Demographic history of Scotland facts for kids

The history of Scotland's population tells us how the number of people living in what is now Scotland has changed over thousands of years. The first people might have arrived during a warm period in the last Ice age (around 130,000–70,000 BC). But the oldest proof we have of people living there comes from Mesolithic hunter-gatherers. These early people moved around a lot, often using boats, and there weren't many of them.

Around 3500 BC, Neolithic farming began. This led to people settling down in one place, and the population started to grow. Evidence like hillforts shows that more people were living in settled communities. Later, when the Romans invaded in the first century AD, the native population was negatively affected.

We don't have many written records about how many people lived in Scotland during the early Middle Ages. Back then, many babies were born, but many people also died young. The population might have grown from half a million to one million by the mid-1300s. But then the terrible Black Death arrived. This disease might have cut the population down to as low as half a million by the late 1400s. About half the people lived north of the River Tay. Around 10% lived in the burghs (towns) that grew during this time.

Prices going up (which means more demand for food) suggests the population kept growing until the late 1500s. It then stayed about the same for a while. In the late 1600s, things became more stable, and the population started to grow again. The first good records from 1681 show about 1.2 million people. This number likely dropped because of the "seven ill years" in the 1690s. This was a time of severe hunger and many people died, especially in the north.

The first national count of people (census) was in 1755. It showed Scotland had 1,265,380 people. By then, four towns had more than 10,000 residents. Edinburgh, the capital, was the largest with 57,000 people.

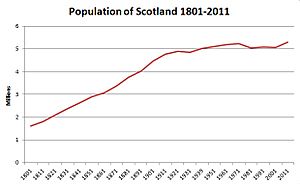

Scotland's population grew very quickly in the late 1700s and 1800s. The Lowland Clearances caused people to move away from some areas. In the Highland Clearances, some areas in the Highlands also lost people, but the overall population there kept growing for a while. By 1801, Scotland had 1,608,420 people. This grew to 2,889,000 in 1851 and 4,472,000 in 1901.

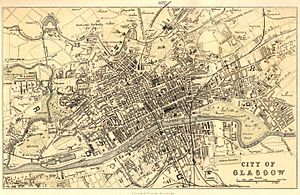

By the early 1900s, one out of every three Scots lived in the four big cities: Glasgow, Edinburgh, Dundee, and Aberdeen. Glasgow became the biggest city, with 762,000 people by 1901. It was even called "the Second City of the Empire" (after London). Even though industries grew, there weren't enough jobs for everyone. So, between the mid-1800s and the Great Depression, about two million Scots moved to North America and Australia. Another 750,000 moved to England.

Scots made up only 10% of the British population. But they provided 15% of the soldiers in the national army. Sadly, they accounted for 20% of the deaths in World War I (1914–18). After mass migration ended, the population reached its highest point of 5,240,800 in 1974. After that, it slowly dropped to 5,062,940 in 2000. Some city populations also fell because of plans to clear old, poor housing and move people to new towns. For example, Glasgow's population dropped from over a million in 1951 to 629,000 in 2001. Rural areas, especially the Highlands and Hebrides, also saw fewer people.

Early People and Roman Times

During a warm period in the last Ice age (about 130,000–70,000 BC), the climate in Europe was warmer than it is today. Early humans might have travelled to what is now Scotland, but we haven't found any proof of this. Later, huge glaciers covered most of Britain. Scotland only became a place where people could live again around 9600 BC, after the ice melted.

The first known settlements were Mesolithic hunter-gatherer camps. Archaeologists found a site near Biggar that dates back to about 8500 BC. Many other sites across Scotland show us that these people moved around a lot. They used boats and made tools from bone, stone, and antlers. There were probably very few people living in Scotland at this time.

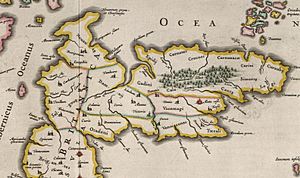

Neolithic farming brought permanent settlements. For example, the stone house at Knap of Howar on Papa Westray was built around 3500 BC. These settlements meant more people could live closer together. The Roman geographer Ptolemy wrote about 19 "towns" in Caledonia (north of Roman Britain). But we haven't found clear proof of cities. These "towns" were probably hillforts. Over 1,000 such forts have been found, mostly south of the Clyde-Forth line. Most of them seem to have been left empty during the Roman period.

We also find unique stone wheelhouses (round houses with stone pillars like wheel spokes) and over 400 small underground souterrains (tunnels possibly used for storing food). Studies of Black Loch in Fife show that farmland grew, and forests shrank, from about 2000 BC until the Romans came in the first century AD. This suggests the settled population was growing. After the Roman invasions, birch, oak, and hazel trees grew back for about 500 years. This suggests the Roman presence had a negative effect on the local population.

The Middle Ages

We have almost no written records to figure out how many people lived in Scotland during the early Middle Ages. Experts guess that Dál Riata had about 10,000 people, and Pictland (the largest region) had 80,000–100,000. In the 400s and 500s, more people probably died because of the bubonic plague. This might have reduced the population. Looking at burial sites from this time, like Hallowhill in St Andrews, shows that people only lived to be about 26 to 29 years old.

Life back then was likely a "high fertility, high mortality" society. This means many babies were born, but many people also died young. It was similar to developing countries today. The population was quite young, and women probably had many children (though many children died young). This meant there weren't many workers for each person who needed to be fed. It was hard to produce extra food, which made it difficult for the population to grow much or for societies to become more complex.

From the time the Kingdom of Alba was formed in the 900s, until the Black Death arrived in 1349, the population may have grown from half a million to one million. This is based on how much land could be farmed. This growth was probably interrupted by occasional problems, like the famines recorded in 1154 and 1256. More serious were several bad harvests in the early 1300s across Europe, causing widespread hunger in 1315–16 and the late 1330s.

We don't have exact numbers for how many people died from the Black Death in Scotland. But there are some clues. Walter Bower wrote that 24 (about a third) of the priests at St. Andrews died during the outbreak. There are also stories about empty farmlands in the years that followed. If Scotland was like England, the population might have dropped to as low as half a million by the end of the 1400s. Compared to later times, the population was spread out more evenly across the kingdom. About half the people lived north of the River Tay.

Early Modern Times

Prices for food went up, which usually means more people needed food. This suggests the population was still growing in the first half of the 1500s. Almost half the years in the late 1500s saw food shortages, either locally or across the country. This meant large amounts of grain had to be brought in from other places. Problems got worse with outbreaks of plague, especially in 1584-8, 1595, and 1597–1609. The population growth probably stopped after the hunger of the 1590s, as prices were quite steady in the early 1600s.

Hunger was common, with four periods of very high food prices between 1620 and 1625. The wars of the 1640s greatly affected Scotland's economy. Crops were destroyed, and markets were disrupted, causing some of the fastest price increases of the century. But the population probably grew in the Lowlands after the Restoration in 1660, when things became more stable. There's also evidence that the Highlands had a different pattern, with growth likely continuing from the early 1600s to the late 1700s.

Records from 1691 suggest a population of about 1.2 million. The population might have been seriously affected by the bad harvests (1695, 1696, and 1698-9) known as the "seven ill years". This led to severe hunger and fewer people, especially in the north. Starvation probably killed 5% to 15% of Scotland's population. In some areas, like Aberdeenshire, death rates reached 25%. The famines of the 1690s were seen as very bad. This was partly because hunger had become quite rare in the late 1600s, with only one year of scarcity (in 1674). The shortages of the 1690s were the last of their kind.

Between 1650 and 1700, about 7,000 Scots moved to America. Another 10,000–20,000 went to Europe and England, and 60,000–100,000 went to Ireland. The first reliable number for the national population comes from a census in 1755. It showed Scotland had 1,265,380 people.

Unlike in England, where villages with many houses existed early on, most people in Scotland lived in small groups of houses called clachans or townships. These were often groups of houses shared by four to six tenants who farmed together. As the population grew, some of these settlements split to form new ones. People also started living on less fertile land. sheilings (small groups of huts used for summer grazing) became permanent homes.

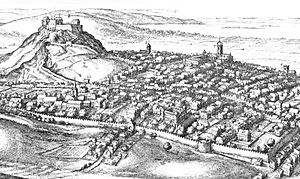

About 10% of the population lived in the burghs (towns) that had grown since the Middle Ages. Most of these were in the east and south of the country. They probably had an average of 2,000 people. But many were much smaller than 1,000. The largest, Edinburgh, likely had over 10,000 people at the start of this period. Edinburgh doubled in size in the century after 1540, especially after the plague of 1580. Most of its new residents probably came from the growing countryside nearby. It also expanded outside its city walls into areas like Cowgate, Bristo, and Westport. By 1750, including its suburbs, Edinburgh had 57,000 people.

By the end of this period, the only other towns with over 10,000 people were Glasgow (32,000), Aberdeen (around 16,000), and Dundee (12,000). By 1600, Scotland had a higher percentage of its people living in larger towns than places like Scandinavia, Switzerland, and most of Eastern Europe. By 1750, in Europe, only Italy, the Low Countries, and England had more people living in cities than Scotland.

Modern Times

The Scottish Agricultural Revolution changed how farming was done in Lowland Scotland. Thousands of cottars (small farmers) and tenant farmers moved from farms to the new industrial cities like Glasgow, Edinburgh, and northern England. After the end of the boom caused by the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (1790–1815), Highland landlords needed money. They used to get rent in goods, but now they wanted money.

They forced out farmers who lived on run rig (shared farmland) and shared grazing areas. Their lands were then rented to large sheep farmers who could pay much higher rents. Forcing tenants out went against dùthchas, which was the idea that clan members had a right to rent land in their clan's area. Especially in the north and west Highlands, landowners offered new homes in crofting communities. They wanted the moved tenants to work in fishing or the kelp industry (making products from seaweed). These forced moves were the first part of the Highland Clearances.

The total population of the Highlands kept rising throughout the clearances. But there was a constant movement of people away from the land. They went to cities, and further away to England, Canada, America, and Australia. The Great Famine of Ireland in the 1840s, caused by potato disease, reached the Highlands in 1846. The crowded crofting communities relied heavily on potatoes. About 150,000 people faced disaster. But they were saved by a good emergency relief system. This was very different from the failed relief efforts in Ireland and prevented a major population crisis in Scotland.

By the first national census in 1801, Scotland's population was 1,608,420. It grew steadily in the 1800s, reaching 2,889,000 in 1851 and 4,472,000 in 1901. While some rural areas lost people, towns grew quickly. Aberdeen, Dundee, and Glasgow grew by a third or more between 1755 and 1775. The textile town of Paisley more than doubled its population. Because of the Industrial Revolution, Scotland was already one of the most urbanized (city-living) societies in Europe by 1800.

In 1800, 17% of people in Scotland lived in towns with more than 10,000 residents. By 1850, it was 32%, and by 1900, it was 50%. By 1900, one out of every three people lived in the four big cities: Glasgow, Edinburgh, Dundee, and Aberdeen. Glasgow became the largest city. Its population was 43,000 in 1780, growing to 147,000 by 1820. By 1901, it had grown to 762,000. This was due to many births and people moving in from the countryside and especially from Ireland. But from the 1870s, the birth rate fell, and fewer people moved in. Much of the growth was then due to people living longer. Glasgow was one of the largest cities in the world and was known as "the Second City of the Empire" after London.

Death rates were high compared to England and other European countries. Records suggest that 30 out of every 1,000 people died in 1755. This dropped to 24 in the 1790s and 22 in the early 1860s. Death rates were usually much higher in cities than in the countryside. When first measured (1861–82), the death rate in the four major cities was 28.1 per 1,000, while in rural areas it was 17.9. Death rates probably peaked in Glasgow in the 1840s. This was when many people moved into the city from the Highlands and Ireland. The population grew faster than the city's sanitation could handle, leading to outbreaks of diseases.

National death rates began to fall in the 1870s, especially in cities, as living conditions improved. By 1930–32, the national rate was 13.4 per 1,000. In cities, it was 14.1, and in rural areas, it was 12.8.

Even with growing industries, there weren't enough good jobs. So, from 1841 to 1931, about two million Scots moved to North America and Australia. Another 750,000 Scots moved to England. With a population of 4.8 million in 1911, Scotland sent 690,000 men to the First World War. Of these, 74,000 died in battle or from disease, and 150,000 were seriously wounded. So, even though Scots were only 10% of the British population, they made up 15% of the national armed forces. They also accounted for 8.3% of the UK's total 887,858 deaths from all causes.

While people stopped moving away from England and Wales after World War I, it continued in Scotland. An estimated 400,000 Scots (10% of the population) left the country between 1921 and 1931. When the Great Depression hit in the 1930s, there were no easy jobs in the US and Canada. Emigration fell to less than 50,000 a year. This ended the period of large-scale migrations that had started in the mid-1700s.

This contributed to the population growth, which reached its highest point of 5,240,800 in 1974. After that, it slowly dropped to 5,062,940 in 2000. Some city populations also decreased because of slum clearance (getting rid of old, poor housing) and moving people to new towns. For example, Glasgow's population fell from over a million in 1951 to 629,000 in 2001. Rural areas also lost people, especially the Highlands and Hebrides. In the early 2000s, Scotland's population rose again to 5,313,600 (its highest ever recorded) at the 2011 census.

See also

- Demographic history, how populations change around the world

- Demography of Scotland, current population facts about Scotland