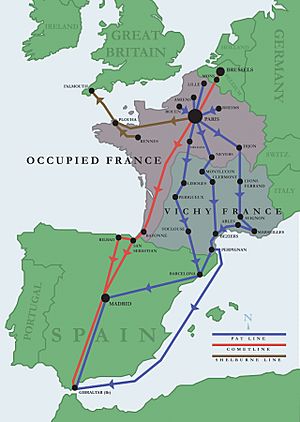

The Comet Line started in Brussels, Belgium. Here, downed airmen received food, clothes, and fake identity papers. They were hidden in safe places like attics and cellars. A large group of volunteers then helped them travel south. They went through German-controlled France into neutral Spain. From Spain, they reached Gibraltar, which was controlled by the British. Finally, they could return home. The Comet Line's motto was "Pugna Quin Percutias." This means "fight without arms," because they did not use weapons.

The Comet Line was the biggest escape network in Europe during the war. In three years, they helped 776 people escape. Most of these were British and American airmen. About 3,000 everyday people, mostly Belgians and French, helped the Comet Line. These helpers faced great danger. Seven hundred helpers were arrested by the Germans. Sadly, 290 of them died in prison or concentration camps. The Comet Line got money from MI9, a British spy agency. MI9 helped rescue Allied soldiers, but the Comet Line stayed independent.

Rescuing downed airmen was very important for the Allies. Training new pilots was expensive and took a lot of time. So, getting experienced airmen back to duty was a top priority. Andrée de Jongh, a 24-year-old Belgian woman, was the first leader of the Comet Line. She was captured in 1943 but survived the war. Other leaders were also captured or died. Many young women, including teenagers, played key roles. About 65 to 70 percent of Comet Line helpers were women.

Contents

How the Comet Line Started

In 1941, more and more British planes were shot down over German-controlled Europe. Most pilots were killed or captured. But some managed to hide. They were helped by people who supported the Allies. These helpers were part of a growing secret movement against German rule. In Belgium, Andrée de Jongh (Dédée), age 24, Arnold Deppé, age 32, and Baron Jacques Donny, age 47, started the Comet Line. They wanted to help Allied airmen escape back to the United Kingdom.

In June 1941, Arnold Deppé traveled to southwestern France. He looked for ways to sneak people out of Belgium. He met the de Greef family in Anglet, near the Spanish border. They agreed to help. Elvire De Greef became a very important helper. She was known as French: Tante Go (Auntie Go).

In July 1941, Dédée and Deppé tried their first escape. They had 10 Belgian men and a secret agent with them. After crossing into Spain, they left the group. But the Belgians were arrested by Spanish police. Three soldiers were even given back to the Germans. Dédée and Deppé learned a valuable lesson. They realized they had to go with their groups all the way. They needed to reach the British Consulate in Bilbao, Spain.

In August, Deppé and Dédée tried again. An informer betrayed Deppé. He and his group were arrested by the Germans. Deppé stayed in prison for the rest of the war. Dédée made it safely to the de Greef's house. She crossed into Spain with a guide. Dédée and her group reached the British Consulate in Bilbao. She convinced the British government to pay for the Comet Line's costs. This money helped transport Allied soldiers and airmen.

MI9, a British intelligence group, approved the money. Dédée insisted that the Comet Line stay independent. She didn't want the British or Belgian governments to control their operations. She felt they didn't understand the dangers. MI9 found this difficult at times. For a long time, the Comet Line refused radios from the British. They worried that radios could be captured and expose the network. Instead, they used couriers to send messages.

Helping Airmen Escape

After Arnold Deppé's arrest, the Comet Line became more careful. Andrée de Jongh moved to Paris for safety. Her father, Frederic (code name "Paul"), took over in Belgium. His job was to find downed airmen and hide them. He also gave them fake papers and new clothes. He taught them how to act like Europeans. Then, an escort would take them to Paris or all the way to Spain.

Andrée de Jongh was often the escort. She made 24 trips across the Pyrenees mountains. She helped 118 airmen escape. Other people also helped guide airmen across the border. The Comet Line often used Basques as guides. These were people used to secretly crossing the French-Spanish border. Florentino Goikoetxea was a favorite guide. He was wanted by both French and Spanish police. German police tried harder to stop these escape groups. This was because Allied bombing of Europe was increasing.

The Comet Line had three main centers: Brussels, Paris, and southwestern France. When the Germans got closer in Belgium, Frederic de Jongh ("Paul") moved to Paris. He managed the Paris center. Three Comet Line leaders in Belgium were arrested soon after. Jean Greindl ("Nemo"), age 36, took over in Belgium. He organized how to collect airmen and prepare them for escape. Young escorts like Andrée Dumon ("Nadine"), age 19, took airmen from Brussels to Paris.

In Paris, the de Jonghs took over. They provided safe houses and fake documents. An escort, usually Andrée de Jongh, took them by train to southwestern France. In cities like Bayonne, the airmen met Elvire de Greef or her teenage daughter, Janine. From there, the airmen, a Basque guide, and their escort walked over the Pyrenees mountains into Spain. In San Sebastián, Spain, a British car picked them up. They were driven to Madrid and then to Gibraltar. From Gibraltar, they flew back to Britain.

By spring 1944, the Allies were planning to invade France. The Comet Line decided to stop moving airmen. Instead, they gathered them in forest camps. There, the airmen waited for the Allied armies to arrive. This was part of a plan called Operation Marathon. The last people to escape were mostly Comet Line members. They were running from German arrests. The Comet Line's last operation was on September 28, 1944. Elvire De Greef, now in liberated France, flew four Allied airmen to England.

Young people, especially young women, often worked for the Comet Line. They dressed and acted like students. Their fake ID cards often made them seem younger than they were. The idea was that younger people might not be suspected by the Germans. For example, Andrée de Jongh's fake ID said she was almost eight years younger.

A Dangerous Journey

The story of one Canadian airman, Sergeant Sydney Smith, shows how many people helped. It also shows how complex these escapes were. The Comet Line helped 101 groups escape during the war. Each escape involved many helpers and guides.

On December 9, 1942, Sergeant Sydney Smith's plane was shot down in France. He hid, and a farmer named Emile Cochin helped him. The farmer contacted Madeleine de Brunel de Serbonnes, who spoke English. She took Smith to her home. A dentist gave Smith civilian clothes. Smith traveled to Paris by train with Catherine Janot. Her mother, de Serbonnes, was a law student. A doctor, Jean de Larebeyrette, went ahead to check for German checkpoints. Smith had no French ID.

In Paris, Smith stayed at the de Serbonnes family apartment. On December 15, Catherine Janot asked a Canadian student for help. He sent her to a priest named Michel Riquet. Riquet told Janot that helpers would come for Smith. That evening, Robert Ayle and Andrée de Jongh from the Comet Line met Smith. They checked that he was truly an Allied airman. The next day, de Jongh took Smith to get photos for fake ID papers.

On December 20, Smith left Paris by train with de Jongh, Janine De Greef, and two Belgians. They ate at a restaurant known to the Comet Line. Then they went to a village near the Spanish border. There, they met Francia Usandizanga, a Basque helper. Usandizanga sent 17-year-old Janine de Greef away because it was too dangerous. The next day, December 23, Smith, two other airmen, de Jongh, and a Basque guide, Florentino Goikoetxea, walked across the Pyrenees. They reached San Sebastián, Spain.

In San Sebastián, Smith and the other airmen stayed at Federico Armendariz's house. A British car picked them up. They were driven to Madrid, then to Gibraltar. On January 21, they boarded a ship. They arrived in Scotland on January 26. Smith's rescue went smoothly. But many of the people who helped him later faced terrible consequences. Robert Ayle was executed. Usandizanga died in a German concentration camp. Goikoetxea was shot and wounded. De Jongh and Riquet were sent to concentration camps. Janot had to flee France.

Dangers and Betrayals

In November 1942, the escape routes became much more dangerous. Southern France was taken over by the Germans. All of France was now under direct Nazi rule. Also in November, the German: Abwehr (German military intelligence) struck a big blow. The Maréchal family hid airmen in their home in Brussels. Their house became a meeting place for the Comet Line. Two German agents pretended to be American airmen. They were taken to the Maréchal home. The German: Abwehr then raided the house. They arrested the Maréchals, including 18-year-old Elsie, and many other helpers.

The Germans used the information they got to break the Comet Line in Belgium. One hundred people in Brussels were arrested. On December 1, 1942, the treasurer, Baron Jacques Donny, was arrested at his home. He was betrayed. He was later sentenced to death and executed. He was known as Father Christmas to the airmen because he brought them new clothes.

The next big blow came when Andrée de Jongh was arrested on January 15, 1943. This happened in Urrugne, a French town near the Spanish border. She was probably betrayed by a farm worker. Even though she was questioned many times, the Nazis didn't believe she was a major leader. Dédée, as everyone called her, spent the rest of the war in German prisons and concentration camps. But she survived.

On February 6, 1943, Jean Greindl ("Nemo"), the Comet Line leader in Belgium, was arrested. He was killed in a prison during an Allied air raid. With these losses, the Comet Line stopped operations for February 1943. But in March, they started again. Jean-François Northomb ("Franco") took over from Andrée de Jongh. He became the main escort for airmen to Spain. In June 1943, the Comet Line was hit again. A German spy led the Germans to arrest major leaders in Paris and Brussels. Dédée's father, Frederic ("Paul"), was arrested in Paris on June 7, 1943. He was executed on March 28, 1944.

From the ashes of these arrests, three new leaders emerged. A British agent, Jacques Legrell ("Jerome"), took charge in Paris. Antonie d'Ursel ("Jacques Cartier") restarted the Brussels center. Michelle Dumon ("Michou" or "Lily"), age 22, was a brave and experienced helper. She was the sister of Nadine.

These new leaders didn't last long. On December 24, 1943, d'Ursel ("Jacques Cartier") drowned while crossing the Bidasoa river, which was the border. Legrelle was arrested in Paris on January 17, 1944. Northomb was arrested the next day in the same apartment. Both were tortured but survived the war. As the Allied invasion of Europe approached in June 1944, a working Comet Line was very important. In March 1944, British diplomat Creswell met with Elvire de Greef (Tante Go), Michelle Dumon, and Marcel Roger ("Max"). They planned for a new Comet Line. Roger escorted airmen from Paris to southwestern France. Dumon worked with him in Paris. The de Greef family continued to help with border crossings.

A young Belgian man, Jacques Desoubrie, worked for the Germans. He secretly joined the Comet Line. He was responsible for many arrests. Michelle Dumon exposed him as a German agent in May 1944. The Comet Line had many volunteers. It was hard to check everyone carefully. This made the group vulnerable to German spies.

Hundreds of Comet Line members were betrayed and arrested. They were questioned and tortured in places like Fresnes Prison in Paris. Many were executed. Others were labeled German: Nacht und Nebel (Night and Fog) prisoners. These prisoners were sent to harsh German prisons. Many later went to concentration camps. Women were sent to Ravensbrück concentration camp. Men were sent to Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp, Buchenwald concentration camp, and Flossenbürg concentration camp. Andrée de Jongh, Elsie Maréchal, Andrée Dumon, and Virginia d'Albert-Lake were all sent to these camps.

Comet Line's Impact

Historians say that 2,373 British and Commonwealth soldiers and 2,700 Americans reached Britain using escape lines like the Comet Line. By 1945, about 14,000 helpers worked with many different escape groups. The Comet Line even inspired a 1970s TV show called Secret Army. A window in the Basilica of the Sacred Heart, Brussels honors the Comet Line and the Allied airmen they helped.

Main Routes Used

A common Comet Line route started in Brussels or Lille. From there, it went to Paris. Then, it continued through cities like Tours, Bordeaux, and Bayonne. Finally, it crossed the Pyrenees mountains into San Sebastián in Spain. From Spain, the airmen traveled to Bilbao, Madrid, and then Gibraltar.

Brave Members of the Line

- Kattalin Aguirre: A French Basque widow who helped airmen near the Spanish border.

- Elisabeth Barbier: Worked in Paris, later arrested and sent to Ravensbrück.

- Michael Creswell: A British diplomat in Spain who helped airmen reach Gibraltar.

- Virginia d'Albert-Lake: An American who hid airmen in her Paris home. She survived Ravensbrück.

- Andrée de Jongh (Dédée): Co-creator and first leader. She survived Nazi camps and received the George Medal.

- Frédéric de Jongh (Paul): Dédée's father. He was arrested and executed.

- Elvire De Greef (Tante Go): A key leader in southwestern France. She avoided arrest and survived. Her family also helped.

- Baron Jacques Donny (Father Christmas): The Line's treasurer. He was arrested and executed.

- Michelle Dumon (Michou): A brave and experienced helper who avoided arrest. She received the George Medal.

- Antoine d'Ursel (Jacques Cartier): A leader in Brussels who drowned while crossing the border.

- Florentino Goikoetxea: A Basque smuggler and guide who led many airmen across the Pyrenees. He received the George Medal.

- Miguel Etulain: A 12-year-old Basque child who helped guide airmen to a safehouse.

- Jean Greindl (Nemo): Head of the line in Brussels. He was arrested and killed in an air raid.

- Henriette Hanotte (Monique Hanotte): Helped 140 airmen escape. She received the MBE.

- Albert Edward Johnson ("B"): A British helper who led many airmen across the Pyrenees.

- Jacques Legrelle (Jerome): Organized the line in Paris. He was captured, tortured, and survived. He received the George Medal.

- Elsie Maréchal: British-born, she and her family were captured. They survived concentration camps.

- Jean-François Nothomb (Franco): Succeeded Andrée de Jongh as leader in France. He was arrested and survived. He received the Distinguished Service Order.

- Amanda Stassart (Diane): Captured in 1944 and freed in 1945.

- Rosine Thérier Witton (Rolande): Operated a safe house and served as a guide. She was arrested and survived.

In Books and TV

- Return Journey by Major A. S. B. Arkwright tells the story of three British officers who escaped with the Comet Line.

- Donald L. Miller's Masters of the Air describes the Comet Line's brave young helpers.

- Riding the Comet is a play by Mark Violi. It focuses on a French family helping two American soldiers after D-Day.

See also

- The Nightingale (2015), a fictional book about a French Resistance fighter using a similar escape route.

- Dutch resistance

- Escape and evasion lines (World War II)

- List of networks and movements of the French Resistance

- Secret Army, a BBC television series based on the Comet Line.

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |