Dare Stones facts for kids

The Dare Stones are a group of stones with messages carved into them. People believed these messages were written by members of the Roanoke Colony, also known as the "Lost Colony." These stones were supposedly found in the southeastern United States in the late 1930s. The colonists were last seen on Roanoke Island in what is now North Carolina in August 1587. The mystery of their disappearance has become a famous part of American stories. When the stones were found, they caused a lot of excitement. Everyone wanted to know if they would finally solve the mystery of the Lost Colony.

There are 48 Dare Stones kept at Brenau University in Gainesville, Georgia. Some other stones were also reported. Most of the messages on the Brenau stones claim to be from Eleanor Dare. She was a Lost Colonist and the daughter of the colony's governor, John White. John White had gone back to England in 1587. When he returned three years later, all the colonists were gone. The messages on the stones tell a story about what happened to the colonists between 1591 and 1603. They suggest the colonists moved from Roanoke to the Chattahoochee River Valley near Atlanta.

The first stone was reported in 1937 by Louis E. Hammond. He said he found it near the Chowan River. The message on this stone mentioned another stone that marked a mass grave. This made people search very hard for more stones. The other 47 stones at Brenau looked very different. They were all linked to a stonecutter named Bill Eberhardt from Georgia. These stones were later found to be fake. By 1941, experts and news reporters said all the Dare Stones were hoaxes. However, no one has ever fully proven or disproven if Hammond's first stone was real or fake.

Contents

What Was the Lost Colony?

The "Lost Colony" was England's second try at building a settlement in North America. The first attempt in 1585, led by Ralph Lane, had failed. The new group of colonists arrived at Roanoke in July 1587. John White was their leader, or governor. They originally planned to go to Chesapeake Bay. But the ship's crew would not take them any further than Roanoke.

The first colony had problems with the local Secotan tribe. This made Roanoke a dangerous place for a new settlement. However, White's group was able to make friends with the Croatan tribe on nearby Croatoan Island. White said the settlers had already talked about moving "50 miles further up into the maine." This meant moving closer to the Chowan River near Albemarle Sound.

When the ships were leaving in August, the colonists asked White to go back to England. They wanted him to arrange for more supplies to be sent. They expected White to return the next year. But the war between England and Spain delayed him until 1590. When he finally returned, the Roanoke settlement was gone. It was empty and surrounded by fences. White found the word "CROATOAN" carved into a fence post. But bad weather stopped him from following this clue. Later searches in the area were also difficult because of storms and dangerous waters.

In 1612, a writer named William Strachey said that the Lost Colonists were killed. He claimed the Powhatan tribe attacked them just before the Jamestown colony started in 1607. According to this story, the Powhatan leader, Wahunsenacawh, was warned by his priests. They said a group would rise from the Chesapeake Bay and threaten his tribe. So, he ordered the attack to stop this prophecy.

Strachey also reported that seven colonists survived. These were four men, two boys, and a young woman. They supposedly fled up the Chowan River. Another tribe captured them and kept them in a place called "Ritanoe." There, they were forced to work with copper. Many people believed Strachey's theory in the mid-to-late 1900s. But historians now question if his sources were fair. They also wonder if he had reasons to speak badly about Wahunsenacawh. Most Americans in the 1930s would not have known these details of Strachey's story.

The story of the Lost Colony became very popular in the United States. This happened after several exciting accounts were published in the 1830s. Eleanor Dare's daughter, Virginia Dare, became a famous symbol. She was the first English child born in the New World. Celebrations of her birthday became a big tourist event in North Carolina. In 1937, a play called The Lost Colony by Paul Green opened on Roanoke Island. President Franklin D. Roosevelt even attended a show on Virginia Dare's 350th birthday.

The First Dare Stone: Chowan River

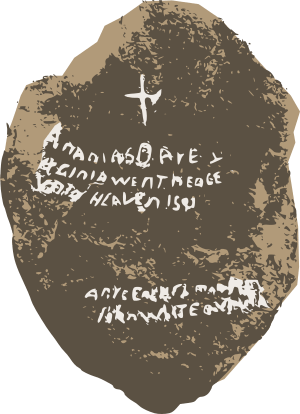

On November 8, 1937, a man named Louis E. Hammond visited Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia. He brought a 21-pound (9.5 kg) stone and asked for help understanding its carvings. Hammond said he was a tourist from California traveling with his wife. He claimed he found the stone in August 1937. It was on the east bank of the Chowan River in Chowan County, North Carolina.

One side of the stone read:

|

ANANIAS DARE & |

Ananias Dare & |

The other side had more details:

|

FATHER SOONE AFTER YOV |

Father, soon after you |

People understood the inscription as a message from Eleanor White Dare ("EWD"). It was meant to update her father, John White, about the Lost Colonists. A group of Emory professors, including Haywood Pearce, Jr., went with Hammond to the spot where he said he found the stone. They could not find the exact location. But the trip made the professors believe Hammond was telling the truth. Emory announced the discovery on November 14, 1937.

Pearce published his findings in a history journal in May 1938. He wrote that the stone's truthfulness "can never be fully and finally established." But he argued that the stone's story matched Strachey's account. This account spoke of seven survivors of a massacre who escaped up the Chowan River. Pearce also said the spelling on the stone was like Elizabethan English. He noted that the colonists likely had the tools to carve such a message.

More Stones Appear

Because Hammond's stone mentioned a rock marking a burial site, rumors spread about Virginia Dare's tombstone. Pearce felt that finding this second stone would prove the first one was real. It would also make the finder famous. Emory decided not to buy the Chowan River stone from Hammond in 1938. So, Pearce made his own offer. He had money from Brenau University, which his father owned.

Pearce, his father, and his stepmother Lucille made several trips to Edenton, North Carolina. They searched and dug in 1938 and 1939. To get the local community's attention, they spoke to groups. They also offered a reward of about $500 (in 1939 money) to anyone who could find the second stone.

Two men from North Carolina claimed to have found the stone the Pearces were looking for. But there are no records that the Pearces checked their claims. These stones were never added to the Brenau collection.

Stones from Bill Eberhardt

In May 1939, a man named Bill Eberhardt brought several stones to Brenau. He said he found them on a hill near Greenville County, South Carolina. At first, his finds were not taken seriously. But then the Pearces showed him Hammond's stone. They explained what kind of writing they hoped to find. Soon after, Eberhardt brought a stone that matched their description. The Pearces quickly tried to buy the hill. But Eberhardt claimed he had already removed all the carved stones from the site.

Eberhardt was a stonecutter from Fulton County, Georgia. He had a history of selling fake Native American artifacts. But he only had a third-grade education. So, the Pearces thought he was not smart enough to trick them. As a test, they offered him a choice. He could have the original $500 reward. Or he could have $100 cash plus half of whatever was found at the hill. Eberhardt chose the second option. This made the Pearces believe he truly thought his finds were valuable. (Later, Eberhardt secretly sold his share of the hill when his stones were getting a lot of attention.)

Thirteen stones Eberhardt supposedly found were added to Brenau's collection. These were Dare Stones Numbers 2–14. (Hammond's stone became Number 1.) The carvings on these new stones were very different from Hammond's. They had large, mixed-case letters in a loose, rounded style. They also said the 1591 massacre happened in South Carolina. This was about 400 miles (640 km) from the Chowan River. Pearce, Jr., tried to explain this. He suggested that Stone Number 1 was carved in South Carolina and then carried to North Carolina by a Native American.

Dare Stone Number 2 had the words "Father wee goe sw" (Father we go southwest). The Pearces thought this meant the colonists traveled along the Chattahoochee River into Georgia. They asked Eberhardt to look for more stones there. This idea seemed right when Dare Stone Number 15 was reported in July 1939. Isaac Turner of Atlanta claimed he found his stone in Hall County, Georgia in March. This was before the Pearces started working with Eberhardt. The Turner stone looked like Eberhardt's stones. It claimed the Lost Colonists "pvtt moche clew bye waye" (put many clues by the way) for John White to find.

In August 1939, Eberhardt brought nine more stones (Numbers 16–24) to Brenau. He said he found them in Habersham County, Georgia. The story on these stones said Eleanor and the other colonists traveled toward a "great Hontoaoase lodgement." They lived in "primaeval splendour" (ancient splendor) between 1591 and 1593.

When Eberhardt brought three new stones to Brenau in August 1940, he offered to show the Pearces where he found them. The spot was in Fulton County, Georgia, four miles from Eberhardt's home. When they arrived, Eberhardt handed over four more stones. He ignored their instructions to leave them where they were found. These seven stones became Dare Stone Numbers 25–31. Stone 26 said Eleanor became the wife of a Native American chief in 1593. Stone 28 mentioned requests in 1598 for John White to take her daughter to England. Stone 25 was Eleanor Dare's tombstone, saying she died in 1599.

Eberhardt also showed the Pearces a carving like the Dare Stones inside a cave near the Chattahoochee River. This find was not given a number until a teenager chipped off the ledge and took it. After getting the pieces back, the Pearces called them Dare Stone Number 47. The message simply said Eleanor had been living near the cave since 1593. This stone and Stone 25 suggested a six-year period in one place. This made it seem likely Eberhardt would find more stones nearby.

During September 1940, Eberhardt brought 13 more stones (Numbers 32–35 and 37–45). Again, he ignored instructions to leave them where they were. He claimed they were found near his home. Stone Number 37, found near Jett Mill outside Roswell, Georgia, was presented as a joint discovery by Eberhardt and Turner (who found Stone 15). Stone Number 36 was given to the Pearces by William Bruce of Atlanta. He claimed to have found it near the Powers Ferry Bridge over Nancy Creek, not far from his home. Five of these stones (38, 39, 40, 41, and 43) were tombstones for Lost Colonists. The Dare Stones described seven survivors and the deaths of six of them. Stones 44 and 45 were said to be from Griffen Jones (the group's stonecutter) and Agnes Dare, Eleanor's daughter.

Pearce, Jr., believed the story behind Dare Stone Number 46 proved the stones were real. Eberhardt and Turner supposedly talked to Tom Jett, whose family used to own Jett Mill. Jett claimed he found a stone like Stone 37. He and his brother split it in two. One half supposedly ended up in his father-in-law's tool chest 15 years earlier. Jett's nephew remembered seeing the other half and quickly found it in a ditch. The two pieces fit together perfectly. This was enough for Pearce to believe the stories of so many people.

The last stone in the Brenau collection was brought by Eberhardt in December 1940. Dare Stone Number 48, supposedly found near the cave, read: "John White manye prisoner fourtie mylles nw. Griffen Jones & Agnes Dare 1603." The meaning of this new part of the story was not explored before the hoax was revealed.

Experts Look at the Stones

The Pearces planned to have a meeting of experts at Brenau in September 1939. Scholars could examine the Dare Stones and decide if they were real. But days before the meeting, the Pearces postponed it until the next autumn. They said they needed more time to review new evidence. This likely referred to the stones that suggested the Lost Colonists reached Georgia.

The meeting was held on October 19–20, 1940. Thirty-four experts attended. These included archaeologists, historians, geologists, and language experts. The presence of Samuel Eliot Morison, a history professor from Harvard University, made the meeting seem very important. The guests looked at the stones and learned how they were found. Tom Jett came to the meeting to say he had seen Dare Stone Number 46 when he was a child.

The experts chose a five-person committee, led by Morison. They released a first report to the news. This statement supported the idea that the Dare Stones were real. But it also warned that the investigation was still going on. Despite this caution, news reports mostly said the Dare Stones had been proven true.

Morison later said he did not fully support the stones. In 1971, he wrote that his committee "politely as possible, declared the stones to be fake." He said this was mainly because two words, "trail" and "reconnoitre," were not used in English until a century or more after 1590.

Proof of a Hoax

Newspaper Investigation

In December 1940, Haywood Pearce, Jr., sent an article about the Dare Stones to The Saturday Evening Post magazine. The magazine's editors were doubtful. But they accepted the article. However, their fact-checking team struggled with a discovery that went against known history. The magazine asked a reporter, Boyden Sparkes, to investigate Pearce's story. They wanted to know if it was worth publishing.

Instead of Pearce's article, the Post published Sparkes's article on April 26, 1941. It challenged whether the Dare Stones were real. Sparkes found that no one could find Louis E. Hammond after he left Emory. No one had met the wife he claimed to be traveling with in 1937. No one saw the car he said he used to carry the stone. Hammond claimed he cleaned Dare Stone Number 1 with a wire brush. This removed an important way to check if the stone was real.

Sparkes easily found that Bill Eberhardt, Isaac Turner, and William Bruce had known each other for years. Turner had also been a childhood friend of Tom Jett. He noticed it was suspicious that Eberhardt found most of the Dare Stones. He was always alone or with his friend Turner. And the stones were always found along a path leading toward Eberhardt's own home. Sparkes believed the stones were fakes. But he did not say the Pearces were involved in the trick. However, he criticized Pearce, Jr., for promoting evidence that favored the stones, while downplaying evidence against them.

A 1991 book tried to say that all 48 of Brenau's Dare Stones were real. But this idea did not get much support. Most people still believed Eberhardt's stones were fake.

Blackmail Attempt

After the Post article, Eberhardt tried to sell Pearce, Jr., another stone. But Pearce had become suspicious. Eberhardt tried again. This time, he finally led Pearce to a carving on a cliff near the cave where Stone 47 was found. Pearce returned later with a geologist, Count Gibson. Gibson found a bottle of sulfuric acid. He thought it had been used to make the carving look old. Pearce told Eberhardt he would not buy any more stones from him. Neither of these new carvings were added to the Brenau collection.

Eberhardt later met with Pearce's mother, Lucille, about a new artifact. When they met, he showed her a stone like his earlier finds. It was carved with "Peace and Dare Historical Hoaxes. We Dare Anything." Mrs. Pearce said Eberhardt demanded $200 from the Pearces. If they did not pay, he would send the stone to The Saturday Evening Post. He would also confess to faking all the Dare Stones he had produced.

On May 13, 1941, there was a tense meeting. Eberhardt kept his distance, holding a rifle. Pearce, Jr., with Gibson as a witness, tried to get Eberhardt to sign a contract that would be a confession. The Pearce family told their side of the story to the newspapers. They admitted that most of the Dare Stones were hoaxes. Eberhardt denied trying to get money from them. But he did claim he found the "We Dare Anything" stone just like the others. News reports generally said all the Dare Stones were hoaxes. They did not always say which ones were linked to Eberhardt.

What About the First Stone Today?

Even though the Dare Stones linked to Bill Eberhardt were shown to be fake, the first stone could not be connected to him. Boyden Sparkes kept trying to investigate Louis E. Hammond. He hoped to find a link to Eberhardt or other proof that the first Dare Stone was also fake. But he had little success.

A 1983 study by an archaeologist named Robert L. Stephenson did not give a clear answer. Stephenson easily said three of the Eberhardt stones were fakes. But he could not find any way to test the Hammond stone that would show if it was real or fake.

In 2016, a piece of the Chowan River Stone was cut from the bottom for testing. This test showed that the rock was not a ballast stone from an English ship. (Ballast stones are heavy rocks used to balance a ship.) It also showed that the inside of the stone was bright white. The outside was weathered gray. This sharp contrast would make the stone good for carving messages. It would take a long time for the bright letters to fade. Using chemicals to make such a carving look old would need a lot of skill, especially in the 1930s.

Matthew Champion, an expert on old carvings, said the Chowan stone looks like carvings he studies in English churches. He said that using Roman letters or modern numbers was not unusual for that time. Kevin Quarmby, a professor who studies Shakespeare, said the language on the Chowan Stone matched English from the Elizabethan era. Quarmby noticed "subtle nuances" (small details) in the message. This suggested it was either real or a very clever fake. However, Quarmby admits he is not an expert on old handwriting. In contrast, a historian named Diarmaid MacCulloch said the language on the stone was a "ridiculous forgery." He said it was as believable as Dick Van Dyke's fake accent in the movie Mary Poppins.

Champion believes that the stone's truthfulness cannot be decided without a serious archaeological project. This would involve many different types of experts. However, experts are careful about risking their professional reputations on the Dare Stones. This makes such a project hard to organize.

In 2019, a theory suggested the Chowan River Stone was a fake linked to another hoax, the Plate of Brass hoax. This theory said L.E. Hammond was not a real tourist. It claimed he was a professor from New Mexico who worked with Haywood Pearce, Jr., and Herbert E. Bolton, who was behind the Plate of Brass hoax. But in 2021, this theory was discussed and dismissed.

The Stones Today

After the scandal in 1941, Brenau University removed the 47 fake Dare Stones from public display. The original stone was displayed in the Brenau library. After a TV show in 2015 brought more attention to it, the school's president moved the stone to his office. He said this was for security reasons. The other stones were put in different places over time. They ended up under the school's auditorium, in a boiler room, and finally in the attic of one of the campus houses.

Brenau has allowed all the stones to be examined for different investigations. They worked with TV documentaries in 1979, 2015, and 2017. The school's website has an official policy for people who want to see and examine the stones. But the school keeps all rights to photograph and video record the stones.

|