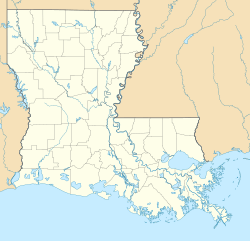

Destrehan Plantation facts for kids

Quick facts for kids |

|

|

Destrehan Plantation

|

|

Destrehan Manor House

|

|

| Location | 13034 River Road, Destrehan, St. Charles Parish, Louisiana |

|---|---|

| Area | Atlanta Georgia |

| Built | 1787–1790 |

| Architect | Charles Paquet |

| Architectural style | French Colonial, Greek Revival |

| NRHP reference No. | 73002132 |

| Added to NRHP | March 20, 1973 |

Destrehan Plantation (French: Plantation Destrehan) is a beautiful old home in Louisiana. It was built before the American Civil War. The house shows off a mix of French Colonial and Greek Revival architecture styles. You can find it in southeast Louisiana, near the town of Destrehan.

In the 1800s, this plantation was very important. It grew a lot of indigo plants, which were used to make blue dye. Later, it became a big producer of sugarcane. The home is most famous for its second owner, Jean Noel Destréhan. He was one of the first United States Senators from Louisiana in 1812. He helped Louisiana become a U.S. state.

What makes Destrehan Plantation special is that it survived even when an oil refinery was built around it. Today, it is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. This is because of its amazing architecture and its connection to important people and events in Louisiana's past.

Exploring Destrehan Plantation's Past

Building a Dream: Robert Antoine Robin de Logny

Destrehan Plantation is one of the oldest homes in Louisiana. Its construction started in 1787 and finished in 1790. This was when Spain ruled Louisiana. Robert Antoine Robin de Logny hired Charles Pacquet, a skilled carpenter who was a free person of color. Pacquet was tasked with building a "raised house" in the Creole style. This style was common in the West Indies.

Pacquet used six workers to help build the home. When the house was finished, he received payment for his hard work. This payment included land, animals, food, and money. The original building contract is still kept safe today. It shows that Destrehan Plantation is the oldest documented house in the lower Mississippi River Valley.

A New Owner: Jean-Noël Destréhan's Era

After Robert de Logny passed away in 1792, his son-in-law, Jean Noël Destréhan, bought the plantation. Jean-Noël had married Marie-Claude Céleste Eléonore Robin de Logny in 1786. They had 14 children! To make room for their large family, two extra wings were added for their sons. The ground floor was also enclosed to create more space.

In the 1790s, the indigo crops failed. So, Destréhan started growing sugarcane instead. His brother-in-law, Étienne de Boré, found a way to make sugar profitable. Destrehan Plantation quickly became the top sugar producer in its area by 1803.

After the Louisiana Purchase, the area became a U.S. territory. Destrehan Plantation was involved in a major event called the 1811 German Coast Uprising. This was a large protest by enslaved people. Jean-Noël Destrehan was part of a group that questioned the people involved.

Trials were held in different places, including at Destrehan Plantation. The justice system at that time was based on old French laws. These laws did not always offer fair trials.

A Controversial Will: Stephen Henderson's Story

After Jean-Noël Destréhan died in 1823, the plantation changed hands again. Two years later, his son-in-law, Stephen Henderson, bought it. Henderson was from Scotland and had become very rich as a businessman. In 1816, he married Marie Eléonore "Zelia" Destréhan, who was 16. Destrehan Plantation was Zelia's childhood home.

Zelia passed away in 1830 without having children. Stephen Henderson was very sad and died eight years later. His will caused a lot of discussion at the time. He wanted all the enslaved people he owned to be freed. He also offered them a chance to travel to Liberia if they wished. For those who stayed, he planned to set up a factory for them to make shoes and clothes.

Henderson's family disagreed with his will. After 12 years of legal battles, the will was set aside. This happened because of a legal detail.

Changes and Challenges: Pierre Adolphe Rost's Time

Pierre Adolphe Rost, a judge on the Louisiana Supreme Court, bought the plantation in 1839. He and his wife, Louise Odile Destréhan, were also part of the Destréhan family. They began to update the house in the popular Greek Revival style. They added new details to doors and windows. The wooden columns were covered in plastered brick. The back porch was enclosed to create a new entrance.

When the American Civil War began, Rost offered his help to the Confederate States of America. He became a representative in Spain and lived there with his family during most of the war. After the war ended in 1865, the government took over the plantation. It became the Rost Home Colony. This colony aimed to help newly freed people. They could get medical and educational help. They also worked for wages or a share of the crops. The Rost Home Colony was very successful in Louisiana.

In 1865, Pierre Rost returned from Europe. He received a pardon from President Andrew Johnson and asked for his property back. The Colony continued for another year, paying rent to Rost. The last people left the colony in December 1866.

Pierre Rost died in 1868. His wife and son, Emile Rost, continued to live at Destrehan Plantation. Emile Rost sold the plantation in 1910. This ended 123 years of family ownership.

The Oil Company Era and Decay

In 1914, the Mexican Petroleum Company bought the property. This company later became part of the American Oil Company. They built an oil refinery on the land. Many of the smaller buildings around the main house were torn down. The mansion itself was used for different things, including as a club for employees.

In 1959, American Oil closed the refinery and left the site. For the next 12 years, Destrehan Plantation fell into disrepair. People looking for treasure damaged the walls. There was an old story that the privateer Jean Lafitte had hidden treasure there. Vandals also stole valuable items from the house. They took marble mantels, cypress wood panels, Spanish tiles, and window glass.

Luckily, a local sheriff stopped the theft of the plantation's original iron entrance gates from the 1840s. He also saved a large 1,400 lb (640 kg) marble bathtub. It was rumored that this bathtub was a gift from Napoleon Bonaparte to the family.

Bringing History Back to Life: River Road Historical Society

In 1971, American Oil gave the house and 4 acres (16,000 m2) of land to the River Road Historical Society. This is a group that works to preserve history. The oil company continued to help in 1990. They donated money for a fire sprinkler system and a new roof. They also gave an additional 12.8 acres (52,000 m2) of land.

Thanks to many volunteers, the historical society raised enough money to stop the decay. They restored the house and its grounds to their former beauty. Recently, they have been working to rebuild the plantation community. This includes the smaller buildings that would have surrounded the main house.

Destrehan Plantation is open every day for guided tours. These tours teach visitors about the lives of everyone who lived there, both free and enslaved. You can often see demonstrations of old crafts. These include dyeing with indigo, making candles, and cooking over an open fire.

More to Learn

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |