Cumberlandian combshell facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Cumberlandian combshell |

|

|---|---|

|

|

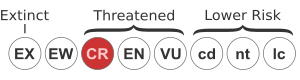

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Bivalvia |

| Order: | Unionida |

| Family: | Unionidae |

| Genus: | Epioblasma |

| Species: |

E. brevidens

|

| Binomial name | |

| Epioblasma brevidens (I. Lea, 1831)

|

|

|

|

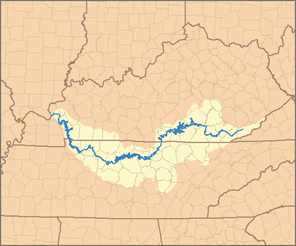

| The Cumberland River | |

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Dysnomia brevidens I. Lea, 1831 |

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The Cumberlandian combshell (Epioblasma brevidens) is a special type of freshwater mussel. Mussels are bivalves, which means they have two shells that open and close. They are a kind of mollusk, like snails and clams.

This mussel lives only in the United States, mostly in Tennessee and Virginia. You can find them in medium-sized streams and large rivers. The combshell is an endangered species, which means it's protected by law, like the Endangered Species Act of 1973. Its biggest threats are changes to its home and water pollution.

Contents

What Does It Look Like?

The Cumberlandian combshell is a brown and yellow mussel. It grows to be about two inches (5.1 cm) long. Its shell has a thin, film-like coating that is yellow and brown. You can also see many green stripes, called rays, on its shell. The inside of the mussel's shell is a shiny pearl-white color.

Female combshells have special teeth-like bumps around the edge of their shell. Their shells also look a bit puffy. These mussels live in groups, often in areas with coarse sand, gravel, and large rocks in rivers. They usually prefer water less than three feet (0.91 m) deep. However, they can sometimes be found in deeper spots, like in the Old Hickory Reservoir on the Cumberland River.

Combshells are filter feeders. This means they get their food by filtering tiny bits from the water. They eat things like bacteria, diatoms (tiny algae), phytoplankton (tiny plants), zooplankton (tiny animals), and other small particles.

How It Lives

Life Cycle

Young combshells are called "suspension/deposit feeders." This means they let water flow through their gills to get food, but they don't actively pump it. They also use tiny hairs on their feet to pull in food particles. They eat many tiny living things in the streams and rivers.

As they grow into adults, mussels become "filter feeders." They actively pump water to get oxygen and food. Both young and adult mussels eat bacteria, algae, diatoms, and other tiny particles. Adult mussels also eat phytoplankton, zooplankton, and other organic material in the water.

Female combshells take care of their eggs for a long time, usually from late summer to late spring. The eggs grow inside special parts of the mussel's gills, called "marsupia." These eggs then turn into tiny, parasitic larvae called "glochidia."

Reproduction

When they are ready, the glochidia attach themselves to the gills or fins of different types of fish. This is how they finish growing into young mussels. They attach to several native fish species, including different kinds of darter fish and sculpins.

Female mussels produce many larvae, but only a few find a fish host. Even fewer survive to become adult mussels. This means that combshells need healthy fish populations to survive and reproduce.

Where It Lives and How Many There Are

Habitat

The Cumberlandian combshell likes medium-sized streams and large rivers. It's rare to find them in small streams. In these waterways, they live in coarse sand, gravel, cobble (small rounded stones), and boulders. They prefer water that is three feet deep or less, but they can also be found in deeper, fast-flowing waters like the Old Hickory Reservoir.

Important Habitats

The U.S. government has named certain places as "critical habitat" for combshells. This means these areas are very important for the mussel's survival and recovery. These special places include:

- Three streams in the Cumberland River area:

* Buck Creek in Pulaski County, Kentucky * Big South Fork in Scott County, Tennessee, and McCreary County, Kentucky

- Seven streams in the Tennessee River area:

* Clinch River in Scott County, Virginia (where they are most common) and Hancock County, Tennessee * Powell River in Lee County, Virginia, and Claiborne/Hancock counties, Tennessee * Bear Creek in Colbert County, Alabama, and Tishomingo County, Mississippi

Historical and Present Populations

In the past, the Cumberlandian combshell was found in many places across Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Virginia. They lived in different types of landscapes, including plateaus and valleys. In the 1940s, they were "very common" in the upper Cumberland River. However, by 1980, they were considered "extremely rare."

Today, you can only find small numbers of combshells in Northeast Mississippi and Southwest Virginia. Most of the remaining mussels are in Tennessee and Kentucky, in the Cumberland and Tennessee River basins.

There are no exact numbers for how many combshells existed in the past. But we know they were once "very common." Now, most of the populations in the main rivers are gone. Threats have caused their numbers to drop greatly. Today, they are found in only 5 rivers, compared to their much larger historical range.

In the 1980s, studies found only about 0.01 to 0.03 mussels per square foot in some areas. Current populations are so small that their genetic diversity is at risk. This can make them more likely to get sick or struggle to adapt to changes.

Some waterways, like the Clinch River, Powell River, and the Big South Fork National River, seem to have stable populations. But this is not true for all areas. Scientists are working to help. For example, in 2016, a fish hatchery raised 521 combshells to release into rivers. This more than doubled the number believed to be in the Big South Fork of the Cumberland Rivers. In 2017, 706 more mussels were released. Scientists also tag and track mussels to learn about their survival and growth.

Threats and Conservation Efforts

Major Threats

Small Population Size

Having very few individuals puts the combshell at high risk of disappearing forever. Also, the remaining groups of mussels are far apart. This means they can't easily reproduce with each other, which reduces their genetic diversity. This makes it harder for them to adapt to new challenges, whether natural or caused by humans.

Water Pollution

Many combshell populations were lost when dams were built on the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers starting in 1971. Combshells cannot survive in waters changed by dams. Dams permanently change the free-flowing water that mussels and their host fish need.

Other populations were lost because of water pollution and siltation (when too much dirt and sand build up). The combshell is especially sensitive to pollution from coal mining and poor land use. As cities grow, pollution from many different sources, called nonpoint sources, has also increased. Combshell populations are also at risk from natural events like toxic chemical spills.

Fish Host Decline

The same threats that harm the combshells also affect the fish they need for their young to grow. If fish populations decline, it becomes harder for the combshells to reproduce successfully.

Invasive Species

One of the biggest threats to the combshell is an invasive species called the zebra mussel (Dreissena polymorpha). Zebra mussels came from lakes in southern Russia and Ukraine and arrived in North America in 1988. Zebra mussels compete with Cumberlandian combshells for the same food and space, putting more pressure on the already threatened combshells.

Human Impacts and Conservation

Humans have caused a lot of habitat loss for the Cumberlandian combshell. Things like building dams, channelizing rivers (making them wider or deeper), water pollution, and sedimentation (dirt runoff) have all harmed their homes.

However, people are now working to fix these problems. Listing the combshell as an endangered species gives it legal protection, which should help it recover. A recovery plan has been created for the combshell, even though it's part of a plan for several species. The combshell was first listed as threatened in 1991 and then endangered in 1997. Its recovery plan was put in place in 2004.

The combshell also has "designated critical habitat." This means no development is allowed that would harm these important areas. The species has also had reviews in 2005 and 2018 to track how conservation efforts are helping its populations.

Endangered Species Act Listing

The Cumberlandian combshell was officially listed as endangered in 1997 under the Endangered Species Act of 1973. The Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) decided this because the mussel's range and population numbers had dropped so much. It was first considered for protection in 1991, but the final decision came on January 10, 1997.

At first, the FWS didn't plan to name critical habitats, but they did so in 2004. These habitats include the Duck River in Tennessee, Bear Creek in Alabama and Mississippi, Powell River in Tennessee and Virginia, Clinch River in Tennessee and Virginia, Nolichucky River in Tennessee, Big South Fork in Tennessee and Kentucky, and Buck Creek in Kentucky.

Conservation scientists first put combshells on a list of possibly endangered or threatened species in 1984. They were listed again in 1989 and 1991. By 1994, scientists suggested the combshell should be legally endangered. Today, they are considered critically endangered.

Changes to rivers, like building dams and mining, have hurt combshell populations. Other threats, like losing their habitat and pollution, also harm them. Since combshells depend on fish, changes in fish populations also affect them.

Current Conservation Efforts

The recovery plan for the Cumberlandian combshell says the species can be removed from the endangered list when healthy populations are found in at least nine streams. Currently, they are found in only five. The plan stresses that managing the whole ecosystem (all the living things and their environment) is the best way to protect many species, not just one. The Freshwater Mollusk Conservation Society was created to help protect mussels.

The Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources Center for Mollusk Conservation raises combshells to release them back into their natural habitat.

Scientists are also doing studies to find out exactly where combshells live and how many there are. For example, studies were submitted in 2019 and 2020 to check for combshells in the Big South Fork National River and other states.

The Fish and Wildlife Service suggests ways everyday people can help, such as:

- Limiting the use of pesticides.

- Planting trees to stop soil from washing into rivers.

- Saving energy to prevent the need for new hydroelectric power plants.

- Cleaning aquatic weeds from boat trailers and engines to stop the spread of invasive species.

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |