Consequences of the attack on Pearl Harbor facts for kids

The attack on Pearl Harbor by Japan on December 7, 1941, was a major event that changed the course of World War II. During this surprise attack, the U.S. military lost 18 ships, which were either damaged or sunk, and about 2,400 people were killed. The most important result of this attack was that the United States officially joined World War II. Before this, the U.S. had been neutral, but after Pearl Harbor, it entered the war in the Pacific, the Atlantic, and Europe. Following the attack, the U.S. also moved many people of Japanese, German, and Italian descent to special camps.

Contents

How Americans Felt Before the Attack

From September 1, 1939, when World War II began, until December 8, 1941, the United States was officially neutral. This was because of laws called the Neutrality Acts, which aimed to keep the U.S. out of wars in Europe and Asia. Before the attack on Pearl Harbor, Americans had different opinions about joining the war.

- Helping the UK: In January 1940, about 60% of Americans wanted to help the United Kingdom in the war. Many believed that the safety of the U.S. depended on the UK winning. They also thought the UK would lose if the U.S. stopped sending war supplies.

- Avoiding War: Even so, 88% of Americans did not want to officially join the war against Germany and Italy. This support for helping the UK grew through 1940, reaching about 65% by May 1941. However, 80% still did not want to go to war with Germany and Italy.

- Regional Differences: Only a few states, mostly in the West and South, favored going to war. For example, over 50% of people in Wyoming said yes to joining the war on Britain's side. Some areas like Tennessee and parts of Georgia were known for being very supportive of Britain.

Americans were also unsure about conflict with Japan. In a February Gallup poll, most people thought the U.S. should get involved in Japan's takeover of the Dutch East Indies and Singapore. But in the same poll, only 39% supported going to war with Japan, while 46% were against it.

Why Japan Attacked Pearl Harbor

On December 8, 1941, Japan declared war on the United States and the British Empire. The Japanese government said they had tried every way to avoid war. They felt the U.S. and UK were causing problems for world peace.

Most Japanese people were surprised and worried by the news of war with the U.S., a country many admired. However, they generally supported their government's reasons for the attack and the war effort until 1945.

- Inevitable War: Japan's leaders believed war with the U.S. had been coming for a long time. Relations had worsened since Japan invaded China in the early 1930s, which the U.S. strongly opposed.

- Japanese Perspective on Provocations: Saburō Kurusu, a former Japanese ambassador, said the war was a response to the U.S.'s long-standing actions against Japan. He mentioned events like the San Francisco School incident, the Naval Limitations Treaty, and economic pressure.

- Oil Embargo: A major reason for Japan's decision was the oil embargo in 1941 by the U.S. and its allies. Japan relied heavily on imported oil, and this embargo severely impacted its economy and military.

- Alliances: These pressures led Japan to ally with Germany and Italy through the Tripartite Pact. Kurusu argued that the Allies had already provoked war with Japan before Pearl Harbor.

- Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere: Japan's leaders felt justified in their actions, believing they were building the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. They claimed the decision to attack was forced upon them. Kurusu stated the surprise attack was not sneaky because it was a direct response to a U.S. demand, the Hull note.

Germany and Italy Join the War

On December 11, 1941, Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy declared war on the United States. The U.S. then declared war back, officially entering the war in Europe.

- No Obligation: German leader Adolf Hitler and Italian leader Benito Mussolini were not required to declare war on the U.S. under their alliance with Japan until the U.S. attacked Japan first.

- Worsening Relations: However, relations between the European Axis Powers and the U.S. had been bad since 1937. The U.S. was already in an undeclared naval war with Germany in the Battle of the Atlantic.

- U.S. Aid: Hitler could no longer ignore the military help the U.S. was giving to Britain and the Soviet Union through the Lend-Lease program.

- Underestimation: Hitler badly underestimated America's ability to produce military goods and fight on two fronts. He also thought his own war in the Soviet Union would be quicker.

- Soviet-Japanese Relations: The Nazis hoped their declaration of war would lead to closer cooperation with Japan against the Soviet Union. However, Japan had a neutrality pact with the Soviets and did not plan to attack them.

The decision by Germany and Italy to declare war on the U.S. allowed the United States to join the war in Europe to support the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union without much public disagreement.

Britain's Reaction to the Attack

The United Kingdom declared war on Japan nine hours before the U.S. did. This was partly because Japan also attacked British colonies like Malaya, Singapore, and Hong Kong. It was also because Prime Minister Winston Churchill had promised to declare war "within the hour" if Japan attacked the United States.

- Difficult Times for Britain: The war had been going poorly for the British Empire for over two years. The UK was the only major country in Western Europe not taken over by the Nazis.

- Churchill's Relief: Churchill had long tried to convince America to join the war against the Nazis. He was often turned down by Americans who believed the war was only a European problem. When he heard about the Pearl Harbor attack, Churchill immediately understood its huge impact. He felt a great sense of relief.

Churchill later wrote about his feelings, saying that Britain and its empire would survive. He believed that Hitler and Mussolini's fates were sealed, and Japan would be crushed. He felt that victory was now certain.

Investigating the Attack

After the attack, President Roosevelt created the Roberts Commission to investigate what happened at Pearl Harbor. This was the first of nine official investigations.

- Commanders Relieved: The Navy commander, Rear Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, and the Army commander, Lieutenant General Walter Short, were removed from their positions. They were accused of not preparing enough defenses.

- Controversy: The decision to relieve them was controversial then and still is today. However, they were not put on trial, which would normally happen for such accusations.

- Exoneration: In 1999, the U.S. Senate voted to recommend that both officers be cleared of all charges. They stated that the commanders were not given important information that was available in Washington.

- Congressional Investigation: A special committee of Congress was also formed in 1945 to investigate the causes of the attack.

Impact of the Attack and Its Meaning Today

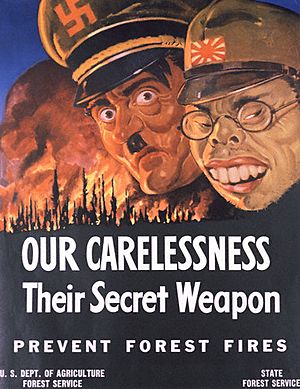

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, along with their alliance with the Nazis, led to strong anti-Japanese feelings in the Allied nations. People of Japanese, Japanese-American, and other Asian backgrounds were viewed with deep suspicion. The attack was seen as very "treacherous" or "sneaky."

- Internment: The fear of spies and the anger over the attack led to the moving of Japanese, German, and Italian people into special camps in the U.S. and Canada.

- World-Changing Consequences: The attack started the Pacific War, which ended with Japan's surrender. This war led to the U.S. becoming a major world power, which has shaped international politics ever since.

- Historical Significance: Pearl Harbor is seen as an extraordinary event in American history. It was the first time since the War of 1812 that America was attacked on its own land by a foreign power. Only the September 11 attacks almost 60 years later were of a similar scale.

How People See the Attack Today

Some Japanese people today feel they were forced to fight because their national interests were threatened. They point to the oil embargo imposed by the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands. Japan's navy and economy depended heavily on imported oil.

- Comparing Casualties: Japanese writers often compare the thousands of U.S. citizens killed at Pearl Harbor to the hundreds of thousands of Japanese civilians killed in U.S. air attacks during the war, including the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945.

- Flawed Strategy: Many Japanese also believe that while the Pearl Harbor attack was a good tactic, it was part of a flawed strategy against the U.S. They thought Japan's strong spirit could overcome America's material wealth, but this proved wrong.

- Declaration Delay: In 1941, the Japanese Foreign Ministry said Japan intended to declare war 25 minutes before the attack. However, due to delays, the Japanese ambassador could not deliver the message until after the attack had begun.

- Mixed Feelings: Japanese military leaders had mixed feelings. Fleet Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto was unhappy about the delayed declaration. He had said earlier that Japan could "run wild for six months" but expected no success after that. He also wondered if Japanese politicians understood the sacrifices needed for a war with the U.S.

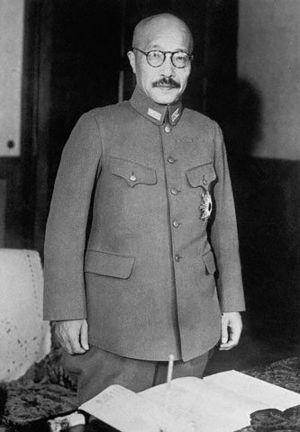

The Prime Minister of Japan during World War II, Hideki Tōjō, later wrote that the surprise success of the Pearl Harbor attack seemed like "a blessing from Heaven."

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |