Cândido Rondon facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Cândido Mariano da Silva Rondon

|

|

|---|---|

Marshal Rondon in 1930

|

|

| Birth name | Cândido Mariano da Silva |

| Nickname(s) | Marshal Rondon |

| Born | May 5, 1865 Santo Antônio do Leverger, Mato Grosso, Empire of Brazil |

| Died | January 19, 1958 (aged 92) Rio de Janeiro, Federal District, Brazil |

| Buried |

Cemitério de São João Batista, Rio de Janeiro

|

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1881–1955 |

| Rank | |

| Commands held | Military Corps of Engineers Strategic Telegraph Lines Commission Indian Protection Service |

| Battles/wars | Proclamation of the Republic Revolta da Armada Revolution of 1930 |

| Awards | David Livingstone Centenary Medal Explorers Club Medal Order of Columbus |

| Spouse(s) | Francisca "Chiquinha" Xavier (m. 1896) |

| Other work | Author, Engineer |

| Signature | |

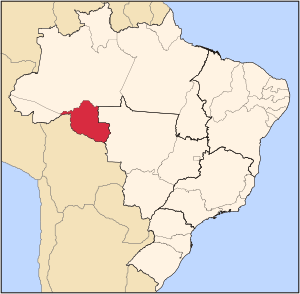

Cândido Mariano da Silva Rondon (born May 5, 1865 – died January 19, 1958) was a famous Brazilian military officer. He is best known for building telegraph lines and exploring the vast regions of Mato Grosso and the western Amazon basin. Rondon also spent his life supporting the indigenous people of Brazil.

He was the first head of Brazil's Indian Protection Service (SPI). He also helped create the Xingu National Park. The Brazilian state of Rondônia is named after him.

Contents

Biography

Early life and military career

Cândido Mariano da Silva was born on May 5, 1865, in Mimoso, a small village in Mato Grosso. His father died before he was born, and his mother passed away when he was two. He was raised by his grandparents and then by his uncle, Manuel Rodrigues da Silva Rondon, whose last name he later adopted.

At 16, Rondon finished high school and taught for two years. In 1881, he joined the Brazilian army. He studied math and sciences at officer's school, graduating in 1888. He was also involved in the movement that led to Brazil becoming a republic, ending the rule of the last Emperor of Brazil, Pedro II of Brazil.

Building telegraph lines

In 1890, the new Brazilian government asked Rondon to help build the first telegraph line across Mato Grosso. This was important because western Brazil was very isolated. The line was finished in 1895. After that, Rondon began building a road from Rio de Janeiro (then the capital) to Cuiabá, the capital of Mato Grosso. Before this road, people could only travel between these cities by river.

Rondon married Francisca (Chiquinha) Xavier, and they had seven children. From 1900 to 1906, he oversaw laying telegraph lines from Brazil to Bolivia and Peru. During this time, he explored new areas and met the Bororo people. He was so good at making peaceful contact with them that they even helped him finish the telegraph line. Throughout his life, Rondon laid over 4,000 miles (6,400 km) of telegraph lines through Brazil's jungles.

Rondon was later honored as the "Patron of the Communications Corps of the Brazilian Army."

Later achievements

After a big expedition with Theodore Roosevelt in 1914, Rondon spent time mapping the state of Mato Grosso. He discovered more rivers and met several indigenous tribes. In 1919, he became the chief of the Brazilian Corps of Engineers and head of the Telegraphic Commission.

From 1927 to 1930, Rondon was in charge of surveying Brazil's borders with its neighboring countries. He also helped solve a border dispute between Colombia and Peru. In 1939, he returned to lead the Indian Protection Service (SPI), expanding its work to new parts of Brazil.

In the 1950s, he supported the Villas-Bôas brothers in their efforts to protect indigenous people. This led to the creation of the Xingu National Park in 1961, Brazil's first national park for indigenous communities along the Xingu River.

On his 90th birthday in 1955, Rondon was given the highest military rank: Marshal of the Brazilian Army. In 1957, he was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize. He passed away in 1958 in Rio de Janeiro at the age of 92.

The Rondon Commission

Cândido Rondon led a large military project to extend telegraph lines into the Brazilian Amazon. This group was also known as "The Rondon Commission." Rondon believed his work would help unite all people in Brazil. He thought that progress should happen quickly and that indigenous people should become part of modern society in a peaceful way. He wanted to "guide" them to a more "civilized" life.

However, some people believe that Rondon's main goal was military. They think the mission was mostly about marking Brazil's borders for defense and creating new areas for people to settle and for businesses to grow. This view suggests that Rondon was not just a hero of peace and unity for indigenous tribes.

The Rondon Commission did help open up the Amazon for economic growth. Many new towns appeared along the telegraph lines. New settlers wanted land for farming and ranching. But this also meant that indigenous tribes, like the Bororo, were often forced to move from their homes.

Explorations

Rondon was very skilled at building telegraph lines. Because of this, he was put in charge of extending the lines from Mato Grosso into the Amazon. While building the line, he mapped the Juruena river. He also made peaceful contact with the Nambikwara tribe, who had previously not welcomed outsiders.

In 1911, he visited the ruins of the old Forte Príncipe da Beira, a historic fort in what is now Rondônia. He was promoted to major in the military engineers. His work from 1907 to 1915 was called the "Rondon Commission." At the same time, the Madeira-Mamoré Railroad was being built. Both projects helped people settle the region that is now the state of Rondônia.

In May 1909, Rondon began his longest expedition. He traveled from Tapirapuã in northern Mato Grosso northwest to meet the Madeira River, a major tributary of the Amazon River. By August, his team had run out of food and had to hunt and gather from the forest. When they reached the Ji-Paraná River, they had no supplies left. During this trip, they discovered a large river between the Juruena and Ji-Paraná rivers, which Rondon named the River of Doubt. To reach the Madeira, they built canoes and arrived on Christmas Day, 1909.

When Rondon returned to Rio de Janeiro, he was celebrated as a hero. Many people thought he and his expedition had died in the jungle. After this journey, he became the first director of the Brazilian Government's Indian Protection Agency, the SPI.

In September 1913, Rondon was hit by a poisoned arrow from the Nambikwara Indians. In 1914, his commission built 372 km (231 miles) of lines and five more telegraph stations in the area of present-day Rondônia. On January 1, 1915, he finished his mission by opening the telegraph station in Santo Antônio do Madeira.

Rondon was the second person in history to have a meridian (a line of longitude) named after him. He opened roads, cleared land, laid telegraph lines, mapped the country, and built good relationships with indigenous people.

Expedition with Roosevelt

In January 1914, Rondon joined former U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt on the Roosevelt-Rondon Scientific Expedition. Their goal was to explore the River of Doubt. The expedition reached the river on February 27, 1914. They did not reach the end of the river until late April, after facing many difficulties. During this journey, the river was renamed the Rio Roosevelt.

Roosevelt later said that going down the River of Doubt was the hardest adventure of his life. Most of the men on the expedition, except Rondon, suffered from illnesses.

Positivism and Rondon's beliefs

From 1898 onwards, Rondon was a strong follower of the Igreja Positivista do Brasil (Positivist Church of Brazil). This religion was based on the ideas of Auguste Comte. It focused on science, nature, and helping others, rather than on supernatural forces.

Positivism aimed to prevent social problems by encouraging different groups in society to work together. Comte believed that human society goes through three stages of development. He emphasized scientific thinking, industry, modernization, and general improvements. These ideas became popular in Brazil after the Paraguayan War (1865–1870), when many Brazilians questioned their society.

Rondon first learned about positivism in 1885 as a student at the Military Academy in Rio de Janeiro. He became a passionate lifelong member of the Positivist Church. He believed that Brazil, and the world, would eventually accept positivism because it was so logical.

Positivism shaped Rondon's views on life, how different races should interact, and his plans for Brazil's development. He once told his men that he wanted to create a "political utopia." He believed his telegraph line helped humanity evolve because it brought him into contact with many tribes for the first time. However, Rondon's positivism sometimes caused disagreements with the more powerful Catholic Church, which limited the long-term impact of his work.

The Indian Protection Service (SPI)

In 1910, Rondon was asked to be the first leader of the Serviço de Proteção ao Índio (SPI), Brazil's Indian Protection Service. He told the Minister of Agriculture that his positivist beliefs would guide his work with the organization. He believed that instead of forcing indigenous people to change through Christian missionaries, it was better to gently guide them into the modern world by setting an example. Rondon and other Positivists argued for protecting indigenous people and their lands. They said that these groups were not less capable, but simply at an earlier stage of positivist development.

Rondon led the SPI until the Brazilian Revolution of 1930. Many of his original plans remained ideas. The SPI's goal was to protect the well-being of native people. Rondon created its motto: "die if need be, never kill." Reports from as late as 1960 claimed that the SPI had met its goals without breaking this motto. They even said that despite some SPI members being killed by poisoned arrows, they never killed an indigenous person. Instead, they used peaceful methods to encourage tribes to interact with them.

However, shortly before Rondon's death in 1958, serious problems were discovered. There were reports of corruption and abuse of indigenous people by some working with the SPI. The organization was closed down in 1967. A similar organization, Fundação Nacional do Índio (FUNAI), took its place later that year.

Homages

Marshal Cândido Rondon is seen as one of Brazil's greatest heroes. He has been honored in many ways by the people and government. He is known as the "Father of Brazilian Telecommunications," and May 5th is celebrated as the National Day of Telecommunications in his honor. His name was also written in a special book at the Geographical Society of New York.

Many places and things are named after him, including:

- The state of Rondônia

- The Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul

- Several municipalities (cities), such as Rondon in Pará, Marechal Cândido Rondon in Paraná, Marechal Rondon in Mato Grosso, and Rondonópolis in Mato Grosso.

- Faculdades Integradas Cândido Rondon in Cuiabá, Mato Grosso.

- Project Rondon, a program for students to help communities.

- Museu Rondon at the Federal University of Mato Grosso.

- Marechal Rondon Library in Rio de Janeiro.

- Bosque Municipal Marechal Rondon in Londrina, Paraná.

- Marechal Rondon International Airport in Cuiabá/Várzea Grande, Mato Grosso.

- Marechal Rondon Highway in the State of São Paulo.

- Several animals, including Rondon's marmoset (a small monkey), Rondon's tuco-tuco (a rodent), and Rondon's gymnophthalmid (a type of lizard).

Thousands of streets, schools, and other places also carry Rondon's name.

See also

In Spanish: Cândido Rondon para niños

In Spanish: Cândido Rondon para niños

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |