Frances Slocum facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Frances Slocum (Maconaquah)

|

|

|---|---|

Frances Slocum (age 66), portrait by George Winter, 1839

|

|

| Born | March 4, 1773 Warwick, Rhode Island, U.S.

|

| Died | March 9, 1847 (aged 74) Miami County, Indiana, U.S.

|

| Spouse(s) | Shepoconah (Deaf Man) |

| Children | two sons, died at a young age two daughters, Kekenakushwa (Cut Finger) (1800–1847) and Ozahshinquah (Yellow Leaf) (ca. 1809–1877) |

| Parent(s) | Jonathan Slocum (1733–1778) Ruth Tripp Slocum (1736–1807) |

Frances Slocum (March 4, 1773 – March 9, 1847) was also known as Maconaquah, which means "Young Bear" or "Little Bear." She was a white girl who was adopted by the Miami people. Frances was born into a Quaker family in Warwick, Rhode Island. In 1777, her family moved to the Wyoming Valley in Luzerne County, Pennsylvania.

On November 2, 1778, when Frances was just five years old, three Delaware warriors captured her. This happened at the Slocum family farm in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. Frances was raised among the Delaware people in what is now Ohio and Indiana. She later married Shepoconah, also known as Deaf Man, who became a Miami chief. When she joined the Miami tribe, she took the name Maconaquah. She settled with her new family at Deaf Man's village along the Mississinewa River near Peru, Indiana.

In 1835, Frances told a visitor that she was a white woman who had been captured as a child. Two years later, in September 1837, three of her siblings came to see her. They confirmed she was their long-lost sister. However, Frances chose to stay with her Miami family in Indiana. She had fully become part of the Native American culture and was accepted as one of them.

On March 3, 1845, the United States Congress passed a special law. This law allowed Frances and twenty-one of her Miami relatives to stay in Indiana. They were not forced to move to Kansas Territory. Her Miami relatives in Indiana were part of the group that formed the Miami Nation of Indiana today. Frances Slocum is buried at Slocum Cemetery in Wabash County, Indiana. Many places are named after her, including the Frances Slocum Trail and the Frances Slocum State Recreation Area in Indiana. There are also schools and a state park named after her.

Contents

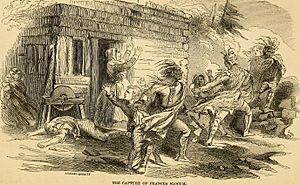

Early Life and Capture

Frances Slocum was one of ten children born to Jonathan and Ruth Slocum. She was likely born on March 4, 1773. Her family were Quakers, who believe in peace. They moved from Warwick, Rhode Island, to the Wyoming Valley in Pennsylvania in 1777.

Soon after they arrived, there was fighting in eastern Pennsylvania. Many people left during the Battle of Wyoming in July 1778. British forces and Seneca warriors destroyed Forty Fort near Wilkes-Barre. More than three hundred American settlers were killed. The Slocum family survived this battle. They believed their Quaker faith and good relations with Native Americans would keep them safe.

However, on November 2, 1778, three Delaware warriors attacked the Slocum farm. Frances's father was away at the time. Her mother and all but two of her children escaped into the nearby woods. But five-year-old Frances, her disabled brother Ebenezer, and a young boy named Wareham Kingsley were captured. Ebenezer was released at the farm. Frances and the Kingsley boy were taken away. Frances never saw her parents again. Her father and grandfather were killed later that year. Her mother, who died in 1807, never stopped hoping her daughter would be found.

The Delaware warriors gave Frances to a Delaware chief and his wife who had no children. They named her Weletasash, after their youngest daughter who had died. They raised Frances as their own child. We don't know much about Frances's early life with the Delaware. She later remembered traveling west through Niagara Falls and Detroit. They eventually settled near Kekionga, which is now Fort Wayne, Indiana.

Marriage and Family Life

Frances Slocum was briefly married to a Delaware man around 1791 or 1792. Miami tradition says this marriage did not work out. She returned to her Delaware parents. Her first husband is said to have moved west with the Delaware tribe.

Frances's second marriage was to She-pan-can-ah, known as Deaf Man. He was a Miami warrior who later became a chief. She met him when she found him badly hurt in the forest. With help from her Delaware parents, she brought him to their village. He stayed with them and got better. Frances eventually married him.

They had four children together. Their two sons died when they were young. Their two daughters, Kekenakushwa (Cut Finger) and Ozahshinquah (Yellow Leaf), lived to be adults. When Frances joined the Miami tribe, she took the name Maconaquah, meaning "Little Bear."

After the War of 1812, the Miami tribe moved to the Mississinewa River valley in north central Indiana. This included She-pan-can-ah and Maconaquah (Frances Slocum). We know little about Frances's life among the Native Americans during these years. Most of the information we have is from her later years. This is when she was reunited with her white relatives near Peru, Indiana, in 1837.

Later Years and Discovery

Frances Slocum's white relatives kept searching for her for many years. They did not see her for fifty-nine years. In 1835, Colonel George Ewing, an Indian trader, stopped at Deaf Man's village in Indiana. He spoke the Miami language well. During his visit, he talked with an elderly Miami woman. She told him she was born a white woman and had been kidnapped as a child. She spoke no English. But she remembered her white family's name was Slocum. She also remembered they were Quakers and lived along the Susquehanna River.

Ewing believed Frances wanted to share her secret. She had kept it for over fifty years. She was in poor health and thought she might die soon. Some people think she wanted to reveal her identity to save her Miami village. She might have feared they would be forced to move to the Kansas Territory. Or, she simply wanted to stay with her daughters in Indiana in her final years.

When Ewing met Frances, she was a widow. She lived with her family at Deaf Man's village. This small village had a double log cabin and other buildings. Living with her were her two daughters, Ozahshinquah and Kekenakushwa. Also living there were Kekenakushwa's husband, Jean Baptiste Brouillette, and three grandchildren.

Deaf Man's village was a place where different cultures met. Frances's family was not unusual. An African-American laborer who had married into the Miami tribe lived nearby. The village mixed European and Indian cultures because of the fur trade. But Frances was fully part of the Miami culture. The people in the village, including Frances, did not speak English. They were not Christian. They practiced their own traditions and ceremonies.

Reunion with Her White Family

After Ewing found Frances, he tried to find her white relatives. In 1835, he sent a letter to a postmaster in Pennsylvania. He asked if the Slocum family had a relative captured by Native Americans during the American Revolutionary War. The letter was lost for two years. When it was found, a notice was published in a newspaper. A minister in the Wyoming Valley saw it. He knew about the Slocum family's search for their sister. He sent the notice to Frances's brother, Joseph Slocum.

In September 1837, two of Frances's brothers, Isaac and Joseph, and her older sister, Mary Slocum Towne, traveled to Deaf Man's village. They brought interpreters with them. Frances was an elderly widow who had lived among Native Americans for almost sixty years. Frances, her two daughters, and a son-in-law also visited the Slocums while they were staying in Peru.

Frances's siblings were very happy to see her. But they were surprised by how much she had changed. She spoke no English and did not remember her Christian name, Frances. She spoke through an interpreter. Some people think she might have been afraid she would be forced to leave her Miami family.

During their visits, the Slocum family confirmed she was their lost sister. They recognized a disfigured finger on her left hand. This was from a childhood accident before she was captured. Her siblings tried to convince her to return to Pennsylvania. But she refused to leave her Native American family. Frances explained that she preferred to stay with the Miami. She said if she returned to her birthplace, she would be "like a fish out of water." In September 1839, Joseph Slocum and two of his daughters visited again. Frances still refused to leave. But she agreed to have her portrait painted.

Staying in Indiana

Treaties signed with the Miami in 1838 and 1840 meant Frances's community might have to move. They might be forced to leave Indiana for Kansas Territory. In these treaties, the Miami gave up most of their land in Indiana to the U.S. government. In 1840, they also agreed to move west of the Mississippi River within five years.

A treaty in November 1838 offered some Miami families land grants. This allowed them to stay in Indiana. Frances's two daughters, Ozahshinquah and Kekenakushwa, received 640 acres of land. This land meant they did not have to move to Kansas Territory. Frances was living with her daughters and was seen as the head of the family. But she was not named as a land recipient herself.

After it became known that Frances was white, her village tried to appear more white. This helped tribal leaders, like Miami chief Francis Godfroy, to delay the forced removal. It also helped some community members avoid moving to reservations west of the Mississippi River.

Frances asked her white brothers, Joseph and Isaac Slocum, for help. She wanted to ask the United States Congress to let her stay in Indiana. Her lawyer, Alphonzo Cole, presented her as an old woman who had suffered much. He said she only wanted to stay near her family, both white and Native American. U.S. Congressman Benjamin Bidlack of Pennsylvania supported her. He stressed that Frances should stay close to her white relatives, even though she had only met a few of them.

On March 3, 1845, Congress passed a special law. It allowed Frances and twenty-one members of her Miami village to stay in Indiana. Frances received 620 acres of land. With this approval, Frances and her Miami village could continue living on their land in Indiana. They were among the 148 people who formed the start of the Miami Nation of Indiana today.

The remaining Miami land in Indiana was given to the government in 1846. On October 6, 1846, a large group of over 300 Miami people were moved from Peru. A smaller group moved in 1847. In the end, less than half of the Miami tribe were moved. More than half either returned to Indiana or were never required to leave.

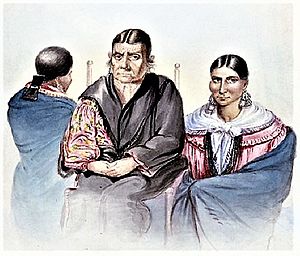

Portraits by George Winter

The Slocum family asked an English artist named George Winter to paint a portrait of Frances. Winter was one of the first professional artists to live and work in Indiana. He came to Logansport in 1837 to record the Indian removals in Indiana. Winter drew and wrote many descriptions of the Potawatomi and Miami people in his journals. These included drawings and details of Deaf Man's village, Frances, and her Miami family. His works are important sources for learning about Native American tribes in Indiana.

According to Winter's journal, his pencil sketch of Frances in her cabin in 1839 is the only one drawn from life. His portrait of Frances, called "The Captive Sister" or "Lost Sister of Wyoming," became very famous. He charged $75 for the painting. Winter's description of Frances in his journal matches his sketch: "Though bearing some resemblance to her family (white), yet her cheekbones seemed to have the Indian characteristics—face broad, nose bulby, mouth indicating some degree of severity, her eyes pleasant and kind."

He thought she was about five feet tall. He also noted the deep lines on her face and her hair, which was "originally of a dark brown, was now frosted." Winter also described her clothes. She wore a red shirt with yellow and green designs, a black skirt with red ribbon, and faded red leggings. She was barefoot and wore only earrings.

Winter used an African American interpreter to talk with Frances during the portrait sitting. Winter felt that his presence made the family uncomfortable. He wrote, "I could but feel as by intuition, that my absence would be hailed as a joyous relief to the family." Winter showed his sketch to Frances's Miami family. He noted that Frances "looked upon her likeness with complacency." Kekenakushwa, her oldest daughter, "eyed it approvingly, yet suspiciously." Her younger daughter, Ozahshinquah, refused to look, "as though something evil surrounded it."

Winter also sketched another version of Frances with her two daughters. The two portraits are different. In the formal oil portrait for the Slocum family, Frances looks serious. Her skin appears lighter, and her clothes are less colorful. In the other version, with her daughters, her face looks darker, and her clothing is more colorful. Her daughter Ozahshinquah, who refused to look at the first sketch, appears with her back to the artist. This was a common practice among Native Americans.

Death and Legacy

Frances Slocum died of pneumonia on March 9, 1847. She was 74 years old. She passed away at Deaf Man's village along the Mississinewa River in Indiana. Frances was first buried near her cabin, next to her second husband, She-pan-can-ah (Deaf Man), and their two sons. In 1965, their graves were moved to Slocum Cemetery. This was done because the Mississinewa River dam would flood the original site.

Frances Slocum's story is about a person who was captured and fully became part of the Native American culture. She was accepted as a member of their community. We don't know many details about her life among the Miami. This is perhaps because she told very little of her life to white people. Most of what we know about Frances's Miami community comes from outsiders like George Winter. His paintings and journals helped record parts of their lives and Miami culture.

An oral history of the Miami, written in the 1960s, tells more. It was told by Miami chief Clarence Godfroy, Frances's great-great-grandson. He described Frances as a woman respected by the Miami community, especially after her second husband died. People often went to her for advice. She also enjoyed breaking ponies and playing games with the men. This might have surprised American pioneers. But it was not unusual for women to have these roles within the Miami tribe.

Honors and Tributes

On May 6, 1900, Frances Slocum's descendants, both white and Native American, put up a monument at her gravesite. This is in Wabash County, Indiana. The monument honors her life as Maconaquah and Frances Slocum. It also remembers her second husband, She-pan-can-ah (Deaf Man). In 1967, a state historical marker was placed at the entrance to the Slocum Cemetery.

Other tributes named after her include:

- A thirty-mile long Frances Slocum Trail from Peru to Marion, Indiana.

- The Frances Slocum State Forest, a recreation area near Peru, Indiana.

- Frances Slocum State Park in Luzerne County, Pennsylvania.

A watercolor study of Frances Slocum and her two daughters by George Winter is part of the Tippecanoe County Historical Association's collections. An oil portrait of Frances Slocum is also there.