Dunbar Hotel facts for kids

|

Somerville Hotel

|

|

Dunbar Hotel, 2008

|

|

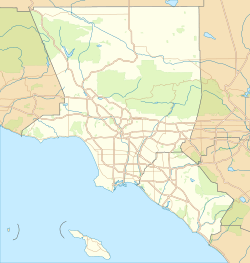

| Location | 4225 S. Central Ave., Los Angeles, California |

|---|---|

| Built | 1928 |

| Architectural style | Mission/Spanish Revival |

| NRHP reference No. | 76000491 |

Quick facts for kids Significant dates |

|

| Added to NRHP | January 17, 1976 |

The Dunbar Hotel, first called the Hotel Somerville, was a very important place for the African-American community in Los Angeles, California. This was especially true during the 1930s and 1940s. It was built in 1928 by John Alexander Somerville. When it first opened, it hosted the first national meeting of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) ever held in the western United States.

In 1930, the hotel was renamed the Dunbar. It quickly became the most famous hotel in Los Angeles for the African-American community. A nightclub opened there in the early 1930s, making it the heart of the Central Avenue jazz scene. Many jazz legends like Duke Ellington, Billie Holiday, and Louis Armstrong performed or stayed there. Other famous people, including W. E. B. Du Bois and Thurgood Marshall, also visited. Today, the building is no longer a hotel. It was updated in the 2010s and is now part of a living community called Dunbar Village.

Contents

The Somerville Hotel: A New Beginning in 1928

The hotel was built in 1928 by John and Vada Somerville. They were important Black leaders in Los Angeles. Vada Somerville was the first African-American woman in California to earn a dental degree from the University of Southern California. John Alexander Somerville was the first Black person to graduate from the same university. The hotel was special because it was built entirely by Black contractors, workers, and artists. Black community members also helped pay for it.

For many years, the Somerville was the only big hotel in Los Angeles that welcomed Black guests. It quickly became the main place for important Black visitors to stay. In 1928, it hosted delegates for the first NAACP convention in the western United States. In 1929, when Oscar Stanton De Priest (the first African American in Congress in the 20th century) visited Los Angeles, he was welcomed with a big parade that led him to the hotel.

The hotel was known for its beautiful design. Its Art Deco lobby had a stunning chandelier, Spanish-style windows, tiled walls, and a stone floor. People said the lobby looked like a "regal Spanish arcade" and was very grand. Someone who was there when it was being built called it "a palace" compared to other places they knew.

The hotel became a symbol of achievement for the Black community. A historian named Lonnie G. Bunch III said that even though Black people were not allowed in major hotels, they could build their own grand hotel with enough money and community spirit. Unlike older segregated hotels, the Somerville offered fancy features like a restaurant, a lounge, and a barbershop. Roy Wilkins wrote that the hotel's luxury and service were "just the opposite of what we had come to expect in 'Negro' hotels."

The Somerville, and later the Dunbar, also helped create the new Central Avenue community. Before 1928, the Black community in Los Angeles was mainly around 12th Street. Somerville was the first to build a large building further south, and soon other businesses followed.

After the stock market crashed in 1929, Somerville had to sell the hotel to a group of white investors. This was sad for the community, as the hotel was a symbol of Black success. The hotel was renamed the Dunbar in 1929, honoring the poet Paul Laurence Dunbar.

In 1930, Lucius W. Lomax, Sr. bought the hotel for $100,000. With a Black owner again, the hotel became "the gem of black Los Angeles" once more. During Somerville's ownership, there was no nightclub. It wasn't until February 1931 that the Dunbar got permission to have a "cabaret in the dining room."

The Dunbar: Heart of the Central Avenue Scene

In the 1930s and 1940s, the Dunbar became known as "the hub of Los Angeles black culture." It was called "the heart of Saturday night Los Angeles." It was like a mix of the fancy Waldorf-Astoria and the famous Cotton Club. The Los Angeles Herald-Examiner described it as "once the most glorious place on 'the Avenue.'" You could dance to Cab Calloway, laugh with Redd Foxx, and maybe get a room near Billie Holiday or Duke Ellington.

The Dunbar hosted many important African Americans visiting Los Angeles. These included Joe Louis, Louis Armstrong, Lena Horne, and Josephine Baker. It was the meeting place for the most important people in Black society. It was the hotel for performers who could entertain in white hotels but were not allowed to sleep in them. In 1940, radio comedian Eddie "Rochester" Anderson used the Dunbar as his base when he was "campaigning" to be the honorary "Mayor of Central Avenue."

The Dunbar also became a place where Black political leaders, thinkers, and writers gathered. People like Langston Hughes, W. E. B. Du Bois, and Thurgood Marshall met there. It was described as "a place where the future of black America was discussed every night." Celes King III, whose family owned the Dunbar, said that doctors, lawyers, and educators had serious talks there. They planned how to improve life for their people.

Future mayor Tom Bradley, who was a young police officer then, was a regular at the Dunbar. He would stop for coffee and conversation. Bradley later remembered walking down the avenue just to see some of the famous stars.

Most of all, the Dunbar is remembered for its role in the Central Avenue jazz scene. The nightclub at the Dunbar was a home and stage for artists like Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Count Basie, Ella Fitzgerald, and Nat King Cole. Even Ray Charles stayed at the Dunbar when he first moved to Los Angeles.

Besides the main nightclub, former heavyweight boxing champion Jack Johnson opened his Showboat nightclub at the Dunbar in the 1930s. Black bands would practice on the mezzanine before playing at other clubs in town.

The hotel was also popular with the white community. Many people from Hollywood spent their Saturday nights at the Dunbar and nearby clubs. Celes King remembered when Bing Crosby once had a check bounce at the hotel. Her father, the owner, kept Crosby's check as a joke between them.

The area around the Dunbar also had other famous jazz clubs, like Club Alabam and the Downbeat. Even local musicians who played at other clubs would gather at the Dunbar. Lee Young, a drummer, recalled that musicians like Charles Mingus and Art Pepper would hang out at the Dunbar between sets. He said you would see movie stars and big show business names there.

Musician Jack Kelson said the sidewalk in front of the Dunbar was the best place to hang out on the coolest street. He called it "the hippest, most intimate, key spot of all the activity." All the night people, business people, dancers, and show business people gathered there. He felt that everyone ended up in front of that hotel.

Another writer said the area around the Dunbar was "a place where people love to congregate and have a good time." The Dunbar became known as "the symbol of L.A.'s black nightlife" in the 1930s. Regular jam sessions and meetings in the lobby made the building almost legendary. Lionel Hampton had great memories of jam sessions on the Dunbar's mezzanine. He remembered that "Everybody that was anybody showed up at the Dunbar."

In his book, Buck Clayton shared his memories of the Dunbar. He said the Dunbar was "jumping" with people trying to see celebrities. Duke Ellington and his band would throw parties with "chicks and champagne everywhere." Clayton remembered when Ellington's band was in the Dunbar restaurant and heard their song It Don't Mean a Thing (If It Ain't Got That Swing) on the jukebox. It was the first time they had heard their own recording since leaving New York. Clayton said the band made so much rhythm, beating on tables and anything else they could find.

The Dunbar was also known for its food. One musician remembered they "had good old southern-fried everything."

The Peace Mission Years

For a short time during the Great Depression, the Dunbar became a hostel for members of the Peace Mission Movement. In 1934, Lucius Lomax sold the hotel to the Peace Mission. The hotel staff left, and the building was changed to house the mission's members. The Peace Mission Movement, led by Father Divine, ran a multi-racial religious community at the Dunbar. They used the dining room for Holy Communion ceremonies. The Dunbar was sold to the Nelson family in the late 1930s. It then went back to being the cultural center for the Black community in Los Angeles.

Changes and New Life for the Dunbar

As racial segregation ended in the 1950s, the need for hotels like the Dunbar changed. Duke Ellington, who used to have a suite at the Dunbar, started staying at the Chateau Marmont in Hollywood. Other famous guests followed. As one writer said, "When the barriers against integration began to crumble in the late 1950s, so did the Dunbar Hotel."

Bernard Johnson bought the Dunbar in 1968, but the hotel kept losing money. Johnson closed the hotel in 1974. While it was closed, comedian Rudy Ray Moore used the hotel for his film Dolemite in 1974. In 1976, the movie A Hero Ain't Nothin' but a Sandwich was also filmed there. Owner Bernard Johnson also opened a museum of Black culture for a while. But from 1974 to 1987, the building was mostly empty and fell into disrepair.

A renovation project started in 1979 but stopped when city funding ran out. By 1987, the Dunbar looked neglected. That year, a plan was announced to turn the Dunbar into affordable housing with a museum of Black culture on the ground floor. The 115 hotel rooms were changed into 72 apartments. The lobby and basement kept their original look and became a museum and cultural center. The project cost $4.2 million, mostly paid for with city funds.

In 1990, the Dunbar re-opened as a 73-unit apartment building for low-income senior citizens and a museum of Black history. Delegates from the NAACP national convention helped celebrate the re-opening in July 1990. Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley attended and praised the efforts to "breathe new life and vigor into this magnificent hotel."

The Dunbar hosted a jazz show in 1991. Music journalist Leonard Feather attended and said it felt like "a visit to a haunted house." When a musician played a Duke Ellington song, Feather imagined Duke himself at a piano on the balcony.

By 1997, the neighborhood around the Dunbar had changed. By 2006, it was mostly Latino and poor. Most nearby shops had signs in Spanish.

Recognized as a Historic Site

In 1974, the Dunbar was named an Historic-Cultural Landmark (number 131) by the city's Cultural Heritage Commission. A plaque called the hotel "an edifice dedicated to the memory and dignity of black achievement." It was also added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1976. The Dunbar was also listed in the Green Book, a guide for African American travelers, from 1940 to 1956.

Major Renovation and Dunbar Village

Around 2005, blues singer Roy Gaines performed at the annual Jazz Festival at the hotel. The hotel had been refurbished and was being used then.

In 2011, Dunbar Village L.P. bought the buildings. The plan was to combine the three existing buildings: the Dunbar Hotel, Somerville I, and Somerville II. They wanted to create one connected, active community that honored South Los Angeles and the historic Dunbar Hotel. This new community is called Dunbar Village.

Along with the physical changes, the community also saw improvements. The new owner put in a modern camera system to help make the buildings safer. This, along with other security steps, helped reduce the number of police visits. The Dunbar went from being a place police visited often to a safe community.

The renovation kept the Dunbar Hotel's historic brick outside, grand entrance, and lobby. The new design provides 41 affordable homes for seniors. It also has a community room, kitchen, media lounge, billiard table, library, and fitness room.

In 2013, Councilwoman Jan Perry and many others attended the re-opening ceremony. Councilwoman Perry said, "Central Avenue and the Dunbar Hotel have long been an important part of our Los Angeles history. It is wonderful to see the Avenue come alive again and know that this historic landmark will be restored for people to enjoy for generations to come." She added that Dunbar Village would keep their shared history alive, create jobs, and offer much-needed affordable housing.

Together, Dunbar Village now has 83 homes. This includes 41 senior homes in the Dunbar Hotel and 42 affordable family homes.

See also

- List of Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monuments in South Los Angeles

- List of Registered Historic Places in Los Angeles

Images for kids

-

Buck Clayton wrote that Duke Ellington threw parties at the Dunbar with "chicks and champagne everywhere."