Doina Cornea facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Doina Cornea

|

|

|---|---|

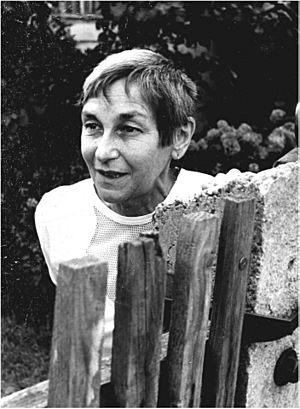

Cornea in the 1980s

|

|

| Born | 30 May 1929 |

| Died | 3 May 2018 (aged 88) |

| Resting place | Hajongard Cemetery, Cluj-Napoca |

| Citizenship | Romanian |

| Alma mater | Babeș-Bolyai University |

| Occupation | Human rights activist Language professor |

| Years active | 1949–2018 |

| Known for | Dissident in Communist Romania led by Nicolae Ceaușescu |

|

Notable work

|

translation of Încercarea Labirintului by Mircea Eliade |

| Political party | National Salvation Front (1989–1990) Romanian Democratic Convention (1990–2000) |

| Board member of | Group for Social Dialogue |

| Children | Ariadna Combes Leontin Juhasz |

| Awards | See Honours and awards |

Doina Cornea (30 May 1929 – 3 May 2018) was a brave Romanian woman. She was a professor of French language and a human rights activist. She became famous for speaking out against the communist government of Nicolae Ceaușescu in Romania. People who spoke out against the government were called dissidents.

After the communist rule ended, Doina Cornea helped start the Democratic Anti-totalitarian Forum of Romania. This group was the first to try and unite people who wanted a democratic government. Later, this group became the Romanian Democratic Convention (CDR). This political group helped Emil Constantinescu become president of Romania.

Contents

Early Life and First Steps in Activism

Doina Cornea was born in Brașov, Romania. In 1948, she began studying French and Italian at the University of Cluj. After finishing her studies, she taught French in a school in Zalău. She married a lawyer there. In 1958, she moved back to Cluj. She became an assistant professor at Babeș-Bolyai University.

Her journey into political activism began in 1965. She was in France and saw a friend openly criticize a leader, Charles de Gaulle. Doina expected her friend to be arrested, but nothing happened. This made her feel ashamed of the strict rules in Romania. This feeling pushed her to start fighting for freedom.

Speaking Out Against Communism

In 1980, Doina Cornea published her first samizdat book. A samizdat was a book copied and spread secretly because the government didn't allow it. Her book was a translation of Încercarea Labirintului ("The Test of the Labyrinth") by Mircea Eliade. She then secretly translated four more books.

Protest Letters to the World

In 1982, she secretly sent a letter to Radio Free Europe. This was the first of many letters and protests she sent against Ceaușescu's rule. She believed Romania faced a crisis. It was not just about money, but also about people's spirits. She felt Romanians cared too much about things and not enough about ideas like intelligence, ethics, culture, and freedom.

At the end of her first letter, she signed her name. She did this to show the letter was real. But she asked them not to say her name out loud. By mistake, Radio Free Europe read her name on air. Because of her political actions, she was fired from the university on September 15, 1983. The official reason was that she gave her students a diary by Mircea Eliade to read.

She sent a second letter, which was broadcast by BBC and Radio Free Europe. In this letter, she protested against the strict rules at universities. She also criticized how the university leaders did not support her. She kept sending many letters and protests to Radio Free Europe. She believed that even if the government changed, people's bad habits might not.

In August 1987, she wrote an open letter to Ceaușescu. She asked for big changes in universities. She wanted more academic freedom and for universities to be independent. This would stop them from being controlled by the Romanian Communist Party. She also wanted more student exchanges with foreign universities. She believed students should learn how to think, not just memorize facts.

During the Brașov rebellion on November 18, 1987, Doina Cornea and her son, Leontin Iuhaș, spread 160 manifestos in Cluj-Napoca. These papers showed support for workers who protested against the communist government. The next day, the secret police, called the Securitate, arrested them. They were held until December 1987. They were released after many countries protested. A French TV show also broadcast an old interview with Doina Cornea.

In the summer of 1988, she heard on Radio Free Europe that she was invited to a human rights meeting in Cracow. But she never received the invitation. She asked for a passport to travel but was refused. She wrote another letter, saying that a totalitarian society can only succeed by stopping people from thinking freely.

Under House Arrest

Doina Cornea wrote another important letter. It was secretly taken out of the country by a journalist named Josy Dubié. Radio Free Europe broadcast it on August 23, 1988. In this letter, she blamed Ceaușescu for Romania's problems. She told him he had two choices. He could either step down from power, or he could make changes. These changes would allow different political ideas and separate the government from the Communist Party.

She argued for freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom of assembly, and freedom of travel. For the economy, her letter suggested closing factories that lost money. She also wanted factories to be updated to compete with foreign companies. She even suggested hiring foreign managers and bringing back private land ownership. She also wanted to stop the Systematization program, which destroyed villages.

After this, the Securitate put her under house arrest. This meant she could not leave her home. A TV show in Belgium about her led to a worldwide campaign for her release. The European Parliament and other groups passed resolutions asking for her freedom. Important politicians from other countries, like Laurent Fabius and Valéry Giscard d'Estaing from France, and Leo Tindemans from Belgium, spoke to the Romanian government about her.

Even under house arrest, she managed to send two more letters. In one, she wrote that the actions against her were unfair and illegal. She pointed out that the government did not follow its own laws.

In 1989, Doina Cornea was invited to France. Danielle Mitterrand, the wife of French President François Mitterrand, invited her to a celebration of the French Revolution. But Doina was not allowed to leave Romania. Another invitation to the Council of Europe also did not reach her.

Freedom at Last

Doina Cornea was finally released on December 21, 1989. This was during the Romanian Revolution of 1989. It was the day before the communist government was overthrown. As soon as she was free, she joined the street protests in Cluj-Napoca.

After the Revolution

After December 22, 1989, Doina Cornea was asked to join the first new government group, the National Council of the National Salvation Front. But she left this group on January 23, 1990. She left because the group decided to become a political party and run in the 1990 elections. She felt it was still too connected to the Soviet Union and had too many people who were part of the old communist system.

Doina Cornea continued to speak out against the new government led by Ion Iliescu. She did this with other thinkers like Ana Blandiana and Mihai Șora. She helped create the Democratic Anti-totalitarian Forum of Romania. This group aimed to unite those who opposed the new government. It later became the Romanian Democratic Convention (CDR), which helped Emil Constantinescu become president in 1996.

She also helped start other important groups in Romania. These included The Group for Social Dialogue, the Civic Alliance Foundation, and the Cultural Memory Foundation.

Later Life and Legacy

Doina Cornea passed away on May 4, 2018, at her home in Cluj. She was 88 years old. Her son was with her. She was buried with military honors at the Hajongard Cemetery in Cluj. She had two children, Ariadna Combes and Leontin Iuhas. Doina Cornea is remembered as a brave voice for freedom and human rights in Romania.

Honours and Awards

Doina Cornea received many important awards and honours for her courage and work.

Honours

From the Romanian Royal Family: She was made the 40th Knight of the Royal Decoration of the Cross of the Romanian Royal House.

From the Romanian Royal Family: She was made the 40th Knight of the Royal Decoration of the Cross of the Romanian Royal House. From the Romanian Republic: She was a Grand Cross of the Order of the Star of Romania.

From the Romanian Republic: She was a Grand Cross of the Order of the Star of Romania. France: She was made a Commander of the Legion of Honour, which is a very high award in France.

France: She was made a Commander of the Legion of Honour, which is a very high award in France.

Awards

Belgium

Belgium

Brussels: She received an Honorary Degree from the Free University of Brussels.

Brussels: She received an Honorary Degree from the Free University of Brussels.

Norway: She was given The Professor Thorolf Rafto Memorial Prize.

Norway: She was given The Professor Thorolf Rafto Memorial Prize.

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |