Empire Ranch facts for kids

Quick facts for kids |

|

|

Empire Ranch

|

|

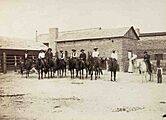

The Empire Ranch headquarters.

|

|

| Location | Las Cienegas, Arizona, United States |

|---|---|

| Built | c.1871 |

| NRHP reference No. | 75000354 |

| Added to NRHP | 1976 |

The Empire Ranch is a historic cattle ranch located in southeastern Pima County, Arizona. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1976 because of its important history.

Back in its busiest days, the Empire Ranch was one of the biggest ranches in Arizona. It covered a huge area of over 180 square miles. Its owner, Walter L. Vail, played a big part in starting the cattle industry in southern Arizona. Today, the ranch is owned by the Bureau of Land Management. A private company still uses it for grazing cattle.

Contents

History of Empire Ranch

Starting the Ranch

The Empire Ranch is found on the eastern side of the Santa Rita Mountains. It's in the Cienega Valley, about 52 miles southeast of Tucson. The ranch sits near a small dip in the land called Empire Gulch. A tiny stream flows through it, surrounded by cottonwood trees. The nearby fields are full of tall grasses.

A businessman from Tucson, Edward Nye Fish, first settled this spot in 1871. We're not sure if he built the first four-room adobe house and corral. They might have been there before he arrived.

In 1876, Walter Vail and his business partner, Herbert R. Hislop, bought the ranch. They purchased it from Edward Fish and his partner, Simon Silverberg. The sale included 612 head of cattle. Vail and Hislop immediately started buying more land. They also improved the ranch's buildings and fences. At its peak, the Empire Ranch controlled 180 square miles of land. This land stretched between several mountain ranges.

When Walter's wife, Margaret, moved to the ranch in 1881, many improvements were made. Walter had already added a kitchen, pantry, and office. These were mostly for the cowboys working there. After Margaret arrived, Walter built an eight-room addition for her. This included bedrooms, a living room, and a dining area. The new part of the house had high ceilings and three fireplaces. It even had a fancy bay window. The Empire Ranch house became a very impressive home in southern Arizona. Margaret loved living there, which was unusual for ranch families at the time. Over the years, more rooms were added. Today, the house has 22 rooms and is carefully preserved.

The exact reason for the name "Empire Ranch" isn't fully clear. Walter's brother, Edward, said Walter named it. He claimed Walter wanted to "make an Empire of it someday." However, another partner, Herbert Hislop, wrote in a letter that it was already called Empire Ranch when they bought it. Some think Edward Fish named it to make it sound grand. Others believe it was named after the nearby Empire Mountains.

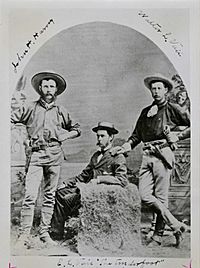

In October 1876, a wealthy Englishman named John H. Harvey joined the partnership. He had money to invest, even though he was new to ranching. The company changed its name to Vail, Hislop, and Harvey. Other ranchers called them the "English Boys' Outfit." They changed their horse brand to "VH" but kept a heart-shaped brand for their cattle.

Dealing with Apaches

In the early years, attacks from Apache Native Americans were a constant danger. Many nearby ranches closed down because of these threats. But the Empire Ranch stayed open and fought to protect its land and horses. Horses were especially valuable to the Apache warriors.

The Chiricahua Apaches had been moved to a reservation. But they often left and returned to their old lands in the mountains. These groups would raid ranches in the Cienega Valley. They would steal horses and escape into the hills. Ranchers who tried to get their horses back often failed or didn't return at all. Because of these raids, some ranchers near Empire Ranch left their homes. But Vail and Hislop were determined to stay.

The ranch was far from other towns, making it an easy target. It was a full day's ride from Tucson. The only other big ranch nearby was five miles away. Vail and Hislop knew help wouldn't arrive quickly if they were attacked. Their horses needed constant guarding. During the day, the horses grazed in a fenced area near the house. At night, they were brought into an adobe pen attached to the house. Losing their horses was a big worry for them.

The United States Army decided to act because of the Apache activity. In 1877, the army set up Camp Huachuca about 25 miles south of the ranch. This fort was meant to help stop the Indian trouble. However, it was still too far to protect the Cienega Valley directly. Vail and his partners refused to be scared away. They told their cowboys to always ride with weapons and never alone. Even when Apaches were reported nearby, they kept working.

The young ranchers didn't suffer too much from the Apaches. The Apaches raided nearby areas and stole some livestock. They also killed three cowboys south of the ranch. But they mostly avoided the Empire Ranch itself. It wasn't until Geronimo and his group surrendered in 1886 that the ranch owners felt completely safe.

In 1877, the ranch had a chance to grow its cattle herd. Walter Vail bought 793 cattle from a rancher named S. S. "Yankee" Miller. These cattle included different breeds like Durhams and Herefords. Vail also sold 620 sheep he owned, which had been a constant problem.

This cattle purchase had an exciting moment. Before Vail could move the herd, a group of Apaches quietly stole all of Miller's horses. Vail woke up before dawn to find them gone. Some of the trail crew tried to chase them, but they gave up. They feared the Apaches would outnumber them in the mountains. They returned to Empire Ranch to get more horses. Then they safely drove the new cattle to the ranch. In this close call, Vail was lucky. He only lost one horse, and no one was hurt.

Sheep and New Partners

In 1877, Vail, Hislop, and Harvey decided to bring better cattle breeds to their ranch. Walter Vail traveled to New Mexico and bought 40 Durham bulls. But he injured his knee and had to recover for five months. Later, he drove the bulls back to Empire Ranch.

While Vail was away, Hislop and Harvey had problems with a sheepherder who settled next to their land. This neighbor let his sheep wander onto the ranch's land to drink water. The sheep crowded the creek, forcing the cattle away from the water. Hislop was very angry. He warned the sheepman to stay off their land. He even threatened to stampede the sheep. The sheepman ignored him, and it looked like a range war might start.

In February 1878, Hislop wrote a letter saying he hoped no shooting would happen. He also mentioned that Walter Vail had returned and was very upset about the sheep. Hislop felt it needed an American to talk to another American, and that Vail meant "war to the knife."

Even though the dispute didn't turn into a fight, it made Hislop decide to leave ranching. He returned to England. Walter Vail borrowed money from his aunt to buy Hislop's share of the ranch. Hislop said he would never return to "this bloody country again."

Within a year, Walter's older brother, Edward "Ned" Vail, joined the ranch as a new partner. Ned had grown up on a farm and worked in New York City. Like Walter, he had no cattle experience when he arrived in 1879. Walter immediately put him to work on the range. This helped Edward learn the skills of a cattleman.

The Total Wreck Mine

While the ranch was getting ready to sell its first cattle, a silver discovery happened nearby. This greatly affected the ranch's future. In 1879, a prospector named John T. Dillon found three mining claims. They were on the eastern side of the Empire Mountains. Dillon said, "The whole damned hill is a total wreck." Walter L. Vail and John A. Harvey, who were also involved, liked the name. They called one of the sites the "Total Wreck."

After some legal issues, the owners started a company called the Total Wreck Mining and Milling Company. In 1881, Walter and Nathan Vail took full control of the company. They sold shares in New York City and started a big mining operation. Two years later, the mine was producing a lot of silver. It was as successful as the best mines in Arizona Territory.

However, silver prices dropped in 1884. This hurt the mine's operations. The Vails closed it three years later when it wasn't making enough money. Even though the Total Wreck mine only ran for a short time, it made over $500,000. This money helped a lot with expanding and developing the Empire Ranch.

Later Years and Today

In 1886, the ranch became a company called the Empire Land and Cattle Company. In 1889, a businessman named Carroll W. Gates bought half of it. The ranch started looking for new places to sell cattle in Kansas City and Los Angeles. This happened when the local market struggled in the 1880s. During dry years in the 1890s, Vail and Gates bought or leased more grasslands. These were in Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and California. Walter Vail also worked to help cattlemen as a lawmaker and president of the Livestock Ranchman's Association.

By 1898, the Vails had nearly 40,000 cattle, mostly Herefords. The home ranch focused on raising cattle to be sent elsewhere to get fatter. After 1902, they started investing in real estate, horse raising, and resorts on the West Coast. For a while, their California businesses made more money than the Arizona ranch. Walter Vail passed away in 1906. But his family continued to run the Empire Ranch successfully. They sold it in 1928 to the Boice, Gates and Johnston company.

By 1951, Frank Boice and his family owned the ranch completely. Around this time, the ranch became famous. It was used as a filming location for several Western films. Many famous Hollywood actors, like John Wayne, Gregory Peck, and Steve McQueen, filmed there.

In 1969, Empire Ranch was sold to a company that wanted to build houses. Later, it was sold again to a mining company. But none of these plans happened. The ranch continued to be used for cattle. In the 1980s, people started restoring the buildings to their original look. In 1988, the ranch became public land. It is now managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM).

In 1997, the Empire Ranch Foundation was created. This group works with the BLM to protect the buildings. They also help create educational and fun activities for the public. In 2000, Congress made the Empire Ranch part of the Las Cienegas National Conservation Area. The Vera Earl Ranch took over the grazing lease in 2008.

In April 2017, a large wildfire called the Sawmill Fire affected the Empire Ranch. This fire started from a gender reveal party. Luckily, the historic buildings were saved by firefighters. The fire came as close as 50 feet to the buildings.

Gallery