John Couch Adams facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Couch Adams

|

|

|---|---|

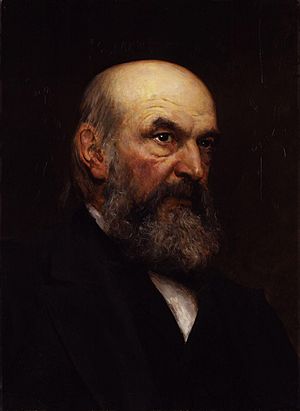

Adams c. 1870

|

|

| Born | 5 June 1819 Laneast, Cornwall, England

|

| Died | 21 January 1892 (aged 72) Cambridge Observatory, Cambridgeshire, England

|

| Known for |

|

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields |

|

| Institutions | |

| Academic advisors | John Hymers |

| Influences | Isaac Newton |

John Couch Adams (born June 5, 1819 – died January 21, 1892) was a brilliant British mathematician and astronomer. He was born in Laneast, a small village in Cornwall, England, and later passed away in Cambridge.

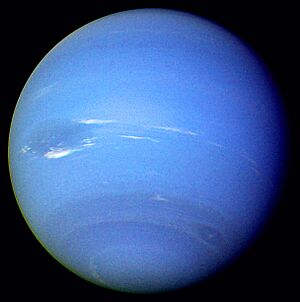

His most famous achievement was using only math to predict where the planet Neptune would be found. This was a huge step forward in astronomy!

Adams became a professor at the University of Cambridge in 1859 and held that position until his death. He received the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1866, a very important award for astronomers. In 1884, he represented Britain at a big meeting called the International Meridian Conference.

Today, a crater on the Moon is named after him and two other astronomers. Also, Neptune's farthest known ring and an asteroid called 1996 Adams are named in his honor. The Adams Prize at the University of Cambridge celebrates his amazing prediction of Neptune. His personal collection of books is kept at Cambridge University Library.

Contents

Early Life and Education

John Couch Adams was the oldest of seven children. He was born on a farm called Lidcot in Laneast, near Launceston, Cornwall. His parents, Thomas and Tabitha Adams, were not wealthy farmers. They were also devoted to their Methodist faith and loved music.

John's mother, Tabitha, had inherited a small library from her uncle, John Couch. Young John was fascinated by the astronomy books in this collection from a very young age.

He first went to the village school in Laneast, where he learned some Greek and algebra. When he was twelve, he moved to Devonport. There, he attended a private school run by his mother's cousin. While he studied classics, he mostly taught himself mathematics. He spent time in the Devonport Mechanics' Institute library, reading books like Rees's Cyclopædia.

In 1835, he saw Halley's Comet. The next year, he started making his own calculations and predictions about the stars. He even tutored others to earn money for his studies.

In 1836, his mother inherited some land. This allowed his parents to send him to the University of Cambridge. In October 1839, he started at St John's College. He graduated in 1843 as the top math student, known as the senior wrangler, and won the first Smith's prize that year.

Predicting Neptune's Location

In 1821, an astronomer named Alexis Bouvard published tables showing where the planet Uranus should be. These predictions were based on Newton's laws of motion and gravity. However, later observations showed that Uranus was not exactly where the tables said it should be. This made Bouvard think that another, unknown planet was pulling on Uranus, causing it to move differently.

Adams learned about these strange movements while he was still a student. He became convinced that this "pull" was real. He believed he could use the observed data of Uranus's path and Newton's laws of gravity to figure out the mass, position, and orbit of this hidden planet. On July 3, 1841, he wrote down his plan to solve this difficult problem.

After his final exams in 1843, Adams became a fellow at his college. He spent his summer vacation in Cornwall, working on the first of many calculations. Back in Cambridge, he continued his work while also tutoring students. He even sent money home to help his brothers get an education.

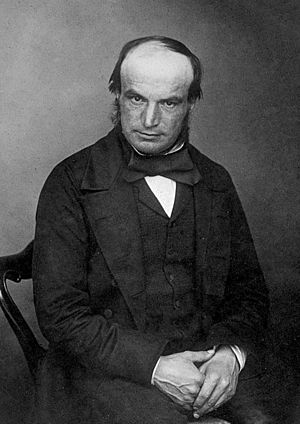

Adams shared his findings with James Challis, the director of the Cambridge Observatory, in September 1845. On October 21, 1845, Adams tried to meet with the Astronomer Royal, George Biddell Airy, in Greenwich. He couldn't find Airy at home, so he left a paper with his solution, but without all the detailed calculations. Airy wrote back asking for more information, but Adams did not reply. Some people think Adams was nervous or disorganized, which might explain why he didn't respond.

Meanwhile, in France, another astronomer named Urbain Le Verrier was working on the same problem. On November 10, 1845, he presented his own findings about Uranus's motion to the Académie des sciences in Paris. When Airy read Le Verrier's paper, he realized how similar it was to Adams's work. This started a race to find the planet first.

The search began in England on July 29, 1846. However, it was only after the discovery of Neptune was announced in Paris on September 23, 1846, that people realized it had actually been seen in Cambridge on August 8 and 12. But because Challis didn't have an up-to-date star map, he didn't recognize it as a new planet.

A big debate started in France and England about who deserved credit. As the full story became known, it was widely agreed that both Adams and Le Verrier had solved the problem on their own. Each was given equal importance for their work.

Adams himself publicly recognized Le Verrier's achievement. In November 1846, he spoke to the Royal Astronomical Society:

I mention these dates merely to show that my results were arrived at independently, and previously to the publication of those of M. Le Verrier, and not with the intention of interfering with his just claims to the honours of the discovery; for there is no doubt that his researches were first published to the world, and led to the actual discovery of the planet by Dr. Galle, so that the facts stated above cannot detract, in the slightest degree, from the credit due to M. Le Verrier.

Adams held no hard feelings toward Challis or Airy. He understood that he hadn't fully convinced the astronomy community:

I could not expect however that practical astronomers, who were already fully occupied with important labours, would feel as much confidence in the results of my investigations, as I myself did.

Later Scientific Work

Adams's fellowship at St John's College ended in 1852. However, Pembroke College elected him to a new fellowship the next year, which he held for the rest of his life.

Even with the fame from his work on Neptune, Adams also did important research on gravity in space and Earth's magnetism. He was very good at complex number calculations. He often improved the work of earlier scientists. However, he was not very competitive and was slow to publish his work.

In 1852, he published new and very accurate tables for the Moon's parallax. This work was better than previous tables. He hoped this would help him get a job as the head of the HM Nautical Almanac Office. But another person was chosen because Adams was not seen as a good organizer.

Understanding the Moon's Movement

For a long time, people thought the Moon's speed around Earth was constant. But in 1695, Edmond Halley suggested it was slowly speeding up. This effect became known as the secular acceleration of the Moon.

In 1853, Adams published a paper that showed a mistake in earlier calculations about the Moon's speed. He found that the Moon was speeding up less than previously thought due to gravity. At first, some scientists disagreed with him. But over time, Adams's findings were accepted. He showed that only about half of the observed speed-up could be explained by gravity. The rest, we now know, is due to tidal acceleration, which is the slowing down of Earth's rotation due to the Moon's pull. This important work earned him the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1866.

In 1858, Adams became a math professor at the University of St Andrews. But he only taught there for one term. He soon returned to Cambridge for the Lowndean professorship of astronomy and geometry. Two years later, he became the director of the Cambridge Observatory, a position he held until his death.

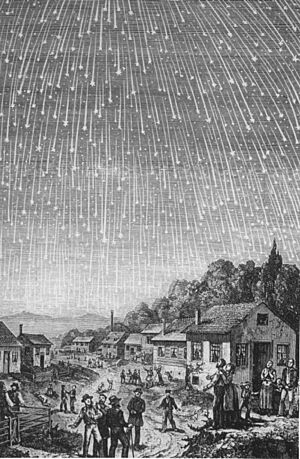

Studying the Leonids Meteor Shower

In November 1866, a spectacular meteor shower called the Leonids caught his attention. Other scientists had already guessed the path and timing of these meteors.

Adams used complex math to figure out that this group of meteors travels in a long, oval-shaped path around the Sun. It takes them 33.25 years to complete one orbit. Their path is also slightly changed by the gravity of large planets like Jupiter, Saturn, and Uranus. He published these results in 1867.

Many experts consider this one of Adams's most important achievements. His detailed calculations for the Leonids matched the orbit of a comet called 55P/Tempel-Tuttle. This suggested that comets and meteors are closely related, a idea that is now widely accepted.

Later Life and Legacy

Adams spent forty years working on calculations for Earth's magnetic field. These calculations were very difficult and were not published until after his death. His brother, William Grylls Adams, helped prepare them for publication.

Adams greatly admired Isaac Newton and his writings. Many of Adams's own papers show Newton's influence. In 1872, a collection of Newton's private papers was given to Cambridge University. Adams helped organize these important documents.

In 1881, he was offered the position of Astronomer Royal, a very prestigious job. But he chose to stay in Cambridge to continue his teaching and research. In 1884, he attended the International Meridian Conference in Washington, representing Britain.

Honors and Recognition

Adams received many honors for his scientific contributions:

- 1847: He was offered a knighthood by Queen Victoria but is said to have politely declined it.

- 1847: Became an Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

- 1848: Awarded the Copley Medal by the Royal Society, a very high honor.

- 1848: The Adams Prize was created by members of St John's College. This prize is given every two years for the best mathematical paper.

- 1849: Elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of London and an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

- 1851 and 1874: Served as President of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Family and Passing

After a long illness, John Couch Adams passed away in Cambridge on January 21, 1892. He was buried in the Parish of the Ascension Burial Ground in Cambridge. In 1863, he had married Miss Eliza Bruce, who outlived him and is buried with him.

Memorials

Many memorials honor John Couch Adams:

- A memorial with his portrait is in Westminster Abbey.

- A bust of him is in the hall of St John's College, Cambridge.

- Another bust belongs to the Royal Astronomical Society.

- Portraits of him can be found in Pembroke College and St John's College.

- A memorial tablet is in Truro Cathedral.

- The town of Launceston, near his birthplace, has a public institute named in his honor.

- Adams Nunatak, a rock peak in Antarctica, is also named after him.

Publications by Adams

- Adams, J. C., edited by W. G. Adams & R. A. Sampson (1896–1900) The Scientific Papers of John Couch Adams, 2 volumes, London: Cambridge University Press. This collection includes his previously published works and his lecture notes on the Moon's theory.

- Adams, J. C., edited by R. A. Sampson (1900) Lectures on the Lunar Theory, London: Cambridge University Press.

- A nearly complete collection of Adams's papers about the discovery of Neptune was given by his wife to the library of St John's College. These papers were later moved to the Royal Greenwich Observatory.

See also

In Spanish: John Couch Adams para niños

In Spanish: John Couch Adams para niños

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |