Elgin Cathedral facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Elgin Cathedral |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Location | Elgin, Moray |

| Country | Scotland |

| Denomination | Catholic |

| History | |

| Authorising papal bull | 10 April 1224 |

| Founded | 1224 (in present position) |

| Founder(s) | Bishop Andreas de Moravia |

| Dedication | The Holy Trinity |

| Dedicated | 19 July 1224 |

| Events |

Pre-Reformation

Post-Reformation

|

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Ruin |

| Architectural type | Cathedral |

| Style | Gothic |

| Administration | |

| Deanery | Elgin Inverness Strathspey Strathbogie |

| Diocese | Moray (est. x1114–1127x1131) |

Elgin Cathedral is a famous old ruin in Elgin, Moray, northeast Scotland. It was built to honor the Holy Trinity. The cathedral was started in 1224 on land given by King Alexander II. It was located just outside the town of Elgin, near the River Lossie.

Before this, the main church was at Spynie, about 3 kilometers north. That church had only eight clerics (church officials). But by 1226, the new Elgin Cathedral had 18 canons, and by 1242, there were 23!

A big fire in 1270 damaged the cathedral, but it was rebuilt even bigger. It survived the Wars of Scottish Independence without harm. However, in 1390, it was badly burned by Alexander Stewart, Earl of Buchan, also known as the Wolf of Badenoch. He was the brother of King Robert III. In 1402, the cathedral area was attacked and burned again by followers of the Lord of the Isles.

Over time, the cathedral grew, and more church workers and builders joined. After the fires of 1270 and 1390, the choir (the part where the clergy sit) became twice as long. New outer aisles were added to both the nave (the main part for people) and the choir. Some walls are still tall, while others are just foundations. But you can still see the original cruciform (cross) shape of the building.

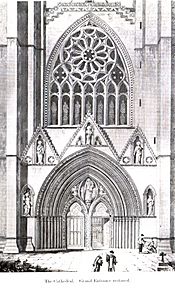

A nearly complete octagonal chapter house (a meeting room for the clergy) was built after the 1270 fire. The gable wall above the main entrance, between the two west towers, was rebuilt after the 1390 fire. It has parts of a large rose window. Inside the transepts (the arms of the cross shape) and the south aisle of the choir, you can find tombs of bishops and knights. The grassy floor also covers old graves marked by flat stones.

The homes of the church leaders and canons, called the chanonry, were also destroyed in the fires. Only the precentor's manse (house) is still mostly standing. Two other houses are now part of private buildings. The two tall west towers, built when the cathedral first started, are mostly complete. A huge wall used to protect the cathedral area, but only two small parts remain. Of the wall's four gates, only the Pans Port is left.

By 1560, when the Scottish Reformation happened, there were 25 canons. After the Reformation, the cathedral was no longer used for services. These services moved to St Giles' parish church in Elgin. In 1567, the lead was removed from the roof to be sold, which started the cathedral's slow decay.

Even though it was mostly whole in 1615, a winter storm in 1637 caused the roof over the eastern part to collapse. In 1711, the central steeple fell, destroying the nave. The Crown took ownership in 1689, but the building kept falling apart. People started trying to save it in the early 1800s, and work continued until the late 1900s, especially on the two western towers.

Contents

Early Church in Moray

The Diocese of Moray was a church region, different from the main Scottish church in St Andrews. It's not clear if there were bishops of Moray before about 1120. The first known bishop was Gregory, who was likely a bishop in name only. He signed important documents between 1123 and 1128.

After a rebellion in 1130, King David I probably felt that having a bishop in Moray was important for keeping the area stable. The next bishop, William (1152–62), was often away. He was King David's helper and probably didn't do much to make the church strong.

Felix was the next bishop (1166–1171), but not much is known about his time. Simon de Toeni, a relative of King William and a former abbot, became bishop after Felix. Bishop Simon was the first to actively manage his diocese. He is thought to be buried near Elgin.

Richard of Lincoln followed Simon. He was a royal clerk who worked hard to increase the church's income. Richard is seen as the first important bishop who actually lived in the area.

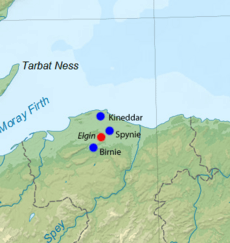

During these early years, the bishops didn't have a fixed place for their cathedral. It moved between churches in Birnie, Kinneddar, and Spynie. In 1206, Pope Innocent III allowed Bishop Brice de Douglas to set his cathedral at Spynie. The new cathedral opened between 1207 and 1208. It had a group of eight clerics, following the rules of Lincoln Cathedral.

Elgin became an important town, possibly because of a new castle there. This might have made Bishop Brice ask the Pope to move the church from Spynie to Elgin before 1216.

Building the Cathedral in Elgin

Even though Bishop Brice wanted to move the cathedral, it wasn't until Bishop Andrew de Moravia's time that it happened. On April 10, 1224, Pope Honorius III gave permission to move the main church to Elgin. The ceremony took place on July 19, 1224. King Alexander II had already agreed to give land for this purpose. This suggests that work on the new church might have started even before the Pope's official approval.

The cathedral was finished after 1242. A writer named John of Fordun said that in 1270, the cathedral and the canons' houses were destroyed by fire. The cathedral was rebuilt even bigger and grander. Most of the building you see today comes from this rebuilding. This work was likely finished before the Wars of Scottish Independence began in 1296. Even though King Edward I of England visited Elgin with his army in 1296 and 1303, the cathedral was not harmed. His grandson, Edward III, also left it untouched in 1336.

After becoming bishop in 1362–63, Bishop Alexander Bur asked Pope Urban V for money to fix the cathedral. He said it had been neglected and attacked. In 1370, Bur started paying protection money to Alexander Stewart, Lord of Badenoch, also known as the Wolf of Badenoch. Buchan was the son of the future King Robert II.

Many disagreements between Bur and Buchan led to Buchan being excommunicated (kicked out of the church) in February 1390. The bishop then sought protection from Thomas Dunbar. In response, Buchan burned the town of Forres in May and Elgin, including the cathedral and its houses, in June. He also likely burned Pluscarden Priory. Bishop Bur wrote to King Robert III, asking for payment for his brother's actions. He described the cathedral as "the particular ornament of the fatherland, the glory of the kingdom, the joy of strangers...".

King Robert III gave Bishop Bur £20 a year for life, and the Pope provided more money from the Scottish Church. In 1402, the town and cathedral area were attacked again, this time by Alexander of Lochaber. He burned the houses but spared the cathedral. Lochaber was excommunicated but later returned to make amends.

Money from church vacancies and customs from Inverness helped with rebuilding. Bishop John Innes (1407–14) made big contributions to the rebuilding. His tomb praises his work. The main changes to the west front were finished before 1435. They show the coat of arms of Bishop Columba de Dunbar (1422–35). The north and south aisles of the choir were probably finished before 1460. The south aisle has the tomb of John de Winchester (1435–60). The last major part to be rebuilt was the chapter house between 1482 and 1501. It shows the arms of Bishop Andrew Stewart.

How the Diocese Was Organized

The chapter was a group of important church officials and canons. Their main job was to help the bishop run the diocese (church region). In Moray, the bishop was just a regular canon in the chapter, and the dean was the leader. This was also true for other Scottish bishops. Every morning, the canons met in the chapter house to discuss church business.

Bishop Brice started with a small chapter of eight clerics. Bishop Andrew de Moravia made it much bigger, adding two senior positions and 16 more canons. By the time Andrew died, there were 23 canons, and two more were added before the Reformation. Churches in church lands or given to the diocese by landowners provided income for the canons. The de Moravia family, Bishop Andrew's family, gave a lot of these gifts.

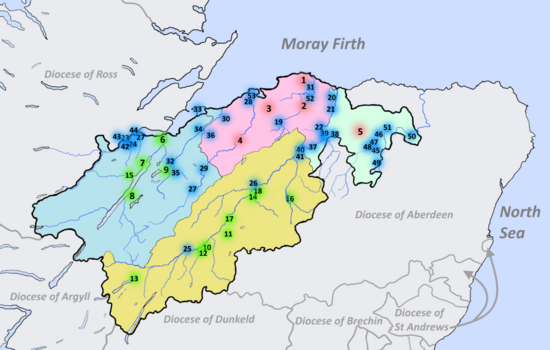

Deans of Christianity were in charge of priests in smaller church areas called deaneries. They made sure the bishop's rules were followed. The Moray diocese had four deaneries: Elgin, Inverness, Strathspey, and Strathbogie. The local churches in these areas provided money for the cathedral and other religious houses.

The bishop was in charge of the diocese, both for church matters and for legal issues. He appointed officials for church, criminal, and civil courts. The bishop, with his chapter, created church laws and made sure they were followed. Courts were held in Elgin and Inverness to deal with things like marriages, divorces, and wills. By 1452, the Bishop of Moray controlled all his lands as one large area, with his own courts to collect money from his estates.

Cathedral Jobs and Roles

Large cathedrals like Elgin had many altars and chapels. They needed canons, helped by many chaplains and vicars, to hold daily services. Bishop Andrew allowed 17 vicars to help the canons. Later, the number of vicars grew to 25. In 1350, the vicars' pay was too low, so Bishop John of Pilmuir gave them income from two churches. By 1489, vicars' pay varied. Each vicar was hired by a canon, who had to give four months' notice if they ended the job.

There were two types of vicars: vicars-choral, who mainly worked in the choir for the main services, and chantry chaplains, who held services at specific altars. The services followed the style of Salisbury Cathedral in England.

Records show that vicars-choral at Elgin were sometimes fined or even physically punished if they didn't perform services well. These punishments happened in the chapter house. King Alexander II started a special service for the soul of King Duncan I, who died near Elgin. The chapel of St Thomas the Martyr was very important. It was in the north transept and had five chaplains. Other chapels were for the Holy Rood, St Catherine, St Duthac, St Lawrence, St Mary Magdalene, St Mary the Virgin, and St Michael. By Bishop Bur's time (1362–1397), the cathedral had 15 canons, 22 vicars-choral, and many chaplains.

Not all clergy were always at Elgin Cathedral. It was common for ambitious clerics to hold positions in other cathedrals too. The dean of Elgin was always there. The precentor, chancellor, and treasurer were there for half the year. Other canons had to attend for three continuous months. In 1240, the chapter decided to fine canons who were often absent by taking away one-seventh of their income. In 1488, many canons didn't follow their leave rules. They were warned, and ten canons who still refused to attend had their income reduced.

Most of the work fell to the vicars and a few permanent canons. They were in charge of high mass, sermons, and feast day processions. Seven services were held daily, mostly for the clergy. These services happened behind the rood screen, which separated the altar and choir from the regular people. Only large churches could perform these elaborate services.

Bishops made sure the cathedral had many educated clerics. These included choir vicars, who could fill in for absent canons, and resident chaplains. Besides religious staff, clerks and lawyers were needed to keep records. Artisans like masons, carpenters, and glaziers maintained the buildings. Housekeepers, cooks, and gardeners also worked to support everyone living in the cathedral area.

The Chanonry and Town

The chanonry, also called the college of the chanonry, was the area around the cathedral. It included the cathedral itself and the homes of the canons, vicars, and chaplains. A strong wall, over 3.5 meters high and about 2 meters thick, surrounded this area. It was about 820 meters long. The wall had four gates:

- The west gate led to the town of Elgin.

- The south gate faced the hospital of Maison Dieu.

- The east gate, or Pans Port, led to a meadow. This gate shows how the gatehouses had defenses like portcullises (Fig. 1).

- The north gate was a shortcut to the bishop's mill and Spynie Palace.

Most houses were inside the wall, but not all. Bishop John Pilmuir (1326-1362) gave land outside the west wall for four chaplains' houses in 1360. These houses were on the road to Elgin. The chaplains were supposed to pray for the bishop's soul. The manse (house) of Rhynie also stood outside the west wall, to the north.

Bishop Andrew Stewart (1482-1501) was an important person during the reign of his nephew, James III. After James III died in 1488, Bishop Andrew spent more time in his diocese. In 1489, he called a meeting of his canons to make needed changes to the college. He approved repairs to the Pans Port and the west gate. He also added a new North Gate near the manse of Botarie. Bishop Andrew ordered thirteen canons, including the archdeacon, to immediately build or repair their houses and gardens within the college.

The Duffus Manse (in its earlier wooden form) hosted two kings: Edward I of England in 1303 and James II in 1455. The precentor's manse, sometimes called the Bishop's House, is partly ruined and dates to 1557 (Fig. 2). Parts of the Inverkeithny and Archdeacon's manses (Fig. 3) are now part of private homes.

There were two friaries (monasteries) in Elgin. The Dominican Black Friars friary was founded around 1233. The Franciscan Grey Friars friary was founded before 1281. This one didn't last long, but another Grey Friars house was built between 1479 and 1513. This building later became the Court of Justice in 1563. In 1489, the chapter started a school. It taught music for the cathedral and also reading to some children of Elgin.

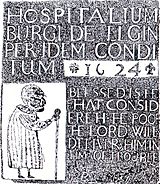

The hospital of Maison Dieu, dedicated to St Mary, was near the cathedral. Bishop Andrew de Moravia founded it before 1237 to help the poor. It was damaged by fire in 1390 and 1445. It eventually fell into disrepair. Bishop James Hepburn gave it to the Blackfriars in 1520 to try and save it. After the Reformation, the Crown took it over. In 1595, James VI gave it to the town for education and charity. It was replaced by an almshouse in 1624 but was ruined in a storm in 1750 and later torn down.

After the Reformation

In August 1560, the Scottish parliament declared the church Protestant. This removed the Pope's power and made Catholic mass illegal. As a result, cathedral buildings only survived if they were used as local churches. Since Elgin already had St Giles' Kirk, its cathedral was abandoned.

On February 14, 1567, parliament ordered the lead to be removed from the roofs of Elgin and Aberdeen cathedrals. This lead was to be sold to support the army. However, the ship carrying the lead to Holland sank in Aberdeen harbor. Regent Moray and Bishop Patrick Hepburn ordered roof repairs in July 1569, but this didn't happen.

In 1615, a writer named John Taylor described Elgin Cathedral as a "fair and beautiful church with three steeples." But he also noted that the roofs, windows, and many tombs were broken.

The decay continued. The roof of the eastern part collapsed in a storm on December 4, 1637. In 1640, the church leaders ordered the rood screen (a partition) to be removed from the choir. It was chopped up for firewood. It's believed that Oliver Cromwell's soldiers destroyed the great west window between 1650 and 1660.

Eventually, the cathedral grounds became a burial place for Elgin. In 1685, the town council repaired the boundary wall, but they specifically said not to use stones from the cathedral. Even though the building was unstable, the chapter house was used for meetings until about 1731. No one tried to stabilize the building, and on Easter Sunday 1711, the central tower collapsed, destroying the nave. After this, stones from the cathedral were taken for other local building projects.

Many artists visited Elgin to draw the ruins. Their drawings show how the cathedral slowly fell apart. By the late 1700s, travelers started visiting the ruin. Pamphlets about the cathedral's history were made for these early tourists. In 1773, Samuel Johnson noted that he received a paper explaining the history of the "venerable ruin."

After bishops were removed from the Scottish Church in 1689, the abandoned cathedral became property of the Crown. But nothing was done to stop its decay. The Elgin Town Council started rebuilding the perimeter wall in 1809 and cleared debris around 1815. In 1824, money was provided to architect Robert Reid to build a new roof for the chapter house. Reid was important in saving historic buildings in Scotland. He became the first head of the Scottish Office of Works in 1827. During his time, buttresses (supports) were added to the choir and transept walls.

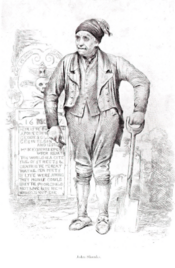

In 1824, John Shanks, a shoemaker from Elgin, began important work to save the cathedral. A local gentleman, Isaac Forsyth, sponsored him. Shanks cleared away centuries of trash and rubble from the grounds. He was officially made the site's Keeper and Watchman in 1826. His work was highly praised, but his methods might have caused some valuable historical evidence to be lost. He died on April 14, 1841, at 82. The Inverness Courier newspaper wrote about him, calling him the "beadle or cicerone of Elgin Cathedral." They said he removed "2866 barrowfuls of earth" and uncovered tombs and figures.

Minor work continued through the late 1800s and early 1900s. In the 1930s, more maintenance was done, including a protective roof for the vaulted ceiling of the south choir aisle. From 1960 onwards, crumbling sandstone blocks were replaced, and new windows were put in the chapter house, which also got a new roof. From 1988 to 2000, major repairs were done on the two western towers. A viewing platform was added to the top of the north tower.

Cathedral Lands and Power

Besides being the church leader, the bishops of Moray were also powerful feudal lords. They owned large areas of land in the Highlands and along the Moray Firth coast. The bishops, with their religious and worldly power, helped the king keep control and stability in a region that was often unsettled.

This important relationship was recognized on November 8, 1451. King James II gave Bishop John Winchester the Barony of Spynie. This allowed the bishop to combine many scattered church lands into one large area. On August 15, 1452, the king made this barony a regality. This gave the bishop wide-ranging powers, including holding courts for crimes that had previously been handled only by the king's sheriff.

Many old documents about land grants were destroyed in the 1390 fire. However, the remaining documents show how the church gained land from royalty and nobles. The 1451 Barony of Spynie charter named most of the church's lands.

Some lands were only discovered when they were rented out or when there were legal disputes. Other records show lands held by important tenants who had to pay homage to the bishop. These actions usually happened when a new bishop was appointed or a new heir took over lands. Even though these were mostly symbolic, they showed how much bishops wanted to keep their power as secular lords. Records also show lands that were once owned by the church but were later rented out. This mainly happened during the troubled times from the mid-1300s to the early 1400s. But even then, bishops strongly defended their rights when lords tried to take church lands.

The bishops kept properties important for themselves and their households. These included areas north of Elgin, like Spynie, where the bishop's palace was, and the nearby Kinneddar. Outside these areas, church lands were spread out. The River Spey flowed into the Moray Firth about 14 kilometers east of Elgin. On its east side were church lands in Strathbogie, including the bishop's barony of Keith. The lands stretched south into the Highlands along the upper reaches of Strathspey, as far south as Logynkenny near the border with Lochaber. West of the Spey, church lands were along the fertile coast between Elgin and Inverness, and down both sides of the Great Glen. The highland areas also had church holdings in Glenfiddich, Strathavon, the Findhorn Valley, Strathnairn, and Badenoch.

How the Cathedral Was Built

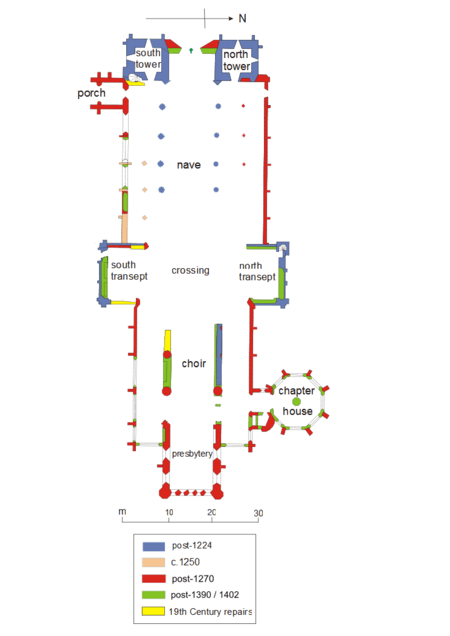

First Construction (1224–1270)

The first church was shaped like a cross and was smaller than the building you see today. This early church had a choir without aisles and a nave with only one aisle on its north and south sides (Fig. 4). The central tower stood above the crossing, where the north and south transepts met. It might have had bells.

The north wall of the choir is the oldest part still standing. It dates from right after the church was founded in 1224. The windows higher up are from the later rebuilding after 1270. This wall has blocked-up windows that go down low, showing it was an outside wall. This proves the eastern part didn't have an aisle back then (Fig. 5).

The south transept's southern wall is almost complete. It shows the excellent work of the first building phase. It has the Gothic pointed arch style in its windows, which appeared in Scotland in the early 1200s. It also has round Norman window designs, which were still used in Scotland during the Gothic period (Fig. 6). The windows and corner stones are made of finely cut sandstone. A doorway in the southwest has large carvings and a pointed oval window above it. Next to the doorway are two tall, narrow windows topped with three round windows. The north transept has less of its original structure left, but old drawings show it was similar to the south transept. It didn't have an outside door and had a stone tower with a staircase.

The west front has two 13th-century towers, 27.4 meters high, with supports. They originally had wooden spires covered in lead. The way the base of the towers and the transepts were built suggests the towers weren't part of the first plan. However, they were added early enough that the builders could connect the nave and towers well (Fig. 7).

Rebuilding After the 1270 Fire

After the fire in 1270, a big rebuilding project started. Repairs were made, and the cathedral was greatly enlarged. Outer aisles were added to the nave. The eastern part, including the choir and presbytery, became twice as long and got aisles on its north and south sides. The octagonal chapter house was built off the new north choir aisle (Figs. 8 & 9).

The new northern and southern aisles ran the length of the choir. They contained tombs set into the walls and chest tombs. The south aisle of the choir had the tomb of Bishop John of Winchester, suggesting this aisle was finished between 1435 and 1460 (Fig. 10). Chapels were added to the new outer aisles of the nave. They were separated by wooden screens. The first section at the west end of these aisles, next to the western towers, didn't have a chapel. Instead, it had a door for regular people to enter.

In June 1390, Alexander Stewart, the Wolf of Badenoch, burned the cathedral, its houses, and the town of Elgin. This fire caused a lot of damage. The central tower had to be completely rebuilt, along with the main arches of the nave. The entire western gable between the towers was rebuilt. The main west doorway and chapter house were also redesigned. The stone carvings inside the entrance are from the late 1300s or early 1400s. They show detailed branches, vines, acorns, and oak leaves.

A large pointed arch opening in the gable, just above the main door, held several windows. The top one was a circular or rose window, built between 1422 and 1435. Above it, you can see three coats of arms: the bishopric of Moray on the right, the Royal Arms of Scotland in the middle, and Bishop Columba Dunbar's shield on the left (Fig. 11).

The nave walls are now very low, or even just foundations. But one section in the south wall is still almost its original height. This section has windows that seem to have been built in the 1400s to replace the 13th-century ones. They might have been built after the 1390 attack (Fig. 12). Nothing of the high parts of the nave remains. But its shape can be seen from the marks where it connected to the eastern walls of the towers. Nothing of the crossing (where the nave and transepts meet) is left after the central tower collapsed in 1711.

Elgin Cathedral is special in Scotland because it has an English-style octagonal chapter house and French-influenced double aisles along each side of the nave. In England, only Chichester Cathedral has similar aisles. The chapter house, which was connected to the choir by a short vaulted room, needed big changes. It now had a vaulted roof supported by a single pillar (Figs. 13 & 14). The chapter house is 10.3 meters high at its peak and 11.3 meters wide. Bishop Andrew Stewart (1482–1501) largely rebuilt it. His coat of arms is on the central pillar. Bishop Andrew was the half-brother of King James II. The long delay in these repairs shows how much damage the 1390 attack caused.

Saving the Ruins (1800s and 1900s)

In 1847–48, some old houses near the cathedral on the west side were torn down. Small changes were made to the boundary wall. Work to strengthen the ruin and rebuild parts began in the early 1900s. This included restoring the east gable rose window in 1904. Missing parts and decorative ribs in the chapter house window were replaced (Fig. 15). By 1913, the walls were re-pointed, and the tops of the walls were waterproofed.

In 1924, the ground level was lowered, and the 17th-century tomb of the Earl of Huntly was moved. More repairs happened in the 1930s. Some 19th-century supports were partly taken down (Fig. 16). Sections of the nave pillars were rebuilt using recovered pieces (Fig. 17). An outside roof was added to the vault in the south choir in 1939 (Fig. 18).

From 1960 to 2000, masons restored the cathedral's crumbling stonework (Fig. 19). Between 1976 and 1988, the window designs of the chapter house were gradually replaced, and its roof was finished (Fig. 20). Floors, glass, and new roofs were added to the southwest tower between 1988 and 1998. Similar restoration work was completed on the northwest tower between 1998 and 2000 (Fig. 21).

Burials

Many important people were buried at Elgin Cathedral:

- Andrew de Moravia – buried in the south side of the choir under a large blue marble stone.

- David de Moravia – buried in the choir.

- William de Spynie – buried in the choir.

- Andrew Stewart (d. 1501)

- Alexander Gordon, 1st Earl of Huntly

- Columba de Dunbar (c. 1386 – 1435) – Bishop of Moray from 1422 until his death.

- George Gordon, 1st Duke of Gordon and his wife Lady Elizabeth Howard.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Catedral de Elgin para niños

In Spanish: Catedral de Elgin para niños