Continuation War facts for kids

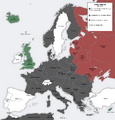

The Continuation War is the name for the war between Finland and the Soviet Union from June 26 1941 to September 19th 1944. It is named thus since the Finns see it as a continuation of the Winter War and the numerous threats against Finland during the peace that followed.

Finland's principal goal during World War II was, although nowhere literally stated, to survive the war as an independent country, capable to mind its own businesses in a politically hostile environment. It must be noted that Finland's exertion in this respect was successful, although the price most certainly was high counted in war casualties, pecuniary tribute, territorial loss, bruised international reputation and reverential adaptations to the Soviet Union.

The war was formally concluded by the Paris peace treaty of 1947.

Contents

Background

After the peace agreement of the Winter War, Finland was bent on getting back at the Soviet Union. The public opinion longed for the re-aquisition of the homes for the 10% of the population who had been forced to leave Karelia in haste after the armistice, expecting the injustice to be corrected at the big peace conference awaited after World War II. Then there was a vociferous minority opinion advocating the protection of the ethnically akin Finnic peoples under Soviet oppression by extending Finland's territory eastwards. Notably in the latters' opinion, Finland's security politics focusing on Scandinavia (particularly Sweden), the League of Nations and the politically akin democratic Western countries had led to a total fiasco.

The experience from World War I emphasized the importance of close and friendly relations with the victors, why Nazi-Germany was intensely courted immediately after the Winter War, when Germany had been the ally of the aggressive Soviet Union. Finland got a new Cabinet with a Foreign Minister, Rolf Witting, more in the taste of the Nazis, and a new energetic ambassador in Berlin, Toivo Mikael Kivimäki. From August 18th 1940 Finland secretly negotiated with Germany on military cooperation, buying artillery and other badly needed weapons from Germany, which until then had been impossible in reverence of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. Finland in return facilitated German troop transfers to Finnmark in Northern Norway (occupied by Germany since June-July 1940). Through the potential presence of German troops on Finnish territory Finland intended to deter the Soviet Union from planing further military assaults, as that then would threathen to involve Germany on the side of Finland's.

This secret Finno-German agreement was in material breach of the peace treaty of the Winter War, which in fact was chiefly targeted against cooperation between Germany and Finland. It has in retrospect been disputed whether the diseased President Kallio was informed. Possibly the responsibility was taken by the then-premier Risto Ryti in concert with Field Marshal Mannerheim.

Adolf Hitler had not been interested in Finland before the Winter War. Now he saw the value of Finland as a staging base for his forthcoming invasion of the Soviet Union, and maybe also the military value of the Finnish army. The informal German-Finnish agreement of August 1940 was formalized in September. It allowed Germany the right to send its troops by trucks and busses through Finland, ostensibly to facilitate Germany's reinforcement of its forces in northern Norway. A further German-Finnish agreement in December 1940 led to the stationing of German troops in Finland (mainly in the vicinity of the northern border to the Soviet Union) and in the coming months they arrived in increasing numbers, establishing quarters, depots and bases along the road to Norway, which later would be used for the concentration of troops aimed for Northern Russia. Although the Finnish people knew only the barest details of the agreements with Germany, they approved generally of the pro-German policy. Especially the Karelians wanted to recover the ceded territories.

Coordination with Germany

By the spring of 1941, the Finnish military was aware of the German plans for the invasion of Russia, although no-one could feel sure of Hitler's real intentions. An uncertainty still prevailed as to whether Hitler really intended to attack the Soviet Union before Great Britain was conquered. Perhaps the build-up aimed only at applying pressure - not a two-front war. In that case Finland was a possible token of reconsiliation between Hitler and Stalin, which the Finns had every reason to fear.

In 1941 the German army's standing was in zenith. Germany's final victory, and Europe's adaption to German hegemony, seemed unavoidable. Race issues were reasons of particular concerns: The Finns were not viewed favorably by the Nazi race theorists. By active participation on the side of Germany's, Finland could hope for a more independent position in post-war Europe, at the same time as the Soviet threat was definitively taken care of, and the akin Finnic peoples of the neighbourhood could be granted the advantage of inclusion in Finland. This view gained increasing popularity in the Finnish leadership, and also in the press, during the preparations for the awaited outburst between Germany and the Soviet Union.

What began for the Finns as a defensive strategy, designed to provide a German counterweight to Soviet pressure, ended as an offensive strategy, aimed at invading the Soviet Union. The Finns had been lured by the prospects of regaining their lost territories and ridding themselves of the Soviet threat.

Outbreak of the war

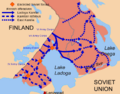

The signs and rumours of the German assault on Russia heaped up, and on June 9th partial mobilization was ordered, and the northern Finish air defense troops consisting of 30,000 men were put under German command. In practice Germany already held the northern half of the border to Russia. On June 14th also the 3rd Army Corps was mobilized and put under German command. On June 17th general mobilization took place. On June 20th Finland's government ordered 45,000 people at the Soviet border to be evacuated. Finally, on June 21st, Germany officially informed Finland's General Staff chief, general Erik Heinrichs, that the German attack was under way.

The Finnish government did not want to appear as the aggressor, why Finland took no part in the German invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22th. (Hitler's public statement gave another impression. Hitler declared Germany to attack the Bolshevists "in the North, in alliance (im Bunde) with the Finnish freedom heroes".) Three days later, Soviet bombing against Finland (for instance the towns of Porvoo, Turku and Helsinki, partially incendiary bombs on wooden residential areas) gave the Finnish government the pretext needed to open hostilities, and war was declared on June 26th.

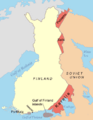

July 10th 1941, the Finnish army began a major offensive on the Karelian Isthmus and north of Lake Ladoga. Mannerheim's order of the day clearly states that the Finnish involvement was an offensive one. By the end of August 1941, Finnish troops had reached the prewar boundaries. The trespassing of the pre-war borders led to tensions in the armed troops, in the Cabinet, in the parties of the parliament, in the domestic opinion. The expansionism might have gained popularity, but it was far from unanimously championed.

In particularly international relations were strained - notably with Sweden and Britain, whose governments in May and June in confidence had learned from Foreign Minister Witting that Finland had absolutely no plans for a military campaign coordinated with the Germans. Finland's preparations were said to be purely defensive. Sweden's leading Cabinet members had hoped to improve the relations with Germany through indirect support, canalized via Finland. The political support in Sweden turned however out to be insufficient, particularly after Mannerheim's infamous order of the day, and even more so after Finland had commenced a war of conquest. A tangible effect was that Finland hereby became dependent on food, munition and arms supply from Germany.

In December 1941, the Finnish advance had reached the outskirts of Leningrad and the Svir River (which connects the southern ends of Lake Ladoga and Lake Onega). By the end of 1941, the front became stabilized, and the Finns did not conduct major offensive operations for the following two and a half years.

Diplomatic manoevres

Germany's eastern campaign was planned as a blitzkrieg lasting a few weeks. Also British and US observers believed the attack to be concluded before August. In the autumn 1941 this turned out to be wrong, and leading Finnish militaries started to mistrust Germany's capacity. Finland's strategy now changed. A separate peace with the Soviet Union was offered, but Germany's strength was far too terrifying. Finland had to continue the war for some time, putting the own forces at the least possible danger, and hoping that the Wehrmacht and the Red Army meanwhile would mince eachother.

Finland's participation in the war brought major benefits to Germany. The Soviet fleet was blockaded in the Gulf of Finland, so that the Baltic was freed for training German submarine crews as well as for German shipping, especially for the vital iron ore from northern Sweden and nickel from the Petsamo area. The sixteen Finnish divisions tied down numerous Soviet troops, put pressure on Leningrad - although Mannerheim refused to attack - and threatened the Murmansk Railroad. Sweden was further isolated and was increasingly pressured to comply with Finnish and German wishes, although with limited success.

Despite Finland's contributions to the German cause, the Western Allies had ambivalent feelings, torn between residual goodwill for Finland and the need to accomodate their vital ally, the Soviet Union. As a result, Britain declared war against Finland, but the United States did not. There was no combat between these countries and Finland; but Finnish sailors were interned overseas. In the United States, Finland was highly regarded, because it had continued to make payments on its World War I debt faithfully throughout the interwar period. Finland later also earned respect in the West for the strength of its democracy and its refusal to allow extension of Nazi anti-Semitic practices in Finland. Finnish Jews served in the Finnish arm, and Jews were not only tolerated in Finland, but most Jewish refugees also were granted asylum.

The end of the war

Finland began to seek a way out of the war after the disastrous German defeat at Stalingrad in January-February 1943. Edwin Linkomies formed a new cabinet with the peace process as the top priority. Negotiations were conducted intermittently between Finland and its representative Juho Kusti Paasikivi on the one side and the Western Allies and the Soviet Union on the other, from 1943 to 1944, but no agreement was reached.

Instead, in June 1944, the Soviet Union opened a major offensive against Finnish positions on the Karelian Isthmus and in the Lake Ladoga area. On the second day of the offensive, the Soviet forces broke through the Finnish lines, and in the succeeding days they made advances that appeared to threaten the survival of Finland. Finland clearly needed more weapons and ammunition, which the Nazi Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop offered in exchange of guarantees that Finland would not again seek a separate peace. President Risto Ryti gave his guarantee, by Ryti intended to last for the remainder of his presidency.

With new supplies from Germany, the Finns were now equal to the crisis, and halted the Russians in early July 1944, after a retreat of about one hundred kilometers that brought them approximately to the 1940 boundaries. Finland had already become a sideshow for the Soviet leadership, which now turned their attention to Poland and to the Balkans. Although the Finnish front was once again stabilized, the Finns were exhausted and wanted to get out of the war. President Risto Ryti resigned, and Finland's military leader and national hero, Carl Gustaf Mannerheim, became president, accepting the responsibility for ending the war.

September 19th 1944, an armistice (practically a preliminary peace treaty) was signed in Moscow between the Soviet Union and Finland. Finland had to sign many limiting consessions: The Soviet Union regained the borders of 1940, with addition of the Petsamo area. The Porkkala Peninsula (adjacent to Finland's capital Helsinki) was leased to Soviet for fifty years, and transit rights were granted. Finland's army was to demobilize in haste. And Finland was required to expel all German troops from its territory. As the Germans refused to leave Finland voluntarily, the Finns were forced to fight their former allies in the Lapland war.

Finland had not won, how would that have been possible against a nation nearly 100 times as big, but it had managed to avoid the total occupation and the highly probable following annihilation. A major goal of post-war Finnish foreign policy was to keep it that way.

Images for kids

-

Finnish flags at half-mast in Helsinki on 13 March 1940 after the Moscow Peace Treaty became public

-

Vasilievsky Island in Saint Petersburg, pictured in 2017. During the Winter and Continuation Wars, Leningrad, as it was then known, was of strategic importance to both sides.

-

Joachim von Ribbentrop (right) bidding farewell to Vyacheslav Molotov in Berlin on 14 November 1940 after discussing Finland's coming fate

-

President Risto Ryti giving his famous radio speech about the Continuation War on June 26, 1941.

-

A Finnish soldier with a reindeer in Lapland. Reindeer were used in many capacities, such as pulling supply sleighs in snowy conditions.

-

Keitel (left), Hitler, Mannerheim and Ryti meeting at Immola Airfield on 4 June 1942. Hitler made a surprise visit in honour of Mannerheim's 75th birthday and to discuss plans.

See also

In Spanish: Guerra de Continuación para niños

In Spanish: Guerra de Continuación para niños