Dora Ohlfsen-Bagge facts for kids

Dora Ohlfsen (born August 22, 1869 – died February 7, 1948) was an Australian sculptor and artist who made medals. She mostly worked in Italy. Her first famous work was a bronze medal called The Awakening of Australian Art (1907). It won an award in London in 1908 and was bought by a museum in Paris.

Other important works include the Anzac Medal (1916). This medal helped raise money for Australian and New Zealand soldiers who fought in World War I. She also created Sacrifice (1926), a war memorial in Formia, Italy.

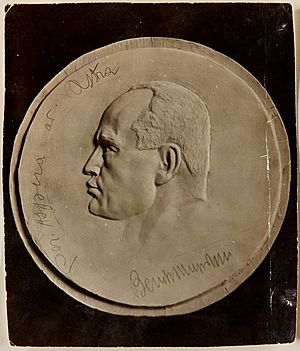

Dora Ohlfsen also made many portrait medals for famous people. These included the actor Mary Anderson and the poet Gabriele D'Annunzio. She also made portraits of important leaders like H. H. Asquith, David Lloyd George, Billy Hughes, and Mussolini. Mussolini even let her sketch him while he worked in 1922.

Contents

Early Life and Learning

Dora Ohlfsen was born in Ballarat, Victoria, Australia. She was the fourth of seven daughters. Her mother, Kate, was Australian, and her father, Christian, was an engineer from Poland with Norwegian family.

Her family was well known. Her grandfather was the first government printer in Victoria. Her father made money during the Victorian gold rush. He also helped build important buildings like the Olympic Theatre in Melbourne.

When Dora was 14, her family moved to Sydney. She went to Sydney Girls High School from 1884 to 1886. A newspaper described her as a "tall, willowy girl" with "beautiful dark eyes." Around 1888, she started learning piano from a French pianist named Henri Kowalski. She even performed at a theatre in 1889. In 1893, a newspaper praised her piano playing, saying her "touch was clear and sparkling."

Around 1892, Dora decided to study music in Berlin, Germany. Friends and important people helped her pay for this. She left Sydney for Germany in December 1892.

Time in Europe: Berlin and Russia

Much of what we know about Dora's time in Europe comes from her own letters. Sometimes, her stories had small differences. A historian named Ros Pesman said that Dora or the journalists might have made her life sound more exciting.

In Berlin, Dora studied at a music academy. She said she even played for the Kaiser. But she had to stop playing piano because of health problems. She called it "neuritis" in her arm or a "nervous breakdown" from working too hard. Her father also had trouble sending money because of an economic problem in Australia.

After her piano career ended, she visited friends in Russia. There, she met Hélène de Kuegelgen, a Russian countess, who became her close companion. By 1896, Dora was trying to make a living in St. Petersburg. She taught music and worked as a private secretary for the American ambassador. She even wrote articles about Russia for American newspapers. She also started studying painting and sculpture. She said the Empress of Russia bought one of her painted items. Dora also became interested in theosophy, a spiritual belief, and said spiritual voices told her to become an artist.

Moving to Rome

Her Studio in Rome

Dora and Hélène moved to Rome, Italy, in 1902. They were worried about the 1905 Russian Revolution starting. Dora said Italy's air "breathes the cameraderie and Bohemianism which every artist craves." In Rome, Dora said she took painting classes and sculpture lessons. She learned from famous artists like Paul Landowski, who created the Christ the Redeemer statue. She also learned from Pierre Dautel, who was very good at making medal portraits.

The women settled into a studio and apartment at Via di S. Nicola da Tolentino 72. This street was a popular place for artists and writers. Famous people like Louisa May Alcott, who wrote Little Women, also lived nearby. Dora's studio became a place where artists, writers, and important people would gather every week.

Making portraits on medals became popular in Europe. Hélène helped Dora get commissions. In 1903, Dora showed three of her paintings in Rome. She also showed her bas-reliefs (sculptures that stick out slightly from a flat surface) in 1905, 1906, and 1907. Her works included medals of Hélène de Kuegelgen and the actor Mary Anderson. She also made one of the famous Australian singer Nellie Melba.

In 1907, an art historian praised Dora's "delightful bas-reliefs in bronze." He said they were made with "tremendous grace and subtlety."

-

Plaque on the building for Augustus Saint-Gaudens

The Awakening of Australian Art (1907)

Dora's first artwork to be bought by a public museum was The Awakening of Australian Art (1907). This was a bronze medal. The French government bought it in 1907 for the Petit Palais museum. The medal shows Australia as a young woman rising from the sea. The back of the medal shows a peaceful scene with sheep and a shepherd. One reporter said it showed "the whole soul and spirit of wide spaces."

In June 1908, the medal won an award at an exhibition in London. A few months before, a magazine in Rome praised Dora's work. It said her medals had a "vibrant spirit of life."

The Art Gallery of New South Wales in Australia bought a copy of The Awakening of Australian Art in 1910. Dora used different ways to make her medals. For The Awakening, she likely used a special machine. She would create a large design, then the machine would copy it in a smaller size.

Another medal Dora made was Femminismo (around 1908). It showed a women's march in London. On the back, a woman was lifting a veil from her eyes. This medal was very popular with women in Paris.

Visit to Sydney (1912–1913)

By 1912, Dora's art was highly respected. In 1909, she was the first Australian to be included in a book about medal artists. She returned to Australia for 15 months in July 1912. She had said in 1908 that she missed Australia very much.

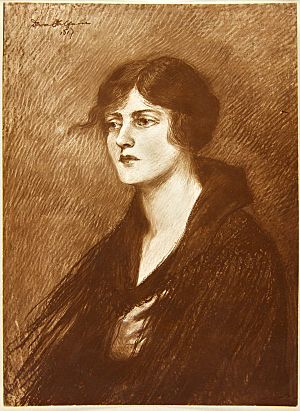

The Art Gallery of New South Wales bought five of her artworks. She showed 20 pieces at an exhibition in Sydney. One of these was a medal portrait of Hélène de Kuegelgen. A newspaper described Hélène as a "woman of noble elegance." In June 1913, Dora's bronze medals of Shakespeare and Goethe were put on display in a theatre. After Sydney, she also had an exhibition in Melbourne.

Art Gallery of New South Wales Commission (1913)

Dora faced a big disappointment during her visit to Australia. The Art Gallery of New South Wales asked her in 1913 to create large bronze panels for the front of the building. These panels would be 24 feet long and 4.5 feet high. She decided to show a chariot race. She returned to Rome in October 1913 to work on it.

Dora wanted the sculpture to show a lot of movement, even from far away. She sent photos of her finished plaster model to the gallery. But in September 1919, the gallery cancelled the project. There were disagreements about the cost of the bronze and the design. Dora was very upset. She felt it would hurt her reputation.

The space above the gallery's entrance remained empty for over 100 years. In 2019, the gallery held an exhibition about Dora Ohlfsen and this cancelled project.

Anzac Medal (1916)

During World War I (1914–1918), Dora and Hélène became Red Cross nurses. Dora helped care for injured people after an earthquake in Italy. She also worked in a hospital in Rome.

In October 1916, Dora created her most famous work in Australia: the Anzac Medallion. It was made to remember and help soldiers from the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (Anzac) who fought in the war. Sixty thousand Australian soldiers died in World War I.

The front of the medal shows a young woman, representing Australia, placing a laurel wreath on a young man's head. The back shows an Anzac soldier with a rifle. It says "Anzac. In Eternal Remembrance. 1914–18." The woman on the medal was based on a 21-year-old named Alexandra Simpson. Dora said she made "Australia" and her "son" (the soldier) very young to represent the "youngest country and the youngest army."

A museum expert called the medal "one of the most remarkable of all Australian commemorative medals." It was praised for its skill and deep feeling.

Dora sold hundreds of these medals to raise money for injured Australian and New Zealand soldiers. The first medal was given to Edward, Prince of Wales. Several Anzac medals are now in museums in Australia.

The front of Dora's Anzac image (the woman and the soldier) is also on a plaque at the Mornington Soldier's Memorial in Australia. This memorial was dedicated in 1925.

Visit to Sydney (1920–1922)

To help sell the Anzac Medal, Dora visited Australia again in 1920. She set up a studio in Sydney. She showed many of her works there. These included Mrs. Grey (1917), a painting of Alexandra Simpson, who was the model for the Anzac medal. She also showed The Awakening of Australian Art and portraits of important leaders.

A writer who met her in 1922 described her as "tall and of one figure." The writer said Dora had a "commanding presence" and a beautiful voice with an Italian accent.

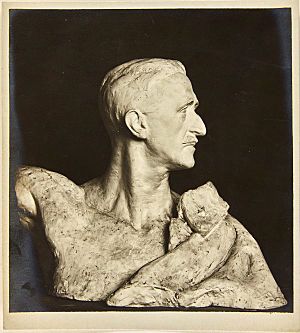

During this visit, Dora also made medals of Australian Prime Minister Billy Hughes (1921) and a bust (a sculpture of the head and shoulders) of actress Nellie Stewart (1922). She had hoped to fix the problem with the Art Gallery of New South Wales commission. She said the gallery was waiting for bronze to be cheaper.

Dora thought about staying in Australia but decided to return to Rome in February 1922. Before she left, she gave a talk about "Futuristic art." She said it was about "sweeping away every canon of art" to fix problems in modern art.

Mussolini Medallion (1922)

| Obverse | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Design | (Top) Ohlfsen holding her Mussolini medallion and (above) plaster cast of the medallion, signed by Mussolini and photographed by Ohlfsen in 1925. |

| Reverse | |

| Design | Unknown |

In 1922, Dora was asked to create a medal of Benito Mussolini. He became the Prime Minister of Italy in October 1922. Mussolini allowed her to sketch him while he worked. He even signed the plaster model of the medal.

Dora was in the crowd during the March on Rome in October 1922 when Mussolini's group took power. She wrote about watching 100,000 Fascists march past a tomb. She described Mussolini as a "man quite above the ordinary" who "positively exudes magnetism." She said he spoke many languages and had a "beautiful voice."

Mussolini's group became a source for many of Dora's art projects. Her art often showed strong, ideal figures, celebrating national pride.

Sacrifice (1926)

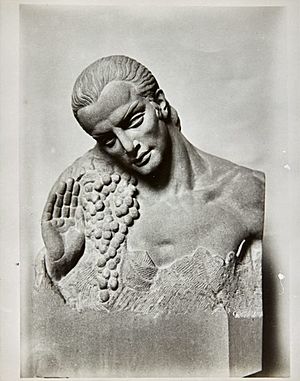

Around 1923, the Italian government asked Dora to create a war memorial in Formia, a town on the coast. This happened because of her friendship with Duke Fulco Tosti di Valminuta, who worked for the government. At the time, Dora was reportedly the only woman and the only non-Italian to get such a commission.

The sculpture, called Sacrifice, is 30 feet tall. It shows a young man made of bronze standing on a white marble base with his arms out. On the base, a woman holds a palm and a laurel branch. She leans towards the names of those who died in World War I. The words on it mean: "Oh, my country! The life thou gave me I return to thee."

The memorial was unveiled in July 1926. Thousands of people attended. Dora was given the Freedom of the City and a silver shield. She described the ceremony in a letter, mentioning the bands playing and people cheering her name.

Historians say Dora's choice of materials and the way she showed sacrifice and care fit well with the ideas of the time. Mussolini reportedly told Dora, "you may now be considered an Italian sculptress." Sadly, the Formia memorial was taken down in 1941. But it was put back together in 2008.

Later Work

In 1930, Dora was asked to submit sketches for sculptures for a memorial in Melbourne, Australia. She was disappointed with the small request. Her ideas for this project did not go beyond a plaster model.

Visitors to Rome still came to Dora's studio. In 1935, a writer described her studio as a "big room high up in a corner." It was filled with sculptures, some covered in cloth, looking like "ghosts in fading light."

When another writer visited in 1933, Dora's large plaster model of the chariot race was hanging on the wall. The room was full of sculptures, including a relief of the Greek god Dionysus. Dora was working on a mural of Francis of Assisi with Australian birds. The writer described Dora as "tall and graceful with remarkable hands."

Death

Not much was heard from Dora during World War II (1939–1945). She was upset when the Formia war memorial was taken down in 1941. After Mussolini's group lost power, Dora had less work. She and Hélène had to sell their belongings to make money.

On February 7, 1948, Dora and Hélène were found dead in their apartment. The police said it was an accident caused by a gas leak. They were buried together in the non-Catholic cemetery in Rome. Dora's sculpture of Dionysus is on their tombstone. The words on it say they were "inseparable friends" who found "eternal rest together."

Collections

Dora Ohlfsen's artwork can be found in museums and galleries in:

- Australia: Australian War Memorial, National Library of Australia, and National Gallery of Australia in Canberra; the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Powerhouse Museum, and University of Sydney in Sydney; the National Museum of Victoria in Melbourne; and the Art Gallery of Ballarat.

- France: the Petit Palais in Paris.

- United Kingdom: the British Museum in London, the University of Glasgow, and the National Library of Wales in Aberystwyth.

Exhibitions After Her Death

- Through Women's Eyes, Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 1994–1995.

- Beyond the Picket Fence: Australian women's art in the National Library collections, National Library of Australia, Canberra, 1995.

- Review: Speaking of Women, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1995.

- Dora Ohlfsen and the façade commission, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2019–2020.

Images for kids

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |