Scotland in the Middle Ages facts for kids

Scotland in the Middle Ages is about the history of Scotland from when the Romans left until the early 1500s. This was a time when new ideas from the Renaissance started to arrive.

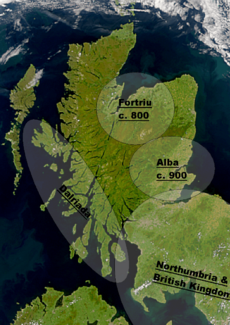

From the 400s, northern Britain had many small kingdoms. The most important were the Picts, the Gaels of Dál Riata, the Britons of Strathclyde, and the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Bernicia (later Northumbria). In the late 700s, Vikings arrived. They set up their own rulers and settlements along the coasts and islands.

In the 800s, the Scots and Picts joined together. They formed a single kingdom called Alba. It had a Pictish base but was mostly influenced by Gaelic culture. After King David I ruled in the 1100s, Scottish kings became more like the French. They preferred French culture over native Scottish ways. Alexander II and his son Alexander III took back the western coast. This led to the Treaty of Perth with Norway in 1266.

Scotland was invaded and taken over for a short time. But it regained its freedom from England. Important figures like William Wallace in the late 1200s and Robert Bruce in the 1300s helped achieve this.

In the 1400s, under the Stewart Dynasty, Scotland had a lot of political changes. But the king gained more power over independent lords. Most lost land was taken back, making Scotland's borders similar to today's. However, the Auld Alliance with France led to a big defeat for the Scottish army. This happened at the Battle of Flodden in 1513. King James IV died there. This was followed by a long time when the king was too young to rule, causing political trouble. Kingship was the main way of governing. It became more advanced in the late Middle Ages. Wars also changed. Armies became larger, navies grew, and new weapons like cannons and stronger forts were developed.

The Church in Scotland always followed the Pope. It brought in monasticism (monk life). From the 1000s, it adopted church reforms. This led to a strong religious culture that stayed independent from English control.

Scotland grew from its base in the eastern Lowlands. It expanded to roughly its modern borders. The varied landscapes protected it from invasions. But they also made it hard for the central government to control everything. The land also shaped the economy, which was mostly about raising animals. The first towns, called burghs, were created from the 1100s. The population might have reached one million before the Black Death arrived in 1350. In the early Middle Ages, society had a small group of nobles and many free people and slaves. Serfdom (being tied to the land) disappeared in the 1300s. New social groups also started to grow.

The Pictish and Cumbric languages were replaced by Gaelic, Scots, and later Norse. Gaelic became the main cultural language. From the 1000s, French was used at court. In the late Middle Ages, Scots, which came from Old English, became dominant. Gaelic was mostly spoken in the Highlands. Christianity brought Latin, written culture, and monasteries as learning centers. From the 1100s, chances for education grew. This led to more education for ordinary people, ending with the Education Act 1496. Until the 1400s, when Scotland got three universities, Scots who wanted higher education had to go to England or Europe. Some became famous internationally. Writings from the early Middle Ages survive in all the main languages. Scots became an important literary language from John Barbour's Brus (1375). This led to a culture of poetry by court poets called makars, and later, important prose works. Art from the early Middle Ages survives in carvings, metalwork, and beautiful illuminated books. These helped develop the wider insular style. Much of the best later art is lost. But a few key examples remain, especially works ordered from the Netherlands. Scotland had a strong musical tradition. Secular music was made and performed by bards. From the 1200s, church music was more and more influenced by European and English styles.

Contents

- Scotland's Political Journey

- How Scotland Was Governed

- Warfare in Medieval Scotland

- Religion in Medieval Scotland

- Scotland's Geography and Borders

- Economy and Society in Medieval Scotland

- Culture in Medieval Scotland

- Scottish Identity

Scotland's Political Journey

Early Kingdoms and Changes

Small Kingdoms Emerge

After the Romans left Britain, four main groups became powerful in what is now Scotland. In the east were the Picts. Their kingdoms eventually stretched from the River Forth to Shetland. The first strong Pictish king was Bridei mac Maelchon (ruled around 550–584). His power was based at the fort of Craig Phadrig near Inverness. After him, leadership moved to the Fortriu people. They lived around Strathearn and Menteith. Christian missionaries from Iona started converting the Picts to Christianity around 563.

In the west lived the Gaelic-speaking people of Dál Riata. Their main fort was Dunadd in Argyll. They had strong ties with Ireland, where they got the name "Scots." In 563, St. Columba came from Ireland. He founded the monastery of Iona off Scotland's west coast. He likely started converting this area to Christianity. The kingdom was strongest under Áedán mac Gabráin (ruled 574–608). But his expansion was stopped at the Battle of Degsastan in 603 by Æthelfrith of Northumbria.

In the south was the British Kingdom of Strathclyde. These people were descendants of Roman-influenced kingdoms. Their capital was at Dumbarton Rock. In 642, they defeated Dál Riata. But the kingdom was attacked by the Picts and Northumbrians between 744 and 756. After this, little is known until Dumbarton was burned in 780.

Finally, there were the "Angles," Germanic invaders. They had taken over much of southern Britain. They held the Kingdom of Bernicia in the south-east. The first Angle king was Ida, around 547. Ida's grandson, Æthelfrith, joined his kingdom with Deira to form Northumbria around 604. The kingdom was later reunited under Oswald (ruled 634–642). He had become Christian while in exile in Dál Riata. He looked to Iona for missionaries to help convert his kingdom.

How the Kingdom of Alba Began

Things changed in 793 AD when fierce Vikings started raiding monasteries like Iona. This caused fear across northern Britain. Orkney, Shetland, and the Western Isles eventually fell to the Norsemen. In 839, the kings of Fortriu and Dál Riata died in a big defeat by the Vikings. A mix of Viking and Irish settlers in south-west Scotland created the Gall-Gaidel, or Norse Irish. This is where the region of Galloway gets its name. Around the 800s, the Kingdom of Dál Riata lost the Hebrides to the Vikings.

These threats might have sped up a process where Pictish kingdoms became more Gaelic. They adopted Gaelic language and customs. The Gaelic and Pictish crowns also merged. Historians still discuss if it was a Pictish takeover of Dál Riata, or the other way around. This led to the rise of Cínaed mac Ailpín (Kenneth MacAlpin) in the 840s. He brought the House of Alpin to power. In 867 AD, the Vikings took Northumbria, forming the Kingdom of York. Three years later, they attacked the Britons' fort of Dumbarton. They later conquered much of England, except for a smaller Kingdom of Wessex. This left the new combined Pictish and Gaelic kingdom almost surrounded. When he died as king of the combined kingdom in 900, Domnall II (Donald II) was the first to be called rí Alban (King of Alba). The name Scotia was increasingly used for the kingdom north of the Forth and Clyde. Eventually, the whole area controlled by its kings was called Scotland.

High Middle Ages: Growth and Change

Gaelic Kings: From Constantine II to Alexander I

The long rule (900–942/3) of Causantín (Constantine II) is key to how the Kingdom of Alba formed. He was later known for making Scottish Christianity follow the Catholic Church. After many battles, his defeat at Brunanburh led him to retire as a monk at St. Andrews. The time between Máel Coluim I (Malcolm I) and Máel Coluim mac Cináeda (Malcolm II) was peaceful with England. But it had many internal family disagreements. In 945, Máel Coluim I took over Strathclyde. This was part of a deal with King Edmund of England. However, they lost control in Moray. King Donnchad I (Duncan I) ruled from 1034. His reign was troubled by failed military plans. He was defeated and killed by Macbeth, who became king in 1040. Macbeth ruled for 17 years. He was then overthrown by Máel Coluim, Duncan's son. Máel Coluim later defeated Macbeth's step-son, Lulach, to become King Máel Coluim III (Malcolm III).

It was Máel Coluim III who got the nickname "Canmore" ("Great Chief"). He passed this name to his family. He did the most to create the Dunkeld dynasty. This family ruled Scotland for the next two centuries. His second marriage to the Anglo-Hungarian princess Margaret was very important. This marriage, and raids on northern England, made William the Conqueror invade. Máel Coluim accepted his authority. This opened Scotland to later claims of power by English kings. When Malcolm died in 1093, his brother Domnall III (Donald III) became king. However, William II of England supported Máel Coluim's son, Donnchad. He seized power. His murder within months brought Domnall back. One of Máel Coluim's sons, Edmund, became his heir. They ruled Scotland until two of Edmund's younger brothers returned from England. They also had English military support. The oldest, Edgar, became king in 1097. Soon after, Edgar and King Magnus Bare Legs of Norway made a treaty. It recognized Norwegian power over the Western Isles. In reality, Norse control of the Isles was loose. Local chiefs had a lot of freedom. Edgar was followed by his brother Alexander, who ruled from 1107–1124.

Scoto-Norman Kings: From David I to Alexander III

When Alexander died in 1124, the crown went to Margaret's fourth son, David I. He had lived most of his life as an English baron. His reign saw a "Davidian Revolution." Old Scottish ways and people were replaced by English and French ones. This helped shape later Medieval Scotland. English and Norman nobles joined the Scottish aristocracy. David introduced a system of feudal land ownership. This brought knight service, castles, and heavily armed cavalry. He created an Anglo-Norman style court. He also introduced the office of justicar to oversee justice. Local sheriffs were brought in to manage areas. He set up the first royal burghs (towns) in Scotland. He gave special rights to these settlements. This led to the first real Scottish towns and helped the economy grow. He also introduced the first recorded Scottish coins. He continued a process started by his mother and brothers. This involved setting up new monasteries based on the reforms at Cluny. He also helped organize church areas (dioceses) more like those in the rest of Western Europe.

These changes continued under his grandsons, Malcolm IV of Scotland and William I. The crown now passed down through the main family line. This led to the first of several times when the king was too young to rule. William's son Alexander II and his son Alexander III benefited from this stronger authority. They aimed for peace with England. This allowed them to expand their power in the Highlands and Islands. By Alexander III's reign, the Scots could take over the rest of the western coast. They did this after Haakon Haakonarson's failed invasion and the undecided Battle of Largs. This led to the Treaty of Perth in 1266.

Late Middle Ages: Wars and New Dynasties

Wars of Independence: From Margaret to David II

King Alexander III died in 1286. Then his granddaughter and heir, Margaret, Maid of Norway, died in 1290. This left 14 people claiming the throne. To avoid civil war, Scottish nobles asked Edward I of England to decide. Edward demanded that Scotland recognize him as its feudal lord. He then chose John Balliol, who had the strongest claim, to be king in 1292. Robert Bruce, 5th Lord of Annandale, the next strongest claimant, reluctantly accepted this. Over the next few years, Edward I used these agreements to weaken King John's power and Scotland's independence. In 1295, John, urged by his advisors, made an alliance with France. This was known as the Auld Alliance. In 1296, Edward invaded Scotland and removed King John from power. The next year, William Wallace and Andrew de Moray gathered forces to fight the English. Under their joint leadership, an English army was defeated at the Battle of Stirling Bridge. For a short time, Wallace ruled Scotland as guardian for John Balliol. Edward came north himself and defeated Wallace at the Battle of Falkirk. English nobles rejected the Pope's claim that Scotland belonged to him. They said English kings had long owned it. Wallace escaped but likely resigned as Guardian of Scotland. In 1305, he was captured by the English. They executed him for treason, even though he felt he owed no loyalty to England.

John Comyn and Robert the Bruce, grandson of the earlier claimant, were made joint guardians. On February 10, 1306, Bruce was involved in Comyn's murder in Dumfries. Less than seven weeks later, on March 25, Bruce was crowned king. However, Edward's forces took over the country after defeating Bruce's small army at the Battle of Methven. Despite Bruce and his followers being excommunicated by Pope Clement V, his support slowly grew. By 1314, with help from nobles like Sir James Douglas and Thomas Randolph, only Bothwell and Stirling castles remained under English control. Edward I had died in 1307. His heir, Edward II, moved an army north to break the siege of Stirling Castle and regain control. Robert defeated that army at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314. This secured Scotland's independence. In 1320, the Declaration of Arbroath, a letter to the Pope from Scottish nobles, helped convince Pope John XXII to reverse the excommunication. It also cancelled past acts where Scottish kings had submitted to English ones. This allowed Scotland's independence to be recognized by major European royal families. The declaration is also seen as a very important document in the growth of Scottish national identity.

In 1328, Edward III signed the Treaty of Northampton. This recognized Scottish independence under Robert the Bruce. However, four years after Robert's death in 1329, England invaded again. They claimed to be restoring Edward Balliol, John Balliol's son, to the Scottish throne. This started the Second War of Independence. Despite victories at Dupplin Moor and Halidon Hill, Edward Balliol failed to stay on the throne. This was due to strong Scottish resistance led by Sir Andrew Murray, son of Wallace's friend. Edward III lost interest in Balliol after the Hundred Years' War with France began. In 1341, David II, King Robert's son, returned from France. Balliol finally gave up his claim to the throne to Edward in 1356. He then retired to Yorkshire, where he died in 1364.

The Stewart Kings: From Robert II to James IV

After David II died, Robert II, the first of the Stewart kings, took the throne in 1371. His sick son, John, followed him in 1390. John took the name Robert III. During Robert III's reign (1390–1406), real power was mostly held by his brother, Robert Stewart, Duke of Albany. After his older son, David, Duke of Rothesay, died suspiciously in 1402, Robert feared for his younger son's safety. This was the future James I. He sent him to France in 1406. However, the English captured him on the way. He spent the next 18 years as a prisoner held for ransom. As a result, after Robert III's death, regents ruled Scotland. First, the Duke of Albany, and later his son Murdoch.

When Scotland finally paid the ransom in 1424, James, aged 32, returned with his English bride. He was determined to show his power. Several members of the Albany family were executed. He succeeded in making the crown more powerful. But this made him increasingly unpopular. He was killed in 1437. His son James II became king in 1449. He continued his father's policy of weakening powerful noble families. He notably challenged the strong Black Douglas family. His attempt to take Roxburgh from the English in 1460 succeeded. But it cost him his life, as he was killed by an exploding cannon.

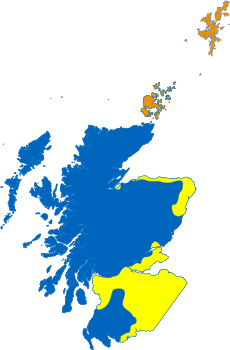

His young son became King James III. This led to another period of regents. Robert, Lord Boyd became the most important figure. In 1468, James married Margaret of Denmark. He received the Orkney and Shetland Islands as part of her dowry. In 1469, the King took control. He executed members of the Boyd family and his brothers, Alexander, Duke of Albany and John, Earl of Mar. This led to Albany leading an English-backed invasion and becoming the effective ruler. The English retreated, taking Berwick for the last time in 1482. James was able to regain power. However, the King upset the nobles, his former supporters, his wife, and his son James. He was defeated at the Battle of Sauchieburn and killed in 1488.

His successor James IV successfully ended the almost independent rule of the Lord of the Isles. He brought the Western Isles under royal control for the first time. In 1503, he married Margaret Tudor, daughter of Henry VII of England. This laid the groundwork for the Union of the Crowns in the 1600s. However, in 1512, the Auld Alliance was renewed. Under its terms, when the French were attacked by the English under Henry VIII the next year, James IV invaded England to help. The invasion was decisively stopped at the Battle of Flodden. The King, many nobles, and a large number of soldiers were killed. Once again, Scotland's government was run by regents for the infant James V.

How Scotland Was Governed

In the Early Middle Ages, kingship was the main way to organize power. There were many small kingdoms competing. Kings were mainly war leaders. But there were also special ceremonies, like coronations. When the Scots and Picts united from the 900s, forming the Kingdom of Alba, some of these ceremonies continued. Coronations still happened at Scone. While Scottish kings often moved around, Scone remained very important. Royal castles at Stirling and Perth became key in the later Middle Ages. Then Edinburgh became the capital in the late 1400s. The Scottish crown gained more respect over time. It adopted the usual roles of European royal courts. Later, it added elements of their ceremonies and grandeur.

In the early period, Scottish kings relied on powerful lords called mormaers (later earls) and Toísechs (later thanes). But from King David I's reign, sheriffdoms were introduced. This allowed more direct control and slowly limited the power of major lords. We don't know much about early law systems. But justice developed from the 1100s onwards. Local sheriff, burgh, manorial, and church courts appeared. The office of the justicar oversaw administration. Scottish common law began to grow during this time. There were efforts to organize and write down laws. Educated lawyers also started to emerge. In the Late Middle Ages, important government bodies developed. These included the privy council and parliament. The council became a full-time body in the 1400s. It was increasingly run by ordinary people and was vital for justice. Parliament also became a major legal body. It gained control over taxes and policies. By the end of this era, it met almost every year. This was partly because kings were often too young to rule. This might have stopped Parliament from being pushed aside by the monarchy.

Warfare in Medieval Scotland

In the Early Middle Ages, land warfare involved small groups of household troops. They often carried out raids and small-scale fights. The arrival of the Vikings brought a new level of naval warfare. They used fast longships. The birlinn, which came from the longship, became very important for fighting in the Highlands and Islands. By the High Middle Ages, the kings of Scotland could command armies of tens of thousands of men for short times. This "common army" was mostly made up of lightly armored spearmen and archers. After feudalism came to Scotland, these forces were joined by small numbers of mounted, heavily armored knights. Feudalism also brought castles to the country. At first, these were simple wooden motte-and-bailey castles. But in the 1200s, they were replaced by stronger stone "enceinte" castles with high encircling walls. In the 1200s, the threat from Scandinavian navies lessened. The kings of Scotland could then use naval forces to help control the Highlands and Islands.

Scottish armies rarely matched the usually larger and more professional English armies. But they were used very well by Robert I at Bannockburn in 1314 to secure Scottish independence. He also used naval power to support his forces. He began to develop a royal Scottish navy. Under the Stewart kings, these forces were further strengthened by special troops. These included men-at-arms and archers, hired through agreements called manrent. New "livery and maintenance" castles were built to house these troops. Castles also started to be changed to use gunpowder weapons. This meant adding "keyhole" gun ports, platforms for guns, and stronger walls to resist bombardments. Ravenscraig, started around 1460, is probably the first castle in Britain built as an artillery fort. It had "D-shape" bastions that could better resist cannon fire and mount artillery. Most late medieval forts built by nobles in Scotland were tower houses. These were mainly for protection against small raiding parties, not major sieges. Extensive building and rebuilding of royal palaces in the Renaissance style likely began under James III. It sped up under James IV. However, in the early 1500s, one of the best-armed and largest Scottish armies ever gathered was still defeated by an English army at the Battle of Flodden in 1513. This battle saw many ordinary soldiers, a large part of the nobility, and King James IV himself killed.

Religion in Medieval Scotland

Christianity probably came to what is now lowland Scotland from Roman soldiers. It likely survived among the British people in southern Scotland. But it faded as pagan Anglo-Saxons moved in. Scotland was mostly converted by Irish-Scots missions. These were linked to figures like St Columba from the 400s to the 600s. These missions often set up monasteries and churches that served large areas. Because of this, some scholars believe there was a special kind of Celtic Christianity. In this, abbots were more important than bishops. Rules about priests marrying were more relaxed. There were also some differences in practices with Roman Christianity. This included the way hair was cut (tonsure) and how Easter was calculated. Most of these issues were settled by the mid-600s. After Scandinavian Scotland became Christian again from the 900s, Christianity under the Pope was the main religion.

During the Norman period, the Scottish church went through many changes. With support from the king and nobles, a clearer church structure with local churches developed. Many new monasteries, following European reforms, became common. The Scottish church became independent from England. It developed a clearer system of church areas (dioceses). It became a "special daughter of the see of Rome," but without archbishops leading it. In the Late Middle Ages, problems in the Catholic Church allowed the Scottish Crown to have more say in choosing church leaders. Two archbishoprics were set up by the end of the 1400s. Some historians think monasticism declined in the Late Middle Ages. But the mendicant orders of friars grew, especially in the expanding towns. They met the spiritual needs of the people. New saints and ways of showing devotion also became popular. Despite issues with the number and quality of clergy after the Black Death in the 1300s, and some signs of heresy, the church in Scotland stayed fairly stable before the Reformation in the 1500s.

Scotland's Geography and Borders

Modern Scotland is half the size of England and Wales. But with its many inlets, islands, and inland lochs, it has about 4,000 miles of coastline. Only a fifth of Scotland is less than 60 meters above sea level. Its location on the east Atlantic means it gets a lot of rain. Today, it's about 700 cm per year in the east and over 1,000 cm in the west. This led to the spread of peat bogs. Their acidity, along with strong winds and salt spray, made most islands treeless. Hills, mountains, quicksands, and marshes made travel and conquest very difficult. This might have led to fragmented political power.

The main feature of Scotland's geography is the difference between the Highlands and Islands in the north and west and the Lowlands in the south and east. The Highlands are further divided by the Great Glen fault line. The Lowlands are split into the fertile Central Lowlands and the higher Southern Uplands. The Cheviot hills are in the Southern Uplands. The border with England ran over these hills by the end of the period. Some areas were further divided by mountains, large rivers, and marshes. The Central Lowland belt is about 50 miles wide. It has most of the good farmland and easier travel. So, it could support most of the towns and traditional Medieval government. However, the Southern Uplands, and especially the Highlands, were less productive economically. They were also much harder to govern. This gave Scotland a form of protection. Small English attacks had to cross the difficult Southern Uplands. The two major English attempts to conquer Scotland, under Edward I and Edward III, could not get into the Highlands. From there, Scottish resistance could take back the Lowlands. However, these areas were also hard for Scottish kings to govern. Much of the political history after the wars of independence was about trying to solve problems of strong local power in these regions.

Until the 1200s, the borders with England changed a lot. Northumbria was taken by Scotland under David I. But it was lost under his grandson Malcolm IV in 1157. By the late 1200s, the Treaty of York (1237) and Treaty of Perth (1266) set the borders with England and Norway. These were close to today's boundaries. The Isle of Man came under English control in the 1300s, despite Scottish attempts to get it back. The English took a large part of the Lowlands under Edward III. But these lands were slowly regained, especially when England was busy with the Wars of the Roses (1455–1485). The dowry of the Orkney and Shetland Islands in 1468 was the last big land gain for the kingdom. However, in 1482, Berwick, a border fort and the largest port in Medieval Scotland, fell to the English again. This was its final change of hands.

Economy and Society in Medieval Scotland

How People Made a Living

Scotland has about a fifth (15-20%) of the good farming or grazing land of England and Wales. It also has roughly the same amount of coastline. So, raising animals and fishing were two very important parts of the Medieval Scottish economy. With poor roads and communication, most settlements in the Early Middle Ages had to grow their own food. Most farms were run by families. They used a system of infield and outfield farming. Crop farming grew in the High Middle Ages. Agriculture had a good period between the 1200s and late 1400s.

Unlike England, Scotland had no towns from Roman times. From the 1100s, there are records of burghs, which were chartered towns. These became major centers for crafts and trade. There is evidence of 55 burghs by 1296. Scottish coins also existed. But English money was probably more important for trade. Until the end of the period, trading goods directly (barter) was likely the most common way to exchange things. Still, crafts and industry were not very developed before the end of the Middle Ages. Scotland had wide trading networks. But Scots mostly exported raw materials. They imported more and more luxury goods. This led to a shortage of silver and gold coins. It might have helped create a money crisis in the 1400s.

Population Changes

There are almost no written records to figure out the population of early Medieval Scotland. Estimates suggest 10,000 people in Dál Riata and 80,000–100,000 for Pictland. The 400s and 500s likely saw higher death rates due to the bubonic plague. This might have reduced the population. Studying burial sites from this time, like at Hallowhill, St Andrews, shows a life expectancy of only 26–29 years. Conditions suggest it was a society with many births but also many deaths. This is similar to many developing countries today. It meant a relatively young population. Women might have had children early and many of them. This would have meant fewer workers compared to the number of people to feed. This might have made it hard to produce extra food, which would allow the population to grow and more complex societies to develop. From the formation of the Kingdom of Alba in the 900s until the Black Death reached the country in 1349, the population might have grown from half a million to one million. This is based on the amount of farmable land. There are no exact records of the plague's impact. But there are many stories about abandoned land in the decades after. If Scotland followed England's pattern, the population might have fallen to as low as half a million by the end of the 1400s. Compared to later times, these numbers would have been spread fairly evenly across the kingdom. Roughly half lived north of the Tay River. Perhaps ten percent of the population lived in one of the many burghs that grew in the later Medieval period. These were mainly in the east and south. It's thought they had an average population of about 2,000. But many would be much smaller than 1,000. The largest, Edinburgh, probably had over 10,000 people by the end of this era.

How Society Was Organized

How society was organized in the early period is unclear. There are few written records. Family ties probably formed the main way people grouped together. Society was divided into a small group of nobles, who were focused on warfare. There was a larger group of free people, who could carry weapons and were protected by laws. Below them was a relatively large group of slaves. By the 1200s, more records allow us to see clearer social levels. These included the king and a small group of mormaers above lower ranks of free people. There was also likely a large group of serfs, especially in central Scotland. In this period, feudalism (introduced under David I) meant that noble lordships started to overlap this system. English terms like earl and thane became common. Below the nobles were husbandmen with small farms. There were also growing numbers of cottars and gresemen with smaller landholdings.

The mix of family ties and feudal duties is seen as creating the system of clans in the Highlands during this era. Scottish society adopted the idea of three estates to describe its structure. It used English words to tell different ranks apart. Serfdom disappeared from records in the 1300s. New social groups of laborers, craftsmen, and merchants became important in the growing towns. This led to more social tensions in urban areas. But unlike England and France, there was little major unrest in Scottish rural society. There, economic changes were relatively small.

Culture in Medieval Scotland

Languages and Traditions

Modern language experts divide Celtic languages into two main groups. P-Celtic languages include Welsh, Breton, Cornish, and Cumbric. Q-Celtic languages include Irish, Manx, and Gaelic. The Pictish language is a mystery. The Picts had no writing system. All that remains are place names and some inscriptions in Irish ogham script. Most modern experts agree that Pictish belonged to the P-Celtic group, though its exact nature is unclear. Historical records and place names show how Pictish in the north and Cumbric in the south were replaced by Gaelic, Old English, and later Norse during this period. By the High Middle Ages, most people in Scotland spoke Gaelic. It was then simply called Scottish, or in Latin, lingua Scotica. The Kingdom of Alba was mostly an oral society dominated by Gaelic culture. Our better sources for Ireland from the same time suggest there would have been filidh. These were poets, musicians, and historians. They often worked for a lord or king. They passed on their knowledge and culture in Gaelic to the next generation.

In the Northern Isles, the Norse language brought by Scandinavian settlers became Norn. This language lasted until the late 1700s. Norse might also have been spoken in the Outer Hebrides until the 1500s. French, Flemish, and especially English became the main languages of Scottish towns. Most of these towns were in the south and east. Anglian settlers had already brought a form of Old English to this area. In the late 1100s, the writer Adam of Dryburgh described lowland Lothian as "the Land of the English in the Kingdom of the Scots." At least from David I's reign, Gaelic stopped being the main language of the royal court. French probably replaced it. This is shown by reports from chronicles, literature, and translations of official documents into French. After this "de-gaelicisation" of the Scottish court, a less respected group of bards took over the roles of the filidh. They continued to act in a similar way in the Highlands and Islands until the 1700s. They often trained in bardic schools. A few, like the one run by the MacMhuirich dynasty, who were bards to the Lord of the Isles, existed in Scotland. More existed in Ireland. They were stopped from the 1600s. Members of bardic schools learned the complex rules of Gaelic poetry. Much of their work was never written down. What survives was only recorded from the 1500s.

In the late Middle Ages, Middle Scots, often just called English, became the main language of the country. It came mostly from Old English. It also had parts from Gaelic and French. Although it was similar to the language spoken in northern England, it became a distinct dialect from the late 1300s onwards. The ruling class started to use it as they slowly stopped using French. By the 1400s, it was the language of government. Acts of parliament, council records, and treasurer's accounts almost all used it from James I's reign onwards. As a result, Gaelic, once dominant north of the Tay, began to decline steadily. Lowland writers started to see Gaelic as a lower-class, rural, and even funny language. This helped shape attitudes towards the Highlands and created a cultural gap with the Lowlands.

Learning and Schools

When Christianity arrived, Latin became a language for scholars and writing in Scotland. Monasteries were important places for knowledge and education. They often ran schools and created a small group of educated people. These people were essential for creating and reading documents in a society where most people couldn't read. In the High Middle Ages, new types of schools appeared, like song and grammar schools. These were usually connected to cathedrals or large churches. They were most common in the growing towns. By the end of the Middle Ages, grammar schools could be found in all the main towns and some smaller ones. Early examples include the High School of Glasgow (1124) and the High School of Dundee (1239). There were also smaller "petty schools," more common in rural areas, which gave basic education. Some monasteries, like the Cistercian abbey at Kinloss, welcomed more students. The number and size of these schools seemed to grow quickly from the 1380s. They were almost only for boys. But by the end of the 1400s, Edinburgh also had schools for girls. These were sometimes called "sewing schools." They were probably taught by women or nuns. Private lessons also developed in the families of lords and wealthy townspeople. The growing focus on education led to the Education Act 1496. This law said that all sons of nobles and wealthy landowners should go to grammar schools to learn "perfect Latin." All this led to more people being able to read. But this was mostly among wealthy men. Perhaps 60 percent of the nobility could read by the end of the period.

Until the 1400s, those who wanted to go to university had to travel to England or Europe. Just over 1,000 Scots are known to have done so between the 1100s and 1410. Among these, the most important thinker was John Duns Scotus. He studied at Oxford, Cambridge, and Paris. He probably died in Cologne in 1308. He became a major influence on religious thought in the late Middle Ages. After the Wars of Independence began, English universities were closed to Scots, except for special permissions. European universities became more important. Some Scottish scholars became teachers in European universities. At Paris, this included John De Rate and Walter Wardlaw in the 1340s and 1350s, William de Tredbrum in the 1380s, and Laurence de Lindores in the early 1500s. This situation changed with the founding of the University of St Andrews in 1413, the University of Glasgow in 1450, and the University of Aberdeen in 1495. At first, these schools were for training church leaders. But they were increasingly used by ordinary people. These people would start to challenge the church's control over government and law jobs. Those wanting to study for advanced degrees still needed to go elsewhere. Scottish scholars continued to visit Europe. English universities reopened to Scots in the late 1400s. The continued movement to other universities created a group of Scottish thinkers called nominalists in Paris in the early 1500s. John Mair was probably the most important figure. He likely studied at a Scottish grammar school, then Cambridge, before moving to Paris in 1493. By 1497, the humanist and historian Hector Boece, born in Dundee and who had studied in Paris, returned to become the first head of the new University of Aberdeen. These international connections helped Scotland join a wider European scholarly world. They were one of the most important ways new ideas of humanism came into Scottish intellectual life.

Stories and Poems

Much of the earliest Welsh literature was actually written in or near what is now Scotland. It was in the Brythonic language, from which Welsh came. This includes The Gododdin and the Battle of Gwen Ystrad. There are also religious works in Gaelic. These include the Elegy for St Columba by Dallan Forgaill, around 597, and "In Praise of St Columba" by Beccan mac Luigdech of Rum, around 677. In Latin, there is a "Prayer for Protection" (thought to be by St Mugint), around the mid-500s, and Altus Prosator ("The High Creator," thought to be by St Columba), around 597. In Old English, there is The Dream of the Rood. Lines from it are found on the Ruthwell Cross. This makes it the only surviving piece of Northumbrian Old English from early Medieval Scotland. Before David I's reign, the Scots had a strong group of writers. They produced texts in both Gaelic and Latin. This tradition continued in the Highlands until the 1200s. It's possible that more Middle Irish literature was written in Medieval Scotland than often thought. But it might not have survived because the Gaelic writing community in eastern Scotland died out before the 1300s. In the 1200s, French became a popular literary language. It produced the Roman de Fergus, the earliest non-Celtic story to survive from Scotland.

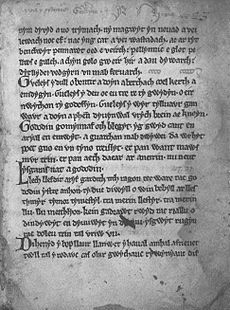

The first major surviving text in Early Scots literature is John Barbour's Brus (1375). It was written with support from Robert II. It tells the epic story of Robert I's actions before the English invasion until the end of the war of independence. Many Middle Scots literary works were created by makars. These were poets connected to the royal court. This included James I (who wrote The Kingis Quair). Many makars had a university education. So, they were also linked to the church. However, Dunbar's Lament for the Makaris (around 1505) shows there was a wider tradition of non-church writing outside of court. Much of this is now lost. Before printing came to Scotland, writers like Robert Henryson, William Dunbar, Walter Kennedy, and Gavin Douglas were seen as leading a golden age in Scottish poetry. In the late 1400s, Scots prose also began to develop. Although there are earlier small pieces of original Scots prose, like the Auchinleck Chronicle, the first complete surviving work is John Ireland's The Meroure of Wyssdome (1490). There were also Scots translations of French chivalry books from the 1450s. These include The Book of the Law of Armys and the Order of Knychthode. Also, the book Secreta Secetorum, an Arabic work believed to be Aristotle's advice to Alexander the Great. The most important work during James IV's reign was Gavin Douglas's version of Virgil's Aeneid, called the Eneados. This was the first complete translation of a major classical text into an Anglian language. It was finished in 1513, but was overshadowed by the disaster at Flodden.

Art and Creativity

In the early Middle Ages, different language groups and kingdoms in what is now Scotland had their own distinct art styles. Pictish art can be seen in many carved stones. These are found especially in the north and east. They show various repeating images and patterns, like at Dunrobin and Aberlemno stones. It also appears in detailed metalwork, mostly found in buried treasures like the St Ninian's Isle Treasure. Irish-Scots art from the Kingdom of Dál Riata is harder to identify. But it might include items like the Hunterston brooch. This, along with other items like the Monymusk Reliquary, suggests that Dál Riata was a place where the Insular style developed. This was a crossroads of cultures. Insular art is the name for the common style that grew in Britain and Ireland. It appeared after the Picts converted to Christianity and their culture blended with that of the Scots and Angles. This style became very influential in Europe. It helped develop Romanesque and Gothic styles. It can be seen in detailed jewelry, often using many semi-precious stones. It's also in the heavily carved High crosses, found most often in the Highlands and Islands, but spread across the country. And especially in the highly decorated illustrated manuscripts like the Book of Kells, which might have been started or fully created on Iona. The best period of this style ended with the disruption to monasteries and noble life caused by Viking raids in the late 700s.

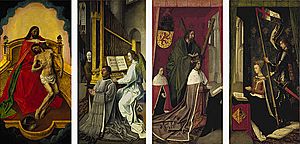

Scotland adopted the Romanesque style in the late 1100s. It kept and revived parts of this style even after Gothic became popular elsewhere from the 1200s. Much of the best Scottish artwork from the High and Late Middle Ages was religious or made of metal and wood. It has not survived the effects of time and the Reformation. However, examples of sculpture exist as part of church buildings. These include detailed church interiors like the sacrament houses at Deskford and Kinkell. Also, the carvings of the seven deadly sins at Rosslyn Chapel. From the 1200s, there are many large memorial statues, like the detailed Douglas tombs in the town of Douglas. Local craftsmanship can be seen in items like the Bute mazer and the Savernake Horn. It's also visible in the many high-quality seals that survive from the mid-1200s onwards. Visual art can be seen in the decorations of official documents. There are also occasional surviving works like the 1400s Doom painting at Guthrie. Surviving copies of individual portraits are quite simple. But more impressive are the works by artists hired from Europe, especially the Netherlands. These include Hugo van Der Goes's altarpiece for the Trinity College Church in Edinburgh and the Hours of James IV of Scotland.

Buildings and Architecture

Medieval local buildings used materials found nearby. These included houses built with cruck frames, turf walls, and clay. Stone was also used a lot. As towns grew, there were more complex houses for nobles, townspeople, and others. By the end of the period, some were built of stone with slate roofs or tiles. Medieval church buildings were usually simpler than in England. Many churches remained simple rectangles, without side sections or aisles. They often had no towers. From the 1000s, English and European designs influenced buildings. Grand church buildings were built in the Romanesque style, as seen at Dunfermline Abbey and Elgin Cathedral. Later, the Gothic style was used, as at Glasgow Cathedral and in the rebuilding of Melrose Abbey. From the early 1400s, Renaissance styles arrived. This included bringing back some Romanesque forms, like in the nave of Dunkeld Cathedral and in the chapel of Bishop Elphinstone's Kings College, Aberdeen (1500–1509). Many of the motte and bailey castles, brought to Scotland with feudalism in the 1100s, were destroyed during the Wars of Independence. These were replaced by "enceinte" castles, with high, battlemented curtain walls. In the late Middle Ages, new castles were built. Some were larger "livery and maintenance" castles, built to house soldiers. Gunpowder weapons completely changed castle design. Existing castles were changed to use gunpowder weapons. This meant adding "keyhole" gun ports, platforms for guns, and walls made stronger to resist bombs. Ravenscraig, started around 1460, is probably the first castle in the British Isles built as an artillery fort. It had "D-shape" bastions that could better resist cannon fire and on which artillery could be mounted. Most late medieval forts in Scotland built by nobles were tower houses. These were mainly for protection against smaller raiding groups, not a major siege. Extensive building and rebuilding of royal palaces in the Renaissance style probably began under James III. It sped up under James IV. Linlithgow was first built under James I. It was called a palace from 1429, apparently the first time this term was used in Scotland. This was expanded under James III. It began to look like a fashionable Italian palace with four sides and corner towers. It combined classical balance with knightly images.

Music and Sounds

In the late 1100s, Giraldus Cambrensis wrote that "many believe Scotland not only equals its teacher, Ireland, but indeed greatly outdoes it and excels her in musical skill." He said the Scots used the cithara, tympanum, and chorus. What these instruments were exactly is unclear. Bards probably played the harp while reciting poetry. They are mentioned in records of Scottish courts throughout the Medieval period. Scottish church music from the 1200s was increasingly influenced by European developments. Figures like the music expert Simon Tailler studied in Paris. He then returned to Scotland and made several reforms to church music. Scottish music collections like the 1200s 'Wolfenbüttel 677', linked to St Andrews, mostly contain French compositions. But they also have some unique local styles. James I's captivity in England from 1406 to 1423 might have led him to bring English and European styles and musicians back to the Scottish court after his release. In the late 1400s, several Scottish musicians trained in the Netherlands before returning home. These included John Broune, Thomas Inglis, and John Fety. Fety became master of the song school in Aberdeen and then Edinburgh. He introduced a new five-fingered organ playing technique. In 1501, James IV rebuilt the Chapel Royal within Stirling Castle. It had a new, larger choir and became the main place for Scottish church music. Influences from Burgundy and England were likely strengthened when Henry VII's daughter Margaret Tudor married James IV in 1503.

Scottish Identity

In the High Middle Ages, the word "Scot" was only used by Scots to describe themselves to foreigners. Among foreigners, it was the most common word. Scots called themselves Albanach or simply Gaidel. Both "Scot" and Gaidel were terms that linked them to most people in Ireland. In the early 1200s, the writer of De Situ Albanie noted: "The name Arregathel [Argyll] means margin of the Scots or Irish, because all Scots and Irish are generally called 'Gattheli'." Scotland gained a unity that went beyond Gaelic, French, and Germanic differences. By the end of the period, the Latin, French, and English word "Scot" could be used for any subject of the Scottish king. Scotland's kings spoke many languages and its nobles were a mix of Gaelic and French-Norman. They all became part of the "Community of the Realm." In this community, ethnic differences were less dividing than in Ireland and Wales. This identity was shaped by fighting against English attempts to take over the country. It was also shaped by social and cultural changes. The resulting dislike of England strongly influenced Scottish foreign policy well into the 1400s. This made it very hard for Scottish kings like James III and James IV to seek peace with their southern neighbor. In particular, the Declaration of Arbroath stated Scotland's ancient uniqueness in the face of English aggression. It argued that the king's role was to defend the independence of the Scottish community. This document is seen as the first "nationalist theory of sovereignty."

The adoption of Middle Scots by the nobles is seen as building a shared sense of national unity and culture between rulers and ruled. However, the fact that Gaelic still dominated north of the Tay might have widened the cultural gap between the Highlands and Lowlands. Scotland's national literature created in the late medieval period used legends and history to support the crown and nationalism. This helped foster a sense of national identity, at least among its educated audience. The epic poems Brus and Wallace helped create a story of united struggle against the English enemy. Arthurian literature in Scotland was different from usual versions. It showed Arthur as a villain and Mordred, the son of the Pictish king, as a hero. The origin story of the Scots, put into order by John of Fordun (around 1320-around 1384), said they came from the Greek prince Gathelus and his Egyptian wife Scota. This allowed them to claim superiority over the English, who said they came from the Trojans, who had been defeated by the Greeks. The image of St. Andrew, who was killed while tied to an X-shaped cross, first appeared in Scotland during the reign of William I. It was also shown on seals used in the late 1200s. This included one used by the Guardians of Scotland, dated 1286. The use of a simple symbol linked to Saint Andrew, the saltire, started in the late 1300s. The Parliament of Scotland ordered in 1385 that Scottish soldiers should wear a white Saint Andrew's Cross on their front and back for identification. The use of a blue background for the Saint Andrew's Cross is said to date from at least the 1400s. The earliest mention of the Saint Andrew's Cross as a flag is in the Vienna Book of Hours, around 1503.