Economy of the Inca Empire facts for kids

The Inca Empire existed for a short time, from 1438 to 1533. During this period, the Inca civilization created a very successful economic system. This system allowed them to grow lots of food and share products between different communities. Many people think the Inca society had one of the best centrally organized economies in history.

They achieved this by carefully managing people's work and how resources were shared. In Inca society, everyone working together was key to making things and helping everyone become wealthy. People in groups called ayllus worked together to create this wealth. When the Spanish first met the Incas in 1528, they were amazed by how well-off the Incas were. Work was divided by region within each ayllu. For example, farming was done in the best areas for crops. Other ayllus focused on making pottery, building roads, or creating textiles. After each ayllu had what it needed, the government collected any extra goods. These extra goods were then sent to other places where they were needed. In return for their work, people in the Inca Empire received free clothes, food, healthcare, and schooling.

Contents

Ayllus: Family Groups and Work

The Incas built a very successful economy that helped their society grow strong. This success was based on groups called ayllus. An ayllu was made up of families living in the same village or settlement. People often married within their own ayllu, which helped keep society stable.

Each ayllu specialized in making certain goods, depending on where they lived. For example, farming ayllus were located near good land. They grew crops that suited the soil. The government would take their extra crops and send them to other parts of the country where those crops weren't grown. Any extra goods were stored in special buildings near cities or along roads. Other ayllus focused on making pottery, clothes, or jewelry. These skills were passed down from parents to children within the same ayllu. Ayllus produced almost everything people needed for daily life. The government then shared these goods with other ayllus. Because there was plenty of everything, even during bad harvests or conflicts, people stayed loyal to the Sapa Inca (the emperor) and their local leaders.

Land Use in the Inca Empire

People in an ayllu could use land, but they didn't own it. The land belonged to the Inca state. The Kuraka was a local leader, like a chief governor. The Kuraka would divide the land among the ayllu members. How much land a family received depended on the size of their family.

Land was measured in units called tupus. The size of a tupu could change based on how good the land was for farming. A married couple would get one and a half tupus. They would get one more tupu for each son and half a tupu for each daughter. When a son or daughter started their own family, their tupu would be taken away and given to their new family. Each family worked their own land to grow food for themselves.

Working Together: Collective Labor

The Incas regularly counted their male population to see if they needed more workers. People, including teenagers, were asked to work in different jobs in turns. This could be caring for animals, building, or working at home. Farmers gave two-thirds of their crops to the government. This was like a "tax" paid with labor and goods, not money.

In return, the government provided housing, food, and clothing. They even gave out free ceremonial beer as a special treat! The Incas had special open spaces in city centers for people to gather, celebrate, and drink this beer.

Collective labor was organized in three main ways:

- Ayni: This was helping someone in the community who needed it. For example, helping to build a house or assisting someone with a disability.

- Minka: This was a group effort for the good of the whole community or nation. Building farm terraces or cleaning irrigation canals are examples of minka.

- Mita: This was a "tax" paid to the Inca government through labor. Since there was no money, people paid taxes with crops, animals, textiles, and especially their time and work. Mita laborers could be warriors, fishermen, messengers, or road builders. Everyone in an ayllu was expected to do this temporary service in turns. They built temples, palaces, irrigation canals, farm terraces, roads, bridges, and tunnels. They did all this without using wheels! This system was a fair exchange: people worked, and the government provided food, clothes, and medicine. This system made sure the Inca Empire had all the necessary goods to share based on need.

Quipu: The Inca Record System

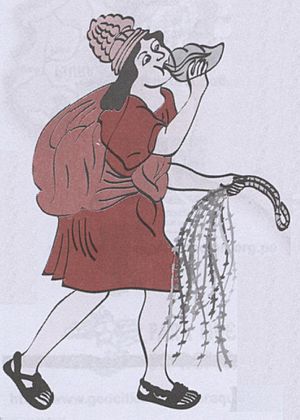

The Incas did not have a written language. But they created a clever way to keep records using knotted strings called "quipu." These strings used complex knots and different colors to represent numbers, often using a base-10 system.

Quipus were used to keep track of stored goods, how many workers were available, and important items like maize (corn), which was used to make ceremonial beer. The "quipu" system managed every part of the empire's economy. People called "Quipucamayocs" were like Inca accountants. They were in charge of keeping and reading the quipu records. The largest quipu found has 1,500 strings! The oldest quipu found is from about 2500 BC, from the Sacred City of Caral Supe.

No Money, No Problem

The Incas did not use money because they didn't need it. Their economy was so well-planned that everyone's basic needs were met. Instead of buying and selling with money, people traded goods directly with each other. This is called bartering. Experts believe the Inca civilization didn't have a special group of traders. However, there was some small trade with people from outside the empire, especially from the Amazon rainforest.

Inca Roads and Bridges

The Incas were amazing builders. They created a huge network of roads and bridges, more complex than many other ancient civilizations. This network was called Qhapaq Ñan. It helped the empire connect and control all its territories, which made it prosperous. Inca engineers improved on roads built by earlier cultures.

In one of the world's toughest landscapes, the Andes mountains, the Incas built over 18,600 miles (30,000 kilometers) of paved roads. Since 1994, these roads and other Inca structures along them have been protected as UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

There were two main roads running north to south: one along the coast and one through the Andes Mountains. Smaller roads connected these two main routes. The coastal road was about 3,000 miles (4,830 km) long. It linked the Gulf of Guayaquil in Ecuador to the Maule River in Chile. The Andean royal path ran through the highlands. It started in Quito, Ecuador, and ended near Tucuman, Argentina, passing through important cities like Cajamarca and Cusco. This Andean Royal Road was over 3,500 miles long, much longer than the longest Roman road.

The Incas did not ride horses or use wheels. Most travel was done on foot. Llamas were used to carry goods from one part of the empire to another. Messengers called chasquis used these roads to deliver messages across the empire. The Incas found ways to build roads through the rugged Andes. They built stone steps on steep slopes, like giant staircases. In desert areas, they built low walls to stop sand from covering the roads.

Building Bridges

Bridges were built all over the Inca Empire. They connected roads that crossed rivers and deep canyons in challenging mountain areas. These bridges were essential for the empire's structure and economy.

The Incas used natural fibers to build impressive suspension bridges, also known as rope bridges. They would tie these fibers together to make long ropes. Then, they braided three of these ropes together to make even stronger, longer ropes. They kept braiding until the ropes were strong enough for the bridge's length and weight. These strong cables were then tied together with tree branches. Timber was placed on top to create a bridge floor that was about four to five feet wide. The finished cable floor was then connected to strong supports on each side of the river or canyon. Ropes were also fixed on the sides to act as handrails. Today, only one Inca suspension bridge remains, near Cusco, in the town of Huarochiri.

Communication Across the Empire

Since the Inca Empire was so large, they needed a way to communicate across it. They created a network of messengers to deliver important messages. These messengers were called Chasquis. They were chosen from the best and fittest young men. They ran long distances every day to relay messages.

The chasquis lived in small groups of four or six in cabins called tambos along the roads. When one chasqui was seen approaching, another would run out to meet him. The new chasqui would run alongside the arriving one, listening carefully to memorize the message. If the message included a quipu, he would take that too. The tired chasqui would then rest in the cabin, while the other ran to the next relay stop. Messages could travel over 250 miles in a single day this way!

If there was an attack or rebellion, an immediate alert was sent using a chain of bonfires. When chasquis saw smoke from a bonfire, they would light their own bonfire. This signal would be seen from the next cabin or tambo. Before the army even knew the reason for the fire, the Sapa Inca would send his army towards the smoke. There, they would usually find a messenger who could explain the emergency. Some tambos were more elaborate than others. They were often used as rest stops for officials or the Sapa Inca as they traveled through the empire.

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |