Edward Bok facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Edward Bok

|

|

|---|---|

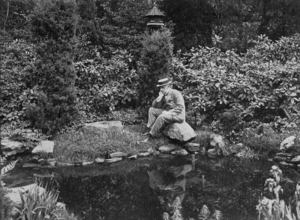

Bok c. 1918

|

|

| Born | Eduard Willem Gerard Cesar Hidde Bok October 9, 1863 Den Helder, Netherlands |

| Died | January 9, 1930 (aged 66) Lake Wales, Florida, US |

| Occupation |

|

| Nationality | American |

| Notable works | Successward, The Young Man in Business, The Young Man & The Church, The Americanization of Edward Bok |

| Notable awards | Pulitzer Prize |

| Spouse | Mary Louise Curtis |

Edward William Bok (born Eduard Willem Gerard Cesar Hidde Bok) (October 9, 1863 – January 9, 1930) was a famous editor and author from the Netherlands who later became an American citizen. He won a Pulitzer Prize for his writing. For 30 years (1889–1919), he was the editor of the Ladies' Home Journal, a very popular magazine. He also helped people build better homes by sharing building plans and created the beautiful Bok Tower Gardens in central Florida.

Contents

Edward Bok's Early Life and Career

Edward Bok was born in Den Helder, Netherlands, into a wealthy family. When he was six, his family lost most of their money because of bad investments. They then moved to Brooklyn, New York.

To help his family, Edward washed bakery windows after school. He also collected bits of coal from the street. By his early teens, he had to leave school to work full-time. In 1876, his first job was as an office boy at the Western Union Telegraph company.

In 1882, Bok started working as a stenographer (someone who takes notes quickly) for Henry Holt and Company. He also took classes in the evenings. In 1884, he became an advertising manager for Charles Scribner's Sons.

From 1884 to 1887, Bok edited The Brooklyn Magazine. In 1886, he started the Bok Syndicate Press. This company shared articles with 137 newspapers across the country.

Leading the Ladies' Home Journal

In 1889, Edward Bok moved to Philadelphia. He became the editor of the Ladies' Home Journal. The magazine's founder, Louisa Knapp Curtis, stepped down. The Journal was a popular magazine read by many people across the nation. It was published by Cyrus Curtis, who owned many newspapers and magazines.

In 1896, Bok married Mary Louise Curtis, who was Louisa and Cyrus Curtis's daughter. Mary loved music, cultural activities, and helping others (called philanthropy). She was also active in social groups.

Under Bok's leadership, the Journal became the first magazine in the world to have one million subscribers. It became very important to its readers. The magazine shared helpful and new ideas in its articles. It also focused on important social issues of the time.

Edward Bok's autobiography, The Americanization of Edward Bok, came out in 1920. It won a Pulitzer Prize. A famous writer, H. L. Mencken, reviewed the book. He noted that Bok cared a lot about art and beauty. Mencken said Bok wanted to make American homes and towns more beautiful. He started many campaigns in the Journal to improve home design, furniture, clothing, and advertising. Most of these campaigns worked.

The Journal was also the first magazine to refuse advertisements for patent medicine (medicines that often made false claims). In 1919, Bok retired from publishing.

Edward Bok's Later Projects

In 1923, Bok suggested the American Peace Award. He also created other awards, including a $100,000 prize in 1923. This prize was for the best plan for the U.S. to help achieve world peace.

In 1924, Mary Louise Bok started the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia. She named it after her father, Cyrus Curtis. In 1927, the Boks began building Bok Tower Gardens. It was near their winter home in Lake Wales, Florida. On February 1, 1929, the U.S. president, Calvin Coolidge, officially opened the gardens. Bok Tower is sometimes called a sanctuary. It is listed as a National Historic Landmark.

Edward Bok died on January 9, 1930, from a heart attack in Lake Wales. He passed away while looking at his beloved Singing Tower. He was buried at the base of the tower. His grandsons include educator Derek Bok and folk singer Gordon Bok.

Edward Bok and American Homes

In 1895, Bok started publishing house plans in Ladies' Home Journal. These plans were for homes that middle-class American families could afford, costing $1,500 to $5,000. People could buy full building plans with prices for their region for $5.

Later, Bok and the Journal strongly promoted the "bungalow" style of house. This style came from India. Plans for these houses cost as little as a dollar. These small, one-and-a-half-story homes, some as small as 800 square feet, quickly became very popular across the country.

Some architects complained that Bok was taking their jobs by selling plans widely. Architect Stanford White at first disagreed with Bok. But White later changed his mind, saying that Edward Bok had improved American home architecture more than anyone else in his time.

Bok also suggested using the term living room for the room often called a parlor or drawing room. This room was usually only used on Sundays or for special events. Bok thought it was silly to have an expensive room that was rarely used. He wanted families to use this room every day. He believed it was foolish to have a room that "draws attention to too much money and no taste."

Overall, Bok wanted to keep his traditional idea of the perfect American home. He believed the wife should be a homemaker and raise children. He also thought children should grow up in a healthy, natural place. Because of this, he promoted living in the suburbs as the best way to have a balanced family life.

Theodore Roosevelt once said about Bok: "He is the only man I ever heard of who changed, for the better, the architecture of an entire nation."

Edward Bok's Views on Women's Roles

At the Ladies' Home Journal, Edward Bok wrote more than twenty articles against women's suffrage (the right for women to vote). He believed women were not ready to vote. His views went against his idea of women being homemakers living a simple life. Since the Journal reached many middle-class women, Bok became an important supporter of the movement against women's voting rights.

Bok also did not support women working outside the home. He disagreed with some parts of the women's clubs and higher education for women. He wrote that feminism would lead to problems for women, like divorce or poor health. Bok asked former presidents Grover Cleveland and Theodore Roosevelt to write articles against women's rights. (Though Roosevelt later changed his mind and supported women's suffrage.) Bok saw women who supported voting rights as disloyal to their gender. He said, "there is no greater enemy of woman than woman herself."

However, the magazine also supported good causes. These included protecting nature, public health, clean living, and improving education.

Some women's clubs tried to boycott the Journal because of its criticism. Bok threatened to take legal action. But he later reached an agreement with the General Federation of Women’s Clubs. The magazine started a new section with content provided by the Federation.

Awards and Honors for Edward Bok

Edward Bok's 1920 autobiography, The Americanization of Edward Bok: The Autobiography of a Dutch Boy Fifty Years After, won the Gold Medal from the Academy of Political and Social Science. It also won the 1921 Pulitzer Prize for Biography or Autobiography.

During World War II, a Liberty ship called SS Edward W. Bok was named in his honor.

The Edward W. Bok Technical High School in Philadelphia, which opened in 1938 and closed in 2013, was also named after him.

Edward Bok's Books

- Successward (1895)

- The Young Man in Business (1895)

- The Young Man & The Church (1896)

- Her Brother's Letters (1906)

- Why I Believe in Poverty (1915)

- The Americanization of Edward Bok (1920)

- A Dutch Boy Fifty Years After, edited by John Louis Haney (1921)

- Two Persons (1922)

- A Man from Maine (1923)

- Twice Thirty (1925)

- Dollars Only (1926)

- You: A Personal Message (1926)

- America Give Me a Chance (1926)

- Perhaps I Am (1928)

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |