Euler's constant facts for kids

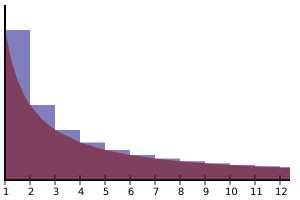

Euler's constant, also called the Euler–Mascheroni constant, is a special number in mathematics. It's usually shown with the Greek letter gamma (γ). This constant is found by looking at the difference between two things as they grow very large: the harmonic series and the natural logarithm.

Imagine adding up fractions like 1 + 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/4 and so on. This is the harmonic series. Now, imagine a special kind of logarithm called the natural logarithm. Euler's constant is what you get when you subtract the natural logarithm of a very large number from the sum of the harmonic series up to that number.

The value of Euler's constant, rounded to 50 decimal places, is:

Scientists are still trying to figure out if Euler's constant is a rational number (meaning it can be written as a simple fraction) or an irrational number (meaning it cannot).

Contents

History of Euler's Constant

The constant first appeared in a paper written in 1734 by the Swiss mathematician Leonhard Euler. He called it De Progressionibus harmonicis observationes, which means "Observations on Harmonic Progressions." Euler used the letters C and O to represent this constant.

Later, in 1790, an Italian mathematician named Lorenzo Mascheroni also studied this constant. He used the letters A and a. The symbol γ that we use today wasn't used by Euler or Mascheroni. It was chosen later, perhaps because the constant is connected to something else in math called the gamma function. For example, the German mathematician Carl Anton Bretschneider used γ in 1835.

Where Euler's Constant Appears

Euler's constant pops up in many different areas of mathematics and science. Here are a few examples:

- It appears in calculations involving special mathematical functions like the exponential integral.

- It's part of the Laurent series expansion for the Riemann zeta function, which is important in number theory.

- It's used when calculating the digamma function and the gamma function.

- You can find it in formulas that describe how fast certain mathematical functions grow.

- It's used in quantum field theory when scientists are doing complex calculations about tiny particles.

- It helps solve the coupon collector's problem, which is a fun math puzzle about how many coupons you need to collect to get a full set.

- It's also found in the study of how information is stored and measured, known as information entropy.

Properties of Euler's Constant

Mathematicians are still trying to understand some basic things about Euler's constant. For example, they don't know if γ is an algebraic number (a number that is a solution to a polynomial equation) or a transcendental number (a number that is not algebraic).

Even simpler, it's not known if γ is an irrational number. If it were a rational number (a fraction), its denominator would have to be incredibly large, more than 10244663! Because γ shows up in so many different math problems, figuring out if it's irrational is a big unsolved question in mathematics.

However, some progress has been made. In 2009, Alexander Aptekarev proved that at least one of Euler's constant γ or the Euler–Gompertz constant is irrational. In 2012, Tanguy Rivoal showed that at least one of them is transcendental.

Exponential Form

The number eγ (which is Euler's number e raised to the power of Euler's constant) is important in number theory. Its value is approximately:

This number is connected to prime numbers. For example, it's related to Mertens' theorems, which describe how prime numbers are distributed.

Continued Fraction

If you try to write Euler's constant as a continued fraction, it starts like this: [0; 1, 1, 2, 1, 2, 1, 4, 3, 13, 5, 1, 1, 8, 1, 2, 4, 1, 1, 40, ...]. This sequence of numbers doesn't seem to follow any clear pattern. Scientists have found at least 475,006 terms in this continued fraction. If Euler's constant is an irrational number, then its continued fraction will go on forever.

Published Digits

Mathematicians have worked hard over the centuries to calculate Euler's constant to more and more decimal places.

| Date | Decimal digits | Author | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1734 | 5 | Leonhard Euler | |

| 1735 | 15 | Leonhard Euler | |

| 1781 | 16 | Leonhard Euler | |

| 1790 | 32 | Lorenzo Mascheroni, with 20–22 and 31–32 wrong | |

| 1809 | 22 | Johann G. von Soldner | |

| 1811 | 22 | Carl Friedrich Gauss | |

| 1812 | 40 | Friedrich Bernhard Gottfried Nicolai | |

| 1857 | 34 | Christian Fredrik Lindman | |

| 1861 | 41 | Ludwig Oettinger | |

| 1867 | 49 | William Shanks | |

| 1871 | 99 | James W.L. Glaisher | |

| 1871 | 101 | William Shanks | |

| 1877 | 262 | J. C. Adams | |

| 1952 | 328 | John William Wrench Jr. | |

| 1961 | 1050 | Helmut Fischer and Karl Zeller | |

| 1962 | 1271 | Donald Knuth | |

| 1962 | 3566 | Dura W. Sweeney | |

| 1973 | 4879 | William A. Beyer and Michael S. Waterman | |

| 1977 | 20700 | Richard P. Brent | |

| 1980 | 30100 | Richard P. Brent & Edwin M. McMillan | |

| 1993 | 172000 | Jonathan Borwein | |

| 1999 | 108000000 | Patrick Demichel and Xavier Gourdon | |

| March 13, 2009 | 29844489545 | Alexander J. Yee & Raymond Chan | |

| December 22, 2013 | 119377958182 | Alexander J. Yee | |

| March 15, 2016 | 160000000000 | Peter Trueb | |

| May 18, 2016 | 250000000000 | Ron Watkins | |

| August 23, 2017 | 477511832674 | Ron Watkins | |

| May 26, 2020 | 600000000100 | Seungmin Kim & Ian Cutress | |

| May 13, 2023 | 700000000000 | Jordan Ranous & Kevin O'Brien |

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Constante de Euler-Mascheroni para niños

In Spanish: Constante de Euler-Mascheroni para niños

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |