Gildersleeve Mountain facts for kids

Gildersleeve Mountain is a cool natural spot in Kirtland, Ohio, United States. It's special because it's a wild, beautiful place right next to a huge city area called Greater Cleveland. Even though millions of people live nearby, Gildersleeve Mountain feels untouched. It's one of only two places in the area with high hills and unique rock formations. It's a great spot for outdoor adventures and learning about nature.

Contents

Exploring Gildersleeve Mountain

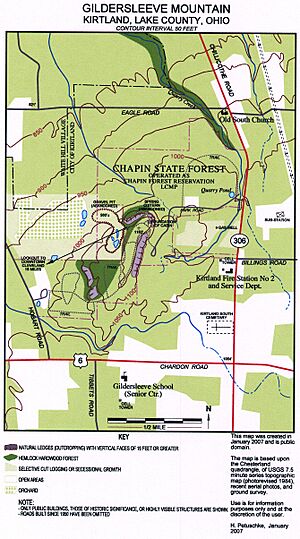

Gildersleeve Mountain is part of the Chapin Forest Reservation. This park is managed by Lake Metroparks and is often called the "scenic overlook." It's a perfect place for families and young explorers to visit. You can enjoy picnics, sports, and playgrounds, though these are not on the highest parts of the mountain. Many trails wind through the public lands, circling the summit. These trails are great for hiking, biking, horseback riding, and even cross-country skiing in winter!

Where is Gildersleeve Mountain?

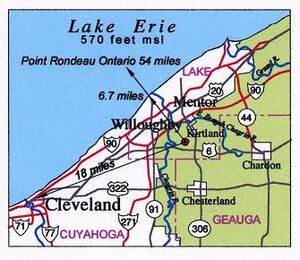

The very top of Gildersleeve Mountain is about 1,163 feet (354 meters) above sea level. That's about 593 feet (181 meters) higher than Lake Erie. Lake Erie's shoreline is only about 6.7 miles (10.8 kilometers) northwest of the mountain's peak.

Gildersleeve Mountain marks the start of the Allegheny Plateau in this area. Its northern sides slope down towards the Erie Plain. The southern side of the mountain isn't as steep, dropping only about 150 feet (46 meters) to the surrounding high lands.

Seeing the Mountain from Afar

Gildersleeve Mountain is one of the most noticeable natural features in the Cleveland area. On a clear day, you can see it from downtown Cleveland, Mayfield Heights, and even from the shores of Lake Erie. If you're on the lake looking south, or in a tall building near the lake in Cuyahoga County looking northeast, you'll spot it easily.

Amazing Views from the Top

From certain spots near the summit, you can see Lake Erie. One special viewpoint looks west and southwest, offering a clear view of the downtown Cleveland skyline, which is about 18 miles (29 kilometers) away. On very clear days, you might even see the tall stacks in Lorain or Avon Lake.

The closest point on the Canadian side of Lake Erie, Point Rondeau, Ontario, is about 54 miles (87 kilometers) away. However, from the lookout, you can only see about 28.7 miles (46.2 kilometers) to the horizon. So, while you can see the Canadian waters of Lake Erie, you can't quite see the Canadian shore itself. Sometimes, on clear nights, lights appear on the horizon to the northwest, but it's hard to tell if they are from Canada.

Years ago, the views to the north and east were amazing. You could see much of Kirtland and the Lake County shoreline. Sadly, trees have grown taller and now block some of these once-great views.

How Humans Changed the Mountain

Over time, people have changed the shape of Gildersleeve Mountain. A sand and gravel quarry on the west side was used for over 100 years, closing in 1968. The state of Ohio bought the land in 1949. Roads and some trails have been around for a long time, but others were added or changed by Lake Metroparks.

Logging, both clearcutting and selective cutting, has also changed the land. In 2006, about 40 acres (0.16 square kilometers) on the east side were selectively logged.

New homes have also changed the mountain's look, mostly on the southeast side. In 2007, the old quarry area and an orchard on the west side were turned into home sites.

There's also an old cabin foundation at the northern end of the summit. Its chimney fell down during a big storm in 1969. This storm also knocked down hundreds of trees on the mountain. The foundation is now hidden in an overgrown area that used to be a picnic spot with panoramic views. Even though signs still point to it, the view is now blocked by trees.

You can also find the remains of an old water tank (cistern) near some rocks west of the cabin foundation. Water from the rocks filters into this cistern.

Many small streams flow from Gildersleeve Mountain. They create ravines that cut through layers of rock. These ravines are interesting places to learn about the local geology.

Natural Wonders of Gildersleeve Mountain

Mountain's Ancient Story: Geology

Hundreds of millions of years ago, the area where Gildersleeve Mountain now stands was near the Earth's equator. It was part of the supercontinent Pangaea. Over time, the land changed from a deep ocean floor to a shallow sea. The rocks you see today tell this story.

The lowest rock layer is called Chagrin Shale. It's a blue-gray rock found deep below the mountain. Above that is Cleveland Shale, a black rock known for its fossils. You can find both of these in the nearby Chagrin River valley.

Next comes Bedford Shale, which is a sandy shale. It's found in the ravines on the mountain's slopes. Pieces of Bedford Shale often look like they were cut by hand because of their unique breakage pattern.

A thin layer of Sunbury Shale is sometimes found above the Bedford Shale. This black shale formed from very fine particles.

Berea sandstone is found higher up the mountain. This rock was once quarried from what is now Quarry Pond. It was used to build the Kirtland Temple and other local buildings. Berea sandstone is still used for building today.

The most striking rocks on Gildersleeve Mountain are the Sharon conglomerate formations. These rocks are sandstone mixed with white quartz pebbles. Scientists think they were formed by fast-moving streams carrying large pebbles and sand. These rocks make up the amazing ledges on the mountain's sides. Some of these rock faces are over 30 feet (9.1 meters) tall!

Glaciers also played a huge role in shaping Gildersleeve Mountain. During the Wisconsin glaciation, ice sheets more than a mile thick covered this region. These massive glaciers ground down the land, creating the Great Lakes. The hard Sharon conglomerate rocks were more resistant to this grinding.

Melted glacial ice also created huge floods that carved out ravines and filled others with clay and rocky debris. So, the Gildersleeve Mountain we see today is the result of millions of years of natural forces.

Plant Life: Flora

Before European settlers arrived, Gildersleeve Mountain was covered in a huge forest. This forest likely had three types of trees: beech-maple, hemlock hardwood, and oak-hickory. You can still find small groups of all three types today. Some very old oak and maple trees, untouched by 19th-century logging, can still be found. Most of the other trees are about 100 to 150 years old.

The hemlock hardwood forest is especially interesting. You can also find chestnut oak trees on the summit.

Many smaller plants grow here too. The most unique ones are found in the cool, damp cracks of the rock ledges. You'll see typical wildflowers like the bright red cardinal flower near creeks. Red and white trillium flowers grow where deer haven't eaten them. Other flowers include cress, foam flowers, blue cohosh, and sometimes even orchids. Many types of ferns also thrive here. Unfortunately, deer eating too many plants has reduced the number of these beautiful species. You can also find club mosses and lichens growing on the rock surfaces.

Interesting fungi also grow here, but they often disappear quickly because the mountain is so close to a big city.

Animal Life: Fauna

The small streams and wet areas on the mountain's slopes create special homes for animals. Dragonflies and damselflies are particularly interesting to nature lovers. New types of dragonflies have been discovered here, including the first tiger spiketail ever recorded in Ohio in 2004! Other rare dragonflies found here include the gray petaltail and comet darner.

Crayfish live in the creeks. While fish don't live in these shallow, fast-moving streams, you can find bluegills and largemouth bass in the ponds.

Many reptiles and amphibians also call Gildersleeve Mountain home. Salamanders live in the temporary pools of water that form in spring. You might see the red eft, a stage of the eastern newt, on the forest floor. Black rat snakes and garter snakes are common. One of Kirtland's first settlers wrote that rattlesnakes were common in the 1820s or 30s, but they soon disappeared. These were likely eastern timber rattlesnakes. American toads, spring peepers, and gray tree frogs are also found here. Pickerel frogs live in the creeks, and green frogs and bullfrogs are in the ponds.

Birds of Gildersleeve Mountain

Many types of birds live on Gildersleeve Mountain. Barred owls are common year-round. If you listen and watch carefully, you might spot them sitting quietly in the shadows. Cooper's hawks, red-shouldered hawks, broad-winged hawks, and red-tailed hawks also build their nests here. Wild turkeys nest on the mountain too.

You'll often see the amazing pileated woodpecker, as well as hairy, downy, and red-bellied woodpeckers. Great crested flycatchers, eastern phoebes, and Acadian flycatchers are common nesters. Eastern bluebirds are found in more open areas. Wood thrushes nest where trees create a canopy. Black-capped chickadees, tufted titmice, and white-breasted nuthatches are common residents. Red-eyed vireos often nest in treetops. Hooded warblers and American redstarts nest in the forest's lower plants. Ovenbirds nest on the forest floor, and Louisiana waterthrush nest in ravines and creek beds. Eastern towhees are found in the underbrush. Scarlet tanagers, rose-breasted grosbeaks, American goldfinches, house finches, and song sparrows also commonly nest here.

Rarer birds also nest here. Sharp-shinned hawks sometimes nest deep in the woods. A winter wren was found nesting in 2009. Blue-headed vireos are found in the ledges and hemlock trees. Hermit thrushes likely nest here too. Black-throated green warblers nest in the ledges and hemlock forests. Purple finches sometimes nest here. Dark-eyed juncos are very common year-round nesters on Gildersleeve Mountain, unlike in most of the Cleveland area where they are mostly winter visitors. A very rare nesting species, the pine siskin, was first confirmed in 2009.

Very rare birds that are just passing through (migrants) have also been seen from Gildersleeve Mountain. Tundra swans fly over in the fall on their way south. A northern harrier was seen in the spring. The most exciting sightings include a western kingbird in fall 2005 and a Kirtland's warbler in fall 2004. Uncommon winter visitors have included pine siskins, common redpolls, and evening grosbeaks.

Mammals You Might See

Gildersleeve Mountain is home to many mammals, both common and unexpected. You might see opossums, various shrews, moles, and several types of bats. Mice and voles are common, with the white-footed deer mouse being the most numerous. Red, gray (including black ones), and eastern fox squirrels are common. Southern flying squirrels are sometimes found. Eastern chipmunks are everywhere! Raccoons are also common. Three types of weasels (least, short-tailed, and long-tailed) have been found. Striped skunks are less common here than in suburban areas. White-tailed deer are common. Red foxes have become less common as coyotes have increased. There's even been evidence of bobcats, but they haven't been officially confirmed yet. In June 2004, a black bear was seen on Gildersleeve Mountain, leaving tracks and tearing up trash cans!

History of the Mountain

Gildersleeve Mountain is named after its first landowner, S.A. Gildersleeve.

- Prusha, Anne B., A History of Kirtland, Ohio. 1983, Lakeland Community College Press.

- Rosche, Larry (editor), Birds of the Cleveland Region. 2005, Cleveland Museum of Natural History

- Crary, Christopher, Memoir of Early Years of Settlement in Kirtland, 1893, [1]

- Szubski, Rosemary N. (editor), A Natural History of Lake County, Ohio. 2nd Edition 2002, Cleveland Museum of Natural History

- Foos, Annabelle M. (editor), Pennsylvanian Sharon Formation Past and Present...2003, Ohio Division of Geological Survey (Ohio Department of Natural Resources)

- Banks, P.O., Feldmann, Rodney M.(editors), Guide to the Geology of Northeastern Ohio. 1970 Northern Ohio Geological Society

- Camp, Mark J., Roadside Geology of Ohio. 2006, Mountain Press Publishing Company.

- Quarries of Chapin Forest [2]

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |