Caral-Supe civilization facts for kids

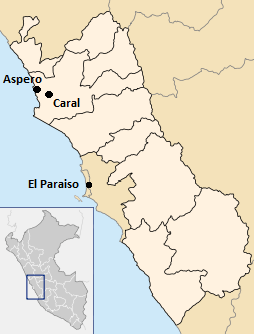

Map of Caral-Supe sites showing their locations in Peru

|

|

| Alternative names | Caral, Norte Chico |

|---|---|

| Geographical range | Lima, Peru |

| Period | Cotton Pre-Ceramic |

| Dates | c. 3,500 BCE – c. 1,800 BCE |

| Type site | Aspero |

| Preceded by | Lauricocha |

| Followed by | Kotosh |

The Caral-Supe civilization, also known as Caral or Norte Chico, was a very old and complex society in what is now the Caral region of north-central coastal Peru. This amazing civilization thrived between about 4000 BC and 2000 BC. The first city, Huaricanga, started around 3500 BC. Large settlements and big building projects became common from 3100 BC until the civilization began to decline around 1800 BC. Since the early 2000s, Caral-Supe has been recognized as the oldest known civilization in the Americas.

This civilization grew along three rivers: the Fortaleza, Pativilca, and Supe. Each river valley had many important sites. Further south, some related sites were found along the Huaura River. The name Caral-Supe comes from the city of Caral in the Supe Valley. Caral is a large and well-studied site of this ancient culture.

Caral-Supe society developed about a thousand years after Sumer in Mesopotamia. It existed at the same time as the Egyptian pyramids were being built. It also came almost two thousand years before the Mesoamerican Olmec civilization.

In archaeology, Caral-Supe is called a pre-ceramic culture from the pre-Columbian Late Archaic period. This means they didn't use ceramics (pottery) and had very little visual art. Their most impressive achievement was their huge buildings. These included large earthwork platform mounds and circular sunken plazas. Archaeologists have found signs of advanced textile technology. They also think the people might have worshipped common symbols of gods. Both of these things were important in later Andean cultures. A complex government was likely needed to manage ancient Caral. Scientists are still studying how this society was organized, especially how food resources affected their leaders.

Archaeologists have known about ancient sites in this area since the 1940s. Early work was done at Aspero on the coast and later at Caral, which is more inland. In the late 1990s, Peruvian archaeologists, led by Ruth Shady, first fully documented this civilization by working at Caral. A 2001 article in Science magazine shared the Caral research. Then, a 2004 article in Nature described fieldwork and radiocarbon dating from a wider area. These articles showed how important Caral-Supe was and made many people interested in it.

Contents

History and Geography of Caral-Supe

The dates found at Caral-Supe sites have pushed back the start of complex societies in Peru by over a thousand years. Before this, the Chavín culture, around 900 BC, was thought to be the first civilization in the area. Sometimes, this is still incorrectly mentioned in books.

The discovery of Caral-Supe also changed where researchers focused. Instead of the highland areas of the Andes (where the Chavín and later Inca had their main centers), attention shifted to the Peruvian coast. Caral is located in a north-central coastal area, about 150 to 200 km north of Lima. It is roughly bordered by the Lurín Valley to the south and the Casma Valley to the north. This region includes four coastal valleys: the Huaura, Supe, Pativilca, and Fortaleza. Most known sites are in the last three, which share a common coastal plain. These three main valleys cover only 1,800 square kilometers, and studies show how densely populated these centers were.

The Peruvian coast seems like an "unlikely" place for a civilization to start from scratch, especially compared to other world centers. It is very dry, caught between two rain shadows. These are caused by the Andes mountains to the east and the Pacific trade winds to the west. However, over 50 rivers carrying snowmelt from the Andes flow through the region. The development of widespread irrigation from these rivers was key to Caral-Supe's rise. All the large buildings at various sites have been found close to irrigation channels.

Radiocarbon dating by Jonathan Haas and his team found that 10 out of 95 samples from the Pativilca and Fortaleza areas dated from before 3500 BC. The oldest, from 9210 BC, shows "limited indication" of human settlement during the early Archaic era. Two dates from 3700 BC are linked to communal buildings, but these might be unusual. It is from 3200 BC onwards that large human settlements and community building projects clearly appeared. Experts suggest that the Caral-Supe period began "sometime before 3200 BC, and possibly before 3500 BC." The earliest date definitely linked to a city is 3500 BC, at Huaricanga, in the Fortaleza area.

Haas's early dates suggest that coastal and inland sites developed at the same time. But from 2500 to 2000 BC, during the time of greatest growth, the population and development clearly moved towards the inland sites. All major growth happened at large inland sites like Caral. However, these sites still relied on fish and shellfish from the coast. The peak dates match Shady's findings at Caral, which show people lived there from 2627 BC to 2020 BC. However, whether coastal and inland sites developed together is still debated.

How Far Did Caral-Supe's Influence Reach?

By around 2200 BC, the Caral-Supe civilization's influence spread widely along the coast. To the south, it reached as far as the Chillon valley and the site of El Paraiso. To the north, it spread to the Santa River valley.

Around 1800 BC, the Caral-Supe civilization started to decline. More powerful centers began to appear to the south and north along the coast, and to the east in the Andes mountains. The success of their irrigation-based farming might have played a part in its decline. Professor Winifred Creamer notes that "when this civilization is in decline, we begin to find extensive canals farther north." This suggests people were moving to more fertile land and taking their irrigation knowledge with them. It would be a thousand years before the next great Peruvian culture, the Chavín, rose to power.

Geographical Connections

Archaeologists have noticed cultural links between Caral-Supe and the highland areas. Ruth Shady points out connections with the Kotosh Religious Tradition:

Many building features found in the Supe settlements are similar to those in the Kotosh Religious Tradition. These include underground circular courts, stepped pyramids, and layered platforms. Also, materials found at Aspero and other valley sites like Caral, Chupacigarro, Lurihuasi, and Miraya show these links. Specific features include rooms with benches and hearths with underground air ducts, wall niches, special beads, and musical flutes.

Coastal and Inland Food Sources

Research into Caral-Supe is ongoing, with many questions still unanswered. There's a debate about two related topics: how much the Caral-Supe civilization relied on food from the sea, and what this means for the relationship between coastal and inland sites.

What Did They Eat?

We have a good idea of what the Caral-Supe people ate. At Caral, Shady found evidence of domesticated plants like squash, beans, lúcuma, guava, pacay (Inga feuilleei), and sweet potato. Haas and his team found the same foods further north, adding avocado and achira. In 2013, strong evidence for maize (corn) was also found by Haas and his team.

Seafood was also a very important part of their diet at both coastal and inland sites. Shady notes that "animal remains are almost exclusively marine" at Caral. These include clams, mussels, and large amounts of anchovies and sardines. It's clear that anchovy fish reached inland areas. However, Haas suggests that "shellfish, sea mammals, and seaweed do not appear to have been significant parts of the diet in the inland, non-maritime sites."

The Idea of a Maritime Foundation

The role of seafood in the Caral-Supe diet has caused much discussion. Much early research was done at Aspero on the coast. This was before the full size and connections of the civilization's sites were understood. In a 1973 paper, Michael E. Moseley argued that a seafood-based economy was the foundation of this society. He believed this allowed it to flourish so early. This idea was later called the "maritime foundation of Andean civilization" (MFAC). He confirmed that there was no pottery at Aspero. He also figured out that mounds on the site were the remains of artificial platform mounds.

This idea of a maritime foundation went against the common belief that civilizations rise because of intensive farming, especially of grains. Producing extra food from farming had long been seen as essential for growing populations and complex societies. Moseley's ideas were debated, but they were still considered possible as late as 2005.

Along with the maritime food idea, it was thought that coastal sites were more important than other centers. This idea changed when the huge size of Caral, an inland site, was realized. A 2001 Science article, following Shady's 1997 paper on Caral, stressed the importance of farming. It also suggested that Caral was the oldest urban center in Peru (and all the Americas). It disagreed with the idea that civilization started on the coast and then moved inland. One archaeologist was quoted saying that "rather than coastal beginnings for monumental inland sites, what we have now are coastal satellite villages to monumental inland sites."

These claims were quickly challenged by other researchers. They agreed that farming was important for industry and to add to the diet. But they still believed in "the formative role of marine resources in early Andean civilization." Scholars now agree that the inland sites had much larger populations. There were "so many more people along the four rivers than on the shore that they had to have been dominant."

The question that remains is which area developed first and set the pattern for later growth. Haas disagrees with the idea that maritime development on the coast came first. He points to his dating, which shows development happening at the same time. Moseley still believes that coastal Aspero is the oldest site. He thinks its seafood-based living was the foundation for the civilization.

Cotton and Food Sources

The use of cotton (a plant called Gossypium barbadense) played a key economic role in the relationship between the inland and coastal settlements in Peru. However, experts still disagree on the exact timeline of these developments.

Even though it's not edible, cotton was the most important product grown with irrigation in the Caral-Supe culture. It was vital for making fishing nets (which provided seafood) and for textiles and clothing technology. Haas notes that "control over cotton allows a ruling elite to provide the benefit of cloth for clothing, bags, wraps, and adornment." He points out a mutual dependency: "The prehistoric residents of the Norte Chico needed the fish resources for their protein and the fishermen needed the cotton to make the nets to catch the fish." So, identifying cotton as a vital inland resource doesn't by itself solve the question of whether inland centers led the way for coastal ones, or vice versa. Moseley argues that successful coastal centers would have moved inland to find cotton.

In a 2018 publication, David G. Beresford-Jones and his co-authors supported Moseley’s (1975) Maritime Foundations of Andean Civilization (MFAC) idea.

The authors updated and refined Moseley’s MFAC idea. They now believe it "emerges more persuasive than ever." They suggest that the potential for growing more food, which cotton farming allowed, was key to causing revolutionary social change and complex society. Before cotton, people used bast fibers from wild Asclepias for fiber production, which was much less efficient.

Beresford-Jones and others also provided more support for their ideas in 2021.

How Research Developed

It was a Swiss archaeologist named fr:Frédéric Engel who first used the term "Cotton Preceramic Stage" in 1957. He used it to describe unusual coastal sites like Norte Chico that had cotton but no pottery and were very old. This stage was thought to last about 1200 years, from 3000 to 1800 BC.

The development of Caral-Supe is especially notable because it seemed to lack a main staple food crop. However, recent studies increasingly challenge this idea. They point to maize (corn) as a key part of the diet for this and later pre-Columbian civilizations. Moseley found a small number of maize cobs in 1973 at Aspero. However, he has since called the find "problematic." Still, more and more evidence shows the importance of maize during this period:

Archaeological tests at several sites in the Norte Chico region show a lot of information about growing, processing, and eating maize. New data from ancient human waste, pollen records, and stone tool residues, along with 126 radiocarbon dates, prove that maize was widely grown, processed a lot, and was a main part of the diet from 3000 to 1800 BC.

For Beresford-Jones, his new research on two nearby ancient coastal settlements, La Yerba, was very important. These sites are on the east bank of the Ica River, not far from the town of Ica in southern Peru. The older settlement was La Yerba II (around 5570-4670 BC). When people lived there, La Yerba II was close to the ancient shoreline. This was not a place where people lived all the time.

La Yerba III, a slightly later site, was a permanently occupied settlement. It shows a population that was much larger than before. Many Obsidian stone flakes were found at La Yerba III, unlike the earlier site. This suggests more interaction with the highlands, where obsidian was found.

The people of La Yerba III already practiced some farming in floodplains. They grew gourds, Phaseolus beans, and Canavalia beans. Producing plant fibers was very important for their fishing economy. So, they were "ready for a Cotton Revolution."

Social Organization of Caral-Supe

How Was Their Government Structured?

It's hard to know exactly how much power was held by a central authority. However, the way buildings were constructed suggests that, at least in some places and times, an elite group had significant power. While some large buildings were built bit by bit, others, like the two main platform mounds at Caral, seem to have been built in one or two intense periods. As further proof of central control, Haas points to large stone warehouses found at Upaca. These warehouses suggest that leaders could control important resources like cotton.

Haas suggests that the way labor was organized, as shown by archaeological evidence, points to a unique way human government first appeared. He believes it's one of two places where government was "invented" (the other being Sumer, or three if Mesoamerica is included). In other cases, the idea of government would have been borrowed. Other archaeologists have said these claims are too strong.

When looking at how government might have formed, Haas suggests three main sources of power for early complex societies:

- Economic power,

- Ideological (belief-based) power, and

- Physical power.

He finds the first two present in ancient Caral-Supe.

Economic Power

Economic power would have come from controlling cotton, edible plants, and related trade. Power would have been centered in the inland sites. Haas cautiously suggests that this economic power might have spread widely. There are only two confirmed coastal sites in Caral-Supe (Aspero and Bandurria) and possibly two more. But cotton fishing nets and domesticated plants have been found all along the Peruvian coast. It's possible that the main inland centers of Caral-Supe were at the heart of a large regional trade network based on these resources.

Citing Shady, a 2005 article in Discover magazine suggests a rich and varied trade life. It states that "[Caral] exported its own products and those of Aspero to distant communities in exchange for exotic imports: Spondylus shells from the coast of Ecuador, rich dyes from the Andean highlands..." Other reports on Shady's work indicate Caral traded with communities in the jungle further inland and possibly with people from the mountains.

Ideological Power

Haas believes that the leaders' ideological power came from their apparent connection to gods and the supernatural. Evidence about Caral-Supe religion is limited. In 2003, an image of the Staff God, a fierce-looking figure with a hood and fangs, was found on a gourd dating to 2250 BC. The Staff God is a major god in later Andean cultures. Winifred Creamer suggests this find points to the worship of common symbols of gods. Like much other research at Caral-Supe, the meaning of this find has been debated by other researchers.

Experts suggest that building and maintaining the architecture at Caral-Supe might have been a spiritual or religious experience. It could have been a process of community celebration and ceremony. Shady has called Caral "the sacred city" (la ciudad sagrada). She reports that the social, economic, and political focus was on the temples. These temples were regularly rebuilt, with large burnt offerings made during the rebuilding.

Physical Power (or Lack Thereof)

Haas notes that there is no sign of physical power, like defensive buildings, at Caral-Supe. There is no evidence of warfare "of any kind or at any level during the Preceramic Period." No bodies, burned buildings, or other signs of violence have been found. The settlement patterns show no defensive features. The fact that a complex government developed without warfare is very different from archaeological theories. These theories often suggest that humans move from family-based groups to larger "states" for mutual defense of often scarce resources. In Caral-Supe, an important resource was present: arable land in general, and the cotton crop specifically. But it seems the culture's move to greater complexity was not driven by the need for defense or war.

Sites and Architecture

Caral-Supe sites are known for having many large sites with huge buildings. Haas argues that the density of sites in such a small area is unique for a civilization just starting out. During the third millennium BC, Caral-Supe might have been the most densely populated area in the world (perhaps except for Northern China). The Supe, Pativilca, Fortaleza, and Huaura River valleys of Caral-Supe each have several related sites.

Evidence from the important work in 1973 at Aspero, at the mouth of the Supe Valley, suggested a site of about 13 hectares (32 acres). Surveys of the midden (ancient trash heaps) showed extensive prehistoric building activity. Small-scale terracing was noted, along with more advanced platform mound masonry (stone work). As many as eleven artificial mounds were thought to exist at the site. Moseley calls these "Corporate Labor Platforms." This is because their size, layout, and building materials would have required an organized workforce.

Surveys of the northern rivers found sites between 10 and 100 hectares (25 to 250 acres). Between one and seven large platform mounds—rectangular, terraced pyramids—were discovered. They ranged in size from 3,000 cubic meters to over 100,000 cubic meters. Shady notes that the central area of Caral, with its monumental architecture, covers just over 65 hectares (160 acres). Also, six platform mounds, many smaller mounds, two sunken circular plazas, and various residential buildings were found at this site.

The huge buildings were constructed with quarried stone and river cobbles. Laborers would have carried the materials to the sites by hand using reed "shicra-bags." Some of these bags have been preserved. Roger Atwood of Archaeology magazine describes the process:

Armies of workers would gather a long, strong grass called shicra from the highlands above the city. They would tie the grass into loosely woven bags, fill the bags with boulders, and then pack the trenches behind each retaining wall of the step pyramids with these stone-filled bags.

In this way, the people of Norte Chico achieved impressive architectural success. The largest platform mound at Caral, the Piramide Mayor, measures 160 by 150 meters (520 by 490 feet) and rises 18 meters (59 feet) high. The BBC suggests workers would have been "paid or forced" to work on such large projects. Dried anchovies might have even been used as a form of payment. Experts point to "ideology, charisma, and skilfully timed reinforcement" from leaders as motivators.

Technology and Unique Features

When compared to how civilizations developed in Europe and Asia, Caral-Supe's differences are striking. In Caral-Supe, there was a complete lack of ceramics (pottery) throughout the entire period. Crops were cooked by roasting. The absence of pottery also meant there was almost no art that archaeologists could find. One expert noted: "In the Norte Chico we see almost no visual art. No sculpture, no carving or bas-relief, almost no painting or drawing—the interiors are completely bare. What we do see are these huge mounds—and textiles."

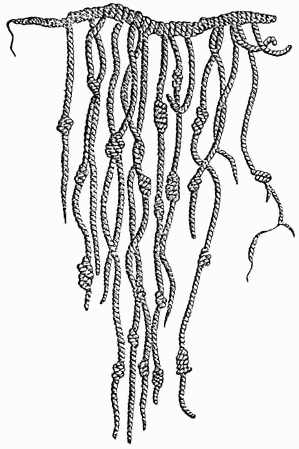

While the lack of pottery seems unusual, the presence of textiles is very interesting. Quipu (or khipu), which are string-based recording devices, have been found at Caral. This suggests a writing, or proto-writing, system existed in Caral-Supe. (This discovery was reported in Science in 2005, but has not been officially published by Shady.) The exact use of quipu in this and later Andean cultures has been widely debated. At first, it was thought to be a simple way to remember numbers, like counting items bought and sold. However, evidence has emerged that quipu might also have recorded word-based information, similar to how writing works. Research has focused on the much larger number of quipu from Inca times. The Caral-Supe discovery remains unique and has not yet been fully understood.

Other finds at Caral-Supe have been very telling. While visual arts seem to be missing, the people may have played instrumental music. Thirty-two flutes, made from pelican bone, have been discovered.

The oldest known image of the Staff God was found in 2003 on broken gourd pieces in a burial site in the Pativilca River valley. The gourd was carbon dated to 2250 BCE. While still incomplete, such archaeological evidence matches patterns found in later Andean civilizations. This might mean that Caral-Supe served as a model for them. Along with specific finds, experts highlight:

"the importance of trade over a wide area, the tendency for community, festive public work projects, [and] the high value placed on textiles and textile technology" within Norte Chico as patterns that would appear again later in the Peruvian cradle of civilization.

Academic Debates

The huge importance of the Caral-Supe discovery has led to disagreements among researchers. This "monumental feud," as described by Archaeology, has included "public insults" and complaints. The main author of the important paper from April 2001 was a Peruvian, Ruth Shady. Her co-authors were Jonathan Haas and Winifred Creamer, a married team from the United States. Haas reportedly suggested they co-author, hoping that having U.S. researchers involved would help get funds for carbon dating and future research. Later, Shady accused the couple of not giving her enough credit. She suggested they received credit for her research, which had started in 1994.

The main issues are who gets credit for discovering the civilization, naming it, and developing the ideas to explain it. In 1997, Shady described a civilization located on the Supe River, with Caral as its center. However, she suggested the society had a larger geographical base.

In 2004, Haas and his team wrote that "Our recent work in the neighboring Pativilca and Fortaleza has revealed that Caral and Aspero were but two of a much larger number of major Late Archaic sites in the Norte Chico." They only mentioned Shady in footnotes. This type of credit is what angered Shady and her supporters. Shady's position has been made harder by a lack of funding for archaeological research in Peru. Also, North American researchers often have an advantage in getting media attention in these kinds of disputes.

Haas and Creamer were cleared of the plagiarism charge by their institutions. However, the science advisory council of the Chicago Field Museum of Natural History criticized Haas. They said his press releases and web pages gave too little credit to Shady and made the American couple's role as discoverers seem bigger than it was.

|

See also

In Spanish: Civilización caral para niños

In Spanish: Civilización caral para niños