Kirtland's warbler facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Kirtland's warbler |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Male in Michigan, United States | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Parulidae |

| Genus: | Setophaga |

| Species: |

S. kirtlandii

|

| Binomial name | |

| Setophaga kirtlandii (Baird, 1852)

|

|

|

|

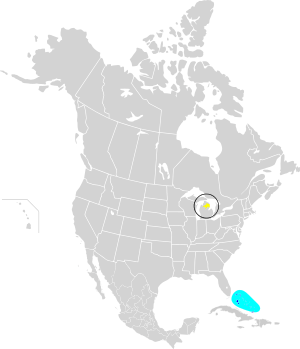

| The minimum range of S. kirtlandii in the early 1970s, as of 2019 the range has expanded considerably Breeding range Winter range | |

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The Kirtland's warbler (Setophaga kirtlandii) is a small songbird. People in Michigan used to call it the "jack pine bird" because it loves to live among jack pine trees. This bird is named after Jared Potter Kirtland, a doctor and nature lover from Ohio.

About 50 years ago, this bird was almost gone forever. But thanks to a lot of hard work, its numbers are now growing! Kirtland's warblers need large areas (bigger than 160 acres) of young, thick jack pine forests to raise their families. In the past, wildfires helped create these special forests. Today, people help by cutting down older jack pines and planting new ones.

These birds spend their spring and summer in places like Ontario, Wisconsin, and Michigan. When winter comes, they fly south to warmer places like The Bahamas and the Turks and Caicos Islands.

Contents

How It Got Its Name

The Kirtland's warbler was first officially described quite late for a bird from eastern USA. The first bird specimen was found in 1841 near the Abaco Islands. However, it wasn't recognized as a new species until much later.

Ten years later, in 1851, another young male bird was found near Cleveland, Ohio. A scientist named Spencer Fullerton Baird described it in 1852 and gave it the name Sylvicola kirtlandii. This bird was found on the farm of Jared Potter Kirtland, who was a famous naturalist.

Why the Name "Kirtland's Warbler"?

Spencer Fullerton Baird decided to name the bird after Jared Potter Kirtland. He said Kirtland had done more than anyone else to help us understand the natural history of the Mississippi Valley.

The scientific name Setophaga comes from ancient Greek words. Sḗs means "moth," and phagos means "eating." So, the name hints that these birds might eat moths.

What Does It Look Like?

Male Kirtland's warblers have a bluish-gray back with dark stripes. Their bellies are bright yellow, and they have dark stripes on their sides. They have black "cheeks" and a clear white ring around their eyes.

Female and young Kirtland's warblers look similar, but their backs and wings are a bit browner. Their markings are not as bright or bold as the males. These birds often bob their tails up and down, which is unusual for warblers in northern areas.

They are quite large for a warbler, about 14 to 15 centimeters (5.5 to 6 inches) long and weighing 12 to 16 grams (0.4 to 0.6 ounces). Their wingspan is about 22 cm (8.7 inches).

Their mating song is a loud chip-chip-chip-too-too-weet-weet. They often sing from the top of a dead tree or an oak tree. You can hear this song from over 400 meters (1,300 feet) away on a quiet day! In winter, they don't sing but make loud "chip" noises from low in bushes.

Their eggs are a light pinkish-white when new, fading to dull white. They have a few brown and pink speckles, mostly at the wider end. The eggs are about 18 by 14 millimeters (0.7 by 0.5 inches) and have very thin shells.

Birds That Look Similar

The Kirtland's warbler looks most like the Yellow-rumped warbler. You can tell them apart because the Kirtland's warbler has a mostly yellow belly and no bright yellow patch on its rump or crown. It also has a bigger, stronger beak and feet. In The Bahamas, it might sometimes be confused with the Yellow-throated warbler.

Where Does This Bird Live?

The Kirtland's warbler was first known only in Ohio. For a long time, its breeding area was very small, mainly in the northern part of Lower Peninsula of Michigan.

But now, thanks to conservation efforts, breeding pairs have been found in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, Wisconsin, and southern Ontario. This shows their population is growing and spreading!

In winter, these birds fly to The Bahamas and the nearby Turks and Caicos Islands. They have also been seen in the Dominican Republic. Sometimes, they are spotted in Florida, Bermuda, Cuba, and Jamaica.

The birds start their journey from The Bahamas in late April or early May. They fly west to Florida and South Carolina. From there, they move northwest, following the Mississippi River upstream to the Ohio River. They reach their breeding grounds in early June and leave between August and October.

Life in the Wild

Where It Makes Its Home

In their winter homes in The Bahamas, Kirtland's warblers mostly live in low, bushy areas called "coppice habitat." They especially like places that were once cleared for farming but have since grown back. They prefer dense bushes with small open spots, no tall trees, and low plants on the ground. They are almost always seen close to the ground, up to 3 meters (10 feet) high.

For breeding, they need large areas of young jack pine trees (6 to 20 years old, about 2–4 meters or 6–13 feet tall) growing on sandy soil. These warblers are found in the largest numbers where big areas have been clear-cut or where a large wildfire has happened.

Other common plants in their breeding habitat include blueberry, sweet fern, and various grasses. While it was once thought they only used jack pines, recent studies show they will also breed in young red pine stands that are 10 to 15 years old. When the pine trees grow too tall and lose their lower branches, the habitat is no longer good for them because it doesn't offer enough cover.

Daily Life and Habits

Young Kirtland's warblers and those breeding for the first time will explore to find new nesting spots. However, male birds that have been tagged often return to the exact same nesting place year after year. One male bird in Ontario returned to the same spot for six years in a row! This bird lived to be about nine years old, but most Kirtland's warblers don't live that long. Males usually live about four years, and females about 2.5 years.

One study found that most singing male warblers (85%) are able to find a mate.

A warbler pair will claim a breeding territory of about 2.7 to 3.4 hectares (6.7 to 8.4 acres). Their winter territory is larger, about 6.9 to 8.3 hectares (17 to 20.5 acres).

They build their nests on the ground, hidden very well by the lowest branches of the jack pines and other plants. The nest is usually at the base of a tree or next to a fallen log. Eggs are laid in May and June.

What's on the Menu?

In winter, the Kirtland's warbler eats a lot of berries from a plant called lantana. This plant is very common in fields that were once farmed but are now growing wild again. They also eat berries from black torch and snowberry plants.

In their summer breeding areas, these birds eat blueberries and insects like spittlebugs, aphids, and ants.

Friends and Foes in Nature

The Kirtland's warbler depends on jack pine trees. Jack pine cones only open after a forest fire or after trees have been cut down, allowing the summer sun to warm them.

One big problem for Kirtland's warblers is a bird called the brown-headed cowbird. Cowbirds are "brood parasites," meaning they lay their eggs in other birds' nests, including the warbler's. The warbler parents then raise the cowbird chicks, often at the expense of their own.

Blue jays also cause problems because they eat eggs and young birds from the nests. They can be a nuisance because they often get caught in traps meant for cowbirds.

Saving the Kirtland's Warbler

Why It Almost Disappeared

The Kirtland's warbler has always been a rare bird. It was first recorded quite late, between the 1840s and 1851. For the next two decades, only four or five birds were seen. The first nest wasn't even found until 1903 in Michigan.

It's a bit of a mystery how a species that needs such specific habitat managed to survive. It might be that during the Ice Ages, its habitat was more stable.

Interestingly, when Europeans first settled in Michigan, it might have actually helped the warbler for a while. Most of the Lower Peninsula of Michigan was once covered in huge old white pine forests. But these were all cut down by the early 1800s to build cities. This created perfect conditions for jack pine trees, which are "pioneer species" that grow quickly in cleared areas.

In the late 1800s, massive forest fires swept through Michigan. These fires destroyed the last of the old white pine forests. This period was probably the best time for the Kirtland's warbler, as it created lots of new jack pine habitat. Many warblers were collected during this time, mostly in The Bahamas or along their migration route.

In 1903, the first Kirtland's warbler nests were finally discovered near the Au Sable River in Michigan. This showed that Michigan was the main breeding area for these birds.

The Kirtland's warbler is very vulnerable to brown-headed cowbirds. Studies showed that a high percentage of warbler nests were being taken over by cowbirds. For example, one study found that 86% of warbler nests were parasitized. This meant fewer warbler chicks were surviving.

By 1971, the number of singing male warblers had dropped by 60% in just ten years. The population reached its lowest point in 1974, with only 167 singing males left.

Bringing Them Back: Recovery Efforts

In 1967, the Kirtland's warbler was listed as an endangered species in the USA. A recovery plan was created in 1971. This plan involved:

- Managing state and federal land by clear-cutting, controlled burning, and planting jack pine trees to create more nesting habitat.

- Buying more land for the warblers.

- Limiting public access to nesting areas during breeding season.

- Counting the warbler population every year.

- Controlling the number of cowbirds.

In 1972, efforts to control cowbirds began. Traps were used to catch cowbirds, which were then removed from the area. In the first year, over 2,200 cowbirds were removed, and the number of warbler nests taken over by cowbirds dropped from 69% to just 6%! The average number of eggs in warbler nests almost doubled. This program was a big success, and the warbler population started to increase for the first time.

Today, the warblers' habitat is no longer managed by controlled burns because they are too difficult to control. Instead, the birds rely completely on tree harvesting by the timber industry. About 76,000 hectares (188,000 acres) in Michigan are set aside for this purpose. The Michigan Department of Natural Resources and other groups work together to clear-cut 50-year-old jack pines. After cutting, new trees are planted in a special way to create the perfect mix of clearings and dense thickets that the warblers need.

The Kirtland's warbler population has steadily risen since the recovery plan began in the 1970s. In 2016, there were an estimated 5,000 Kirtland's warblers. By 2018, there were about 2,300 pairs. The population has been above the recovery goal of 1,000 pairs for 17 years!

The birds rely on The Bahamas for winter. Studies show there is enough habitat there for a very large population of warblers. However, house cats are a threat on some islands.

The cost of managing the habitat and controlling cowbirds is about $1 million per year. This cost is partly offset by money from timber companies who buy the jack pine wood. Also, the warblers bring bird-watching tourists to the area, which helps local businesses. To keep the warblers safe, this management will need to continue forever.

There's even a Kirtland's warbler festival in Roscommon, Michigan, held every June!

Kirtland's Warbler in Canada

Before 2007, Kirtland's warblers were not known to breed in Canada. The first bird was seen in Canada in 1900 on Toronto Islands. Over the years, there were a few more sightings, mostly at a military base called CFB Petawawa. In 1979, it was declared an endangered species in Canada.

Then, in 2006, three birds were seen at Petawawa. The next year, the first-ever nest was found there! It seems the habitat at this base has been kept suitable by fires from military training. Since 2007, the birds have bred almost every year at Petawawa, raising many young. They have also been reported in other parts of central Ontario.

The government of Ontario has a plan to help the Kirtland’s warbler. In 2018, a new forest of mixed red and jack pine trees was planted in Simcoe County to try and attract the warblers.

No Longer Endangered!

In 2019, the Kirtland's warbler was removed from the United States Fish and Wildlife Service list of endangered mammals and birds. This means it is no longer considered "endangered" under the Endangered Species Act. However, monitoring will continue to make sure the species stays safe and healthy.

Special Protected Places

Kirtland's warblers have been regularly seen in these protected areas:

- Abaco National Park, Abaco, The Bahamas.

- Algonquin Provincial Park, Ontario, Canada.

- Hartwick Pines State Park, Michigan, USA.

- Huron–Manistee National Forests, Michigan, USA.

- Lucayan National Park, Grand Bahama, The Bahamas.

- Point Pelee National Park, Essex County, Ontario, Canada.

- Rand Nature Centre, Grand Bahama, The Bahamas.

- Tawas Point State Park, Michigan, USA.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Reinita de Kirtland para niños

In Spanish: Reinita de Kirtland para niños

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |