Scottish society in the Middle Ages facts for kids

Scottish society in the Middle Ages was how people lived and worked in what is now Scotland, from when the Romans left in the 400s until the Renaissance began in the early 1500s. For the earliest part of this time, we don't have many written records. So, it's a bit hard to know exactly how society was set up.

It seems that family groups, or kinship groups, were very important. Society was likely divided into a small group of powerful nobles who were mostly warriors. Below them were freemen, who could carry weapons and had rights. Then there was a larger group of slaves. These slaves might have lived with their owners and become like helpers or clients.

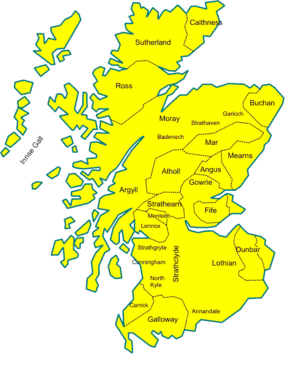

From the 1100s, we have more information. Society had clear levels, with the king at the top. Below him were powerful lords called mormaers. Then came freemen, and a large group of serfs, especially in central Scotland. When King David I brought in feudalism, new lordships were created. English titles like earl became common. Below the nobles were husbandmen (farmers with small farms) and many cottars (people with even smaller plots).

The mix of family ties and feudal rules helped create the clan system in the Highlands. Scottish society also started using the idea of the three estates to describe its groups: those who pray (clergy), those who fight (nobles), and those who work (everyone else). Serfdom slowly disappeared by the 1300s. New groups like workers, craftsmen, and merchants became important in the growing towns called burghs. This led to some arguments in towns. But unlike England and France, Scotland didn't have big peasant revolts. This was because there wasn't much change in how farms were run.

Contents

Early Medieval Society in Scotland

The Early Middle Ages in Scotland lasted from about 400 AD to 1000 AD. During this time, society was changing a lot.

Family Groups and Kinship

In early Medieval Europe, the main way people organised themselves was through their kin group or family. This was probably true in early Scotland too. For the Picts, an ancient people in Scotland, some old writings suggest that leadership might have passed down through the mother's side of the family. This is called matrilineal descent.

However, many historians now think that Pictish society, like other Celtic groups, probably followed the father's side of the family. This is called agnatic descent. They point to evidence that people knew their family lines through their fathers.

Social Classes and Structure

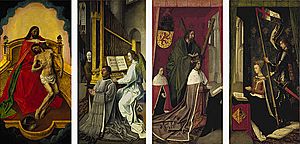

We don't have many records from this time, but we can piece things together. Pictures on stones, like those at Aberlemno and Hilton of Cadboll, show warriors. These images, along with records from Ireland, suggest that the most powerful people in northern Britain were a military aristocracy. Their importance came from their ability and willingness to fight.

Below these nobles were likely freemen. These were people who owned their own small farms or rented them freely. We don't have Scottish law codes from this time. But laws from Ireland and Wales show that freemen could carry weapons. They could also speak for themselves in court and get money if a family member was killed.

Slavery in Early Scotland

It seems that there were many slaves in early Scotland. Slaves were often people captured in wars or raids. They could also be bought, for example, from the Britons in southern Scotland. Even ordinary households probably had some slaves.

Slaves were often taken when they were young. This meant they grew up more connected to their new society than their original one. They would learn the language and culture of their captors. Slaves often lived and worked closely with their owners. This might have made them part of the household. If slaves lived to be older, they often gained their freedom. These freed people might then stay connected to their former owners' families as clients.

Religious Life and Monasteries

Most of what we know about religion in the Early Middle Ages comes from monks. Their writings focus on monastic life. Monks spent their days in prayer and celebrating the Mass. They also farmed, fished, and hunted seals on the islands. Reading and copying books were very important in monasteries. Places like Iona had large libraries. This shows that monks were part of the wider Christian culture in Europe.

Bishops and priests also played a big role, though less is written about them. Bishops worked with local leaders. They ordained new clergy and blessed churches. They also helped the poor, hungry, prisoners, widows, and orphans. Priests performed baptisms, masses, and burials. They prayed for the dead and gave sermons. They also helped the sick and dying.

Early churches were often made of wood. So, we mostly find evidence of them in place names, like those with "cill" or "eccles." Stone crosses and Christian burials also show where churches once stood. Over time, especially on the west coast, these wooden churches were replaced with simple stone buildings.

Learning and Education

In the Early Middle Ages, most people learned by listening and speaking, not by reading. Society was mostly oral. In Ireland, there were filidh. These were poets, musicians, and historians who worked for lords or kings. They passed on their knowledge in Gaelic.

After the 1100s, the Scottish court became less Gaelic. A group called bards took over these roles. They continued to work in the Highlands and Islands until the 1700s. Bards often trained in special schools. Some of these schools were in Scotland, like the one run by the MacMhuirich bardic family. Many more were in Ireland. Much of their work was never written down.

When Christianity came to Scotland, Latin became important for learning and writing. Monasteries were key places for knowledge and education. They often had schools. They also provided a small group of educated people. These people were vital for creating and reading documents in a society where most people couldn't read.

High Medieval Society in Scotland

The High Middle Ages in Scotland was a time of big changes, from about 1000 AD to 1300 AD.

Social Ranks and Titles

A legal document from the time of King David I (1124–53) called Laws of the Brets and Scots shows how important family groups were. It also lists five main social ranks:

- King: The ruler of the country.

- Mormaer: A powerful regional ruler, like a great officer. There were about a dozen of these.

- Toísech: A leader who managed areas of the king's land or a mormaer's land. They had large estates.

- Ócthigern: This means "little lord." They were the lowest rank of free people.

- Neyfs: These were unfree people, like serfs.

Below the nobles, there were many free peasant farmers. They were called husbandmen in the north and south. From the 1100s, landlords encouraged more people to become husbandmen by offering better pay. A new group of free farmers with smaller plots also grew, including cottars and grazing tenants.

The neyfs or serfs were unfree workers. They were tied to a lord's land and couldn't leave without permission. However, records show that many ran away to find better wages or work in towns.

Feudalism and Land Ownership

King David I brought feudalism to Scotland. This was especially true in the east and south, where the king had the most power. Feudalism meant that land was held from the king, or a higher lord. In return, people promised loyalty and military service. New lordships were created, often with castles. Administrative areas called sheriffdoms were also set up.

The English title earl started to replace the Scottish mormaer. However, feudalism didn't completely replace the old ways of owning land. It's not clear how much it changed the daily lives of ordinary free and unfree workers. In some places, feudalism might have tied workers more closely to the land. But because Scottish farming was mostly about raising animals, a system like the English manorial system (where people worked on a lord's estate) might not have worked everywhere. People's duties often included occasional work, giving food, offering hospitality, and paying rent.

Royal Women and Queens

Many of the women we know about from the Middle Ages were part of Scotland's royal family. They were either princesses or queens who married the king. Some of these women became very important.

There was only one reigning Scottish Queen during this time: Margaret, Maid of Norway (ruled 1286–90). She was never crowned and died young. The first wife called "queen" in Scottish records was Margaret, the wife of King Malcolm III. She was an Anglo-Saxon princess. She was a major political and religious figure. But her high status didn't automatically pass to the queens after her.

Ermengarde de Beaumont, the wife of King William I, was a mediator and a judge when her husband was away. She was the first Scottish Queen known to have her own official seal.

Monasteries and Religious Orders

Some early Scottish monasteries had abbots (leaders) who were part of families. This meant the role was passed down. To change this, a group of monks called Céli Dé (meaning "vassals of God") started in Ireland and came to Scotland. Some of these monks promised to live simply and without marriage. Some lived alone as hermits, while others lived in existing monasteries.

Queen Margaret (around 1045–93) helped bring new types of monasteries from Europe to Scotland. She was in touch with the Archbishop of Canterbury. He sent monks for a new Benedictine abbey at Dunfermline. Later, Margaret's sons, especially King David I, founded many new monasteries. These followed the "reformed" style, like those from Cluny Abbey in France. Most belonged to new religious orders that started in France in the 1000s and 1100s. These orders focused on the original Benedictine values: poverty, chastity, and obedience. They also focused on prayer and celebrating the Mass. These included reformed Benedictine, Augustinian, and Cistercian houses. This period also saw the introduction of more complex church architecture, known as Romanesque.

Saints and Their Importance

A big part of Medieval Catholicism was the worship of saints. Saints of Irish origin were especially honoured in Scotland. These included figures like St Faelan and St Colman. Columba remained a very important saint. King William I even gave money for a new church at Arbroath Abbey to honour him. Columba's relics, kept in the Monymusk Reliquary, were given to the abbot there.

Local saints were also important for people's identity. In Strathclyde, St Kentigern (also known as St Mungo) was the most important. His worship was centred in Glasgow. In Lothian, it was St Cuthbert. A new saint, Magnus Erlendsson, became important in Orkney and northern Scotland after his death around 1115.

One of the most important saints in Scotland was St Andrew. His worship began on the east coast at Kilrymont as early as the 700s. People believed the saint's relics were brought to Scotland by Saint Regulus. The shrine began to attract pilgrims from all over Scotland, England, and even further away. By the 1100s, Kilrymont was known simply as St. Andrews. It became strongly linked with Scottish national identity and the royal family. The bishop of St Andrews became the most important bishop in the kingdom. Queen Margaret also became a very important national saint after she was made a saint in 1250. Her remains were moved to Dunfermline Abbey.

Schools and Learning

In the High Middle Ages, new types of schools appeared. These included song schools and grammar schools. They were usually connected to cathedrals or large churches. They were most common in the growing towns. By the end of the Middle Ages, grammar schools could be found in all the main towns and some smaller ones. Early examples include the High School of Glasgow (founded 1124) and the High School of Dundee (founded 1239).

There were also petty schools. These were more common in the countryside. They provided a basic education, teaching reading and writing.

Late Medieval Society in Scotland

The Late Middle Ages in Scotland, from about 1300 AD to 1500 AD, saw more changes in how people lived and were organised.

Family Ties and Clans

Late Medieval Scottish society had strong agnatic kinship. This means people traced their family lines through their fathers. Members of a group often shared a common ancestor, even if it was a made-up one. In the Lowlands, this was often shown by people having the same last name. Unlike in England, where women often took their husband's name, Scottish women kept their original last name when they married. Marriages were meant to create friendships between family groups.

Having a shared last name was a "test of kinship." It meant you had a large group of relatives who could support you. This could make feuds more intense. A feud was a form of revenge for the death or injury of a family member. Large family groups could be relied on to support different sides in a conflict.

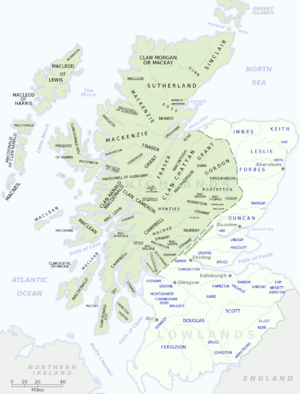

The mix of family ties and feudal rules helped create the Highland clan system. This system is seen in records from the 1200s. In the Highlands, last names were not common until the 1600s and 1700s. In the Middle Ages, not all clan members shared the same name. Most ordinary members were not related to the clan chief. At first, the chief was often the strongest man in the main branch of the clan. Later, it was usually the oldest son of the last chief.

The main families of a clan were called the fine. They were like Lowland gentlemen. They advised the chief in peace and led in war. Below them were the daoine usisle (in Gaelic) or tacksmen (in Scots). They managed the clan lands and collected rents. In the islands and along the west coast, there were also buannachann. These were military elites who defended clan lands and attacked enemies. Most clan followers were tenants. They worked for the clan leaders and sometimes served as soldiers. Later, they would take the clan name as their own last name. This made the clan seem like a huge family group, even if many weren't truly related.

Social Structure and Estates

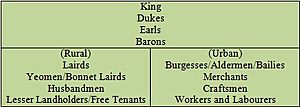

From 1357, the Scottish Parliament started to be called the Three Estates. This was a way of describing society that came from France. The three estates were:

- Clergy: Those who pray (church leaders).

- Nobles: Those who fight (lords and knights).

- Burgesses: Those who work (people from towns).

This showed that people saw Medieval society as having clear, separate groups. Within these estates, the names for different ranks became more like those used in England. Laws were even passed about what weapons and armour people of different ranks should have. There were also laws about what clothes they could wear.

Below the king were a few dukes and earls. These were the highest nobles. Below them were barons, who held land from the king. From the 1440s, lords of Parliament also became important. They were the lowest level of nobility who had the right to attend Parliament. There were about 40 to 60 of these lords in Scotland. Some nobles, especially those who served the king in war or government, could also become knights.

Below these were the lairds. They were similar to English gentlemen. Most lairds served the major nobles. They might hold land from them or have military duties. About half of them shared a name with the nobles and had a distant family connection.

Below the lords and lairds were many different groups. These included yeomen, who often owned a lot of land. Below them were husbandmen, who were smaller landowners and free tenants. They made up most of the working people. Serfdom disappeared in Scotland in the 1300s. However, landlords still had a lot of control over their tenants through local courts.

In the towns, called burghs, the wealthiest merchants were at the top. They often held local offices like burgess or bailie. A few successful merchants were even made knights by the king. This was a special kind of knighthood for town service. Below them were craftsmen and other workers. They made up most of the town population.

Social Challenges and Conflict

Historians have noticed a lot of conflict in the towns between wealthy merchants and craftsmen. Merchants tried to stop craftsmen from taking over their trade and power. Craftsmen tried to show their importance and get into new areas of business. They also tried to set prices and quality standards. In the 1400s, laws were passed that made the merchants' political position stronger.

In the countryside, there isn't much evidence of big revolts like the Jacquerie in France (1358) or the Peasants' Revolt in England (1381). This might be because there wasn't much change in Scottish farming, like the fencing off of common land, that could cause widespread anger. Instead, tenants often supported their landlords in conflicts. In return, landlords helped and supported their tenants.

Both the Highlands and the border areas were known for lawless activities, especially the feud. However, some historians now think that feuds were a way to prevent and quickly solve arguments. They forced people to talk things out, pay compensation, and find solutions.

Popular Religious Practices

Older histories often said the late Medieval Scottish church was corrupt and unpopular. But newer research shows how it met the spiritual needs of different groups. Historians have seen a decline in monastic life during this period. Many monasteries had fewer monks. Those who remained often lived more individual lives instead of communal ones. Nobles also gave less money to new monasteries in the 1400s.

However, in the towns, new groups of friars became popular in the late 1400s. Unlike older monks, friars focused on preaching and helping people. The Observant Friars were organised as a Scottish group from 1467. The older Franciscans and the Dominicans were also recognised as separate groups in the 1480s.

Most Scottish towns usually had only one parish church. As the idea of Purgatory became more important, the number of small chapels, priests, and masses for the dead grew quickly. These were meant to help souls get to Heaven faster. The number of altars dedicated to saints also grew. For example, St Mary's in Dundee had about 48 altars, and St Giles' in Edinburgh had over 50. More saints were celebrated in Scotland too. New ways of worshipping Jesus and the Virgin Mary also came to Scotland in the 1400s.

In the early 1300s, the Pope tried to stop pluralism. This was when one church leader held two or more church jobs. This often meant churches didn't have priests, or had poorly trained ones. But because there were not enough clergy in Scotland, especially after the Black Death, this problem got worse in the 1400s. As a result, parish priests often came from lower, less educated backgrounds. This led to complaints about their education.

Heresy, or beliefs against church teachings, like Lollardry, came to Scotland in the early 1400s. Lollards followed John Wycliffe and Jan Hus. They wanted the Church to reform and disagreed with some of its teachings. Even though some heretics were burned, and there was some support for their ideas, it probably remained a small movement. There were also efforts to make Scottish church services different from English ones. A printing press was even set up in 1507 to print Scottish service books.

Growth of Schools and Universities

The number and size of schools grew quickly from the 1380s. Rich families also started to have private tutors for their children. The focus on education led to the Education Act 1496. This law said that all sons of nobles and wealthy landowners should go to grammar school to learn "perfect Latin." This led to more people being able to read and write. But this was mostly among wealthy men. About 60 percent of nobles could read by the end of this period.

Before the 1400s, anyone who wanted to go to university had to travel to England or Europe. Over 1,000 Scots are known to have done this between the 1100s and 1410. After the Wars of Independence began, English universities were mostly closed to Scots. So, European universities became more important. Some Scottish scholars even became teachers in European universities.

This changed when Scotland founded its own universities:

- University of St Andrews in 1413

- University of Glasgow in 1450

- University of Aberdeen in 1495

At first, these universities were for training church leaders. But more and more ordinary people started to attend. These laymen began to challenge the church's control over government and law jobs. People who wanted to study for higher degrees still went abroad. Scottish scholars continued to visit Europe and English universities, which reopened to Scots in the late 1400s.

Children in Medieval Scotland

Many children died young in Medieval Scotland. Babies were often baptised quickly, sometimes by ordinary people or midwives. This was because people believed unbaptised children would not go to Heaven. Baptism usually happened in a church. It also created a wider spiritual family with godparents.

In one cemetery in Aberdeen, 53 percent of those buried were under six years old. In a Linlithgow cemetery, it was 58 percent. Children often had low iron levels, probably because mothers breastfed for a long time and were also low in minerals. Common childhood diseases included measles, diphtheria, and whooping-cough. Parasites were also common.

In Lowland noble and wealthy families by the 1400s, it became common to use a wet nurse (a woman who breastfeeds another's child). In Highland society, clan leaders often sent their boys and girls to be raised by other chiefs. This was called fosterage. It created a strong, artificial family bond that helped make alliances and mutual duties stronger.

Most children, even in towns where there were more chances for schooling, did not go to school. In craftsmen's families, children probably helped with simpler tasks. They might later become apprentices (learning a trade) or journeymen (skilled workers). In Lowland rural society, many young people, both boys and girls, probably left home to work as servants on farms or in homes. By the late Medieval era, Lowland society likely followed a pattern where young people worked for others for a while. They would then marry later, usually in their mid-20s, after they had saved enough to start their own household.

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |