Electromagnet facts for kids

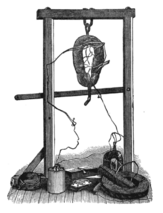

Homemade electromagnet with 9V battery

|

|

| Type | Magnet |

|---|---|

| Working principle | Oersted's law |

| Electronic symbol | |

|

|

An electromagnet is a special kind of magnet that gets its magnetic power from an electric current. Imagine wrapping a wire, usually made of copper, into a tight coil. When electricity flows through this wire, it creates a magnetic field right in the middle of the coil. The amazing thing about electromagnets is that you can turn their magnetism on and off! When you switch off the electricity, the magnetic field disappears.

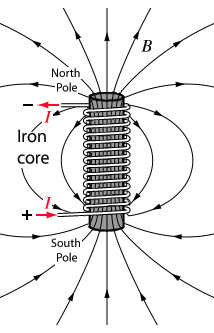

Often, this wire coil is wrapped around a special piece of material called a magnetic core. This core is usually made of iron or similar materials. The core helps to gather and focus the magnetic field, making the electromagnet much more powerful.

The biggest advantage of an electromagnet compared to a regular permanent magnet is that you can easily control its strength. By changing how much electricity flows through the wire, you can make the magnetic field stronger or weaker very quickly. However, unlike a permanent magnet that needs no power, an electromagnet needs a constant supply of electricity to stay magnetic.

Electromagnets are super useful! They are found in many everyday devices. Think about motors that make things move, generators that create electricity, loudspeakers that make sound, and even hard disks that store computer data. Big electromagnets are also used in factories to lift and move heavy metal objects like scrap iron.

Contents

A Look Back: How Electromagnets Were Discovered

The story of electromagnets began in 1820. A Danish scientist named Hans Christian Ørsted made an exciting discovery: he found that electric currents could create magnetic fields. Later that same year, a French scientist, André-Marie Ampère, showed that you could magnetize iron by putting it inside an electrically powered coil of wire, called a solenoid.

The very first electromagnet was invented in 1824 by a British scientist named William Sturgeon. He took a horseshoe-shaped piece of iron and wrapped about 18 turns of bare copper wire around it. Since insulated wire didn't exist yet, he varnished the iron to keep the wire from touching it directly. When he sent electricity through the coil, the iron became magnetic and could attract other metal pieces. When he turned off the electricity, it lost its magnetism. Sturgeon showed how powerful his invention was: even though his electromagnet weighed only about 200 grams, it could lift roughly 4 kilograms!

Starting in 1830, an American scientist, Joseph Henry, made electromagnets much better and more popular. He used wire that was insulated with silk thread. This allowed him to wrap many layers of wire around the iron cores. Henry created incredibly strong magnets, some that could lift over 900 kilograms! These powerful electromagnets were first widely used in telegraph sounders, which were early communication devices.

Where We Use Electromagnets

Electromagnets are everywhere! They are key parts of many electrical and mechanical devices. Here are some examples:

- Motors and Generators: They help create motion in motors and produce electricity in generators.

- Relays: These are electrical switches that use a small current to control a larger one.

- Bells and Buzzers: The ringing sound of an electric bell often comes from an electromagnet.

- Speakers and Headphones: Electromagnets make the tiny parts vibrate to produce sound in loudspeakers and headphones.

- Data Storage: Devices like tape recorders, VCRs, and hard disks use electromagnets to record and read information.

- Medical Imaging: MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) machines use very powerful electromagnets to create detailed images of the inside of your body.

- Scientific Tools: Instruments like mass spectrometers and particle accelerators rely on electromagnets to guide tiny particles.

- Lifting and Sorting: Large industrial electromagnets can lift heavy scrap metal. They are also used to separate magnetic materials from non-magnetic ones.

- Maglev Trains: Some advanced trains use magnetic levitation to float above the tracks, reducing friction and allowing for very high speeds.

How Electromagnets Work: The Basics

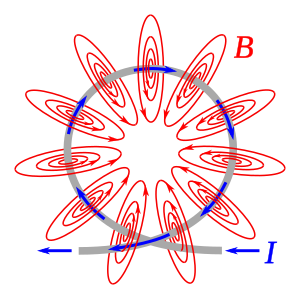

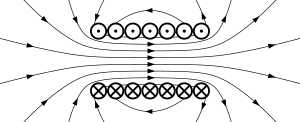

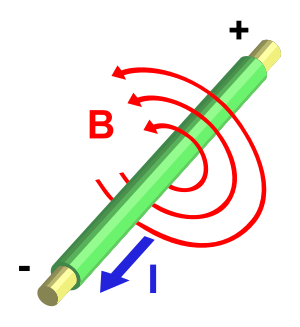

The fundamental idea behind an electromagnet is simple: an electric current moving through a wire creates a magnetic field around that wire. To make this field stronger and more useful, the wire is wound into a coil with many turns. All the magnetic fields from each turn of wire combine in the center of the coil, creating a powerful magnetic field there. A coil shaped like a straight tube is called a solenoid.

You can figure out the direction of the magnetic field inside a coil using the right-hand rule. Imagine curling the fingers of your right hand around the coil in the direction the electricity is flowing. Your thumb will then point in the direction of the magnetic field inside the coil. This direction is also known as the north pole of the electromagnet.

Making Magnets Stronger with a Core

You can make electromagnets much, much stronger by placing a magnetic core inside the coil. This core is usually made of a "soft" ferromagnetic material, like iron. A core can boost the magnetic field to thousands of times the strength of the coil alone! This happens because these materials have a high magnetic permeability, meaning they are very good at letting magnetic fields pass through them.

The material of the magnetic core is made up of tiny regions called magnetic domains. Think of these domains as tiny, individual magnets. Before you turn on the electromagnet, these tiny magnets point in random directions, so their magnetic effects cancel each other out. The core doesn't act like a big magnet.

But when electricity flows through the wire coil, its magnetic field reaches into the core. This field makes the tiny magnetic domains inside the core line up in the same direction as the field. When they all line up, their tiny magnetic fields add together, creating a much larger and stronger magnetic field that extends around the electromagnet. The core essentially concentrates the magnetic field, making it more powerful.

The more current you send through the wire coil, the more the tiny domains align, and the stronger the magnetic field becomes. However, there's a limit. Once all the domains are lined up, sending more current won't make the magnet much stronger. This point is called saturation. For most iron cores, the maximum magnetic field strength is around 1.6 to 2 teslas. This is why super-strong electromagnets, like those using superconductors, can't use iron cores.

When you turn off the electricity, most of the domains in the core lose their alignment and return to a random state, and the magnetic field disappears. However, some alignment might remain, leaving the core slightly magnetized. This leftover magnetism is called remanent magnetism.

Understanding Electromagnet Challenges

Electromagnets are amazing, but designing them involves dealing with a few challenges.

Keeping Cool: Heat in Electromagnets

When electricity flows through the wires of an electromagnet, the wires have some resistance. This resistance causes some of the electrical energy to turn into heat. This is why wires can get warm! In very large and powerful electromagnets, so much heat is produced that special cooling systems, often using water, are needed to prevent the wires from overheating.

To reduce heat, designers can use thicker wires (which have less resistance) or wrap more turns of wire around the core. Both methods help to lower the amount of heat produced for a given magnetic strength.

Protecting Circuits: Voltage Spikes

An electromagnet acts like an inductor, meaning it resists sudden changes in the electric current flowing through it. If you suddenly turn off an electromagnet, the energy stored in its magnetic field has to go somewhere. This can cause a very large, sudden surge of voltage across the wires, called a voltage spike.

These voltage spikes can create sparks at the switch that turns the electromagnet on or off, potentially damaging the switch. To prevent this, a special electronic component called a diode is often used. The diode provides a safe path for the electricity to flow back through the coil until all the stored energy is used up as heat, protecting the switch and other parts of the circuit.

Strong Forces on Wires

In powerful electromagnets, the magnetic field itself pushes on the wires that create it. This is due to something called the Lorentz force. This force tries to push the wires outwards in all directions, and also pulls adjacent turns of wire closer together.

These forces can be very strong, especially in large magnets. Designers must make sure the wires are held very firmly in place. Otherwise, the constant pushing and pulling when the magnet is turned on and off could cause the wires to break over time.

Energy Loss in AC Electromagnets

Some electromagnets use alternating current (AC), where the electricity constantly changes direction. This means the magnetic field is also constantly changing. This changing field causes two main types of energy loss in the core, which turn into heat:

- Eddy Currents: A changing magnetic field can create swirling electric currents, called eddy currents, inside nearby conductors, like the iron core itself. These currents generate heat and waste energy. To reduce them, AC electromagnet cores are often made from thin sheets of steel, called laminations, stacked together with insulating layers in between. This forces the eddy currents to flow in much smaller loops, greatly reducing the heat.

- Hysteresis Losses: When the magnetic field keeps reversing direction, the tiny magnetic domains in the core have to keep flipping their alignment. This takes energy and creates heat. To minimize this, cores for AC electromagnets are made from "soft" magnetic materials that can change their magnetization easily.

Super Strong Electromagnets

Sometimes, scientists and engineers need magnetic fields much stronger than what a regular iron-core electromagnet can produce.

Superconducting Magnets

To get magnetic fields stronger than the 1.6 to 2 Tesla limit of iron cores, superconducting electromagnets are used. These magnets use special wires made of superconducting materials. When cooled to very low temperatures, often with liquid helium, these wires can carry electricity with absolutely no electrical resistance. This means huge currents can flow, creating incredibly intense magnetic fields.

Superconducting magnets are limited by how strong a field their wire material can handle before it stops being superconducting. As of 2017, designs were limited to 10–20 Tesla, with a record of 32 Tesla for a purely superconducting magnet. While they need expensive cooling equipment, they save a lot of energy during operation because no power is lost as heat in the wires. They are essential in particle accelerators and MRI machines.

Bitter Magnets

When even stronger fields are needed, beyond what superconducting magnets can do alone, scientists use air-core electromagnets called Bitter electromagnets. These were invented by Francis Bitter in 1933. Instead of traditional wire coils, a Bitter magnet uses stacks of conducting disks arranged in a spiral path. Electricity flows through these disks, creating a very strong magnetic field in the center.

This design is very strong mechanically, allowing it to withstand the extreme Lorentz forces that try to push the magnet apart. The disks also have holes for cooling water to flow through, carrying away the massive amount of heat produced by the high currents. As of 2017, the strongest continuous field made purely with a resistive magnet was 41.5 Tesla. The strongest continuous magnetic field overall, 45 Tesla, was achieved in June 2000 using a hybrid system that combined a Bitter magnet inside a superconducting magnet.

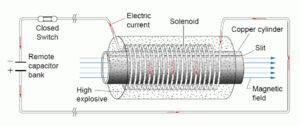

Extreme Magnets: Explosive Power

The most powerful magnetic fields ever created by humans are made using a method called explosively pumped flux compression generators. These devices use explosives to quickly squeeze a magnetic field inside an electromagnet. This compression can boost the magnetic field to values around 1,000 Tesla, but only for a tiny fraction of a second (a few microseconds).

While the name sounds dramatic, these devices are carefully designed. They use special shaped charges to direct the explosive force, minimizing damage to the surrounding area. These "destructive pulsed electromagnets" are used in physics and materials science research to study how materials behave in extremely high magnetic fields.

See also

In Spanish: Electroimán para niños

In Spanish: Electroimán para niños

- Dipole magnet – the most basic form of magnet

- Electromagnetism

- Electropermanent magnet – a magnetically hard electromagnet arrangement

- Field coil

- Magnetic bearing

- Pulsed field magnet

- Quadrupole magnet – a combination of magnets and electromagnets used mainly to affect the motion of charged particles