Glen Canyon Park facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Glen Canyon park |

|

|---|---|

Aerial photograph of Glen Canyon Park; the Bosworth St., Sussex St., and Diamond Heights Shopping Center entrances are labeled. O'Shaughnessy Blvd. divides Glen Canyon Park (on the east) from O'Shaughnessy Hollow (to the west).

|

|

| Type | Municipal (San Francisco) |

| Location | San Francisco |

| Area | 70 acres (0.28 km2; 0.11 sq mi) |

| Created | 1922 |

| Open | All year |

| Official name: Site of the first dynamite factory in the US | |

| Reference #: | 1002 |

Glen Canyon Park is a city park in San Francisco, California. It covers about 70 acres (28 hectares) in a deep canyon. The park is next to the Glen Park, Diamond Heights, and Miraloma Park neighborhoods. O'Shaughnessy Hollow is a wild, undeveloped area of parkland. It is about 3.6 acres (1.5 hectares) and sits just west of Glen Canyon Park. Many people see it as part of the main park.

The park and hollow show what San Francisco looked like long ago. This was before many buildings were put up in the late 1800s and 1900s. The park has Islais Creek, which flows freely. It also has a special area along the creek called a riparian habitat. There is a large grassland with trees where red-tailed hawks and great horned owls build their nests. You can also see amazing rock formations and dry areas with "coastal scrub" plants. About 63 acres (25 hectares) of the park and hollow are protected as a Natural Area.

Glen Canyon Park goes from about 225 feet (69 meters) above sea level at the south end. It rises to 575 feet (175 meters) at the north end and along the canyon's eastern edge. The canyon walls are very steep. Some slopes are almost straight up and down.

Most of the park's sports and play areas are at its southern end. These include a community center, ball fields, tennis courts, playgrounds, and a ropes course. Rock climbers also love the park. They say it's one of the best places for "bouldering" (climbing on large rocks) near San Francisco. Another building near Islais Creek is used by the Silver Tree Day Camp and the Glenridge Cooperative Nursery School.

It's easy to enter the park from its southeastern corner (at the end of Bosworth Street). Further north, there is a wooden stairway leading into the park (the Sussex Street entrance). You can also find trails into the park from the Diamond Heights Shopping Center. One trail offers a "dramatic, sudden revelation of the park interior from high up, which is simply stunning." This entrance is in the middle of the park, behind the Diamond Heights Shopping Center.

Contents

Islais Creek: San Francisco's Wild Waterway

A part of Islais Creek starts in Glen Canyon. The creek is named after the wild cherry tree called islay. It is the largest creek in San Francisco that people can visit. The bottom of the canyon, where Islais Creek flows, is uneven but slopes gently. It drops 350 feet (107 meters) over about 1 mile (1.6 kilometers). Willow trees grow all around the creek.

Long ago, the creek had more water and was "more of a river than a creek." But city growth has reduced the amount of water flowing into Islais Creek by as much as 80 percent. At the south end of the canyon, Islais Creek goes into a large underground pipe. This pipe carries the water all the way to San Francisco Bay.

Wildlife: Animals of Glen Canyon Park

The creek has a small but steady flow of water all year. This water and the plants around it create a home for many animals. You might see skunks, opossums, raccoons, red-tailed hawks, red-shouldered hawks, great horned owls, and coyotes. The park is also home to the rare native San Francisco forktail damselfly, Ischnura gemina.

Geology: The Park's Amazing Rocks

Glen Canyon Park is famous for its many large rock formations. The most impressive ones are made of reddish, layered rock called "Franciscan" chert. These rocks have clear stripes that you can see. These stripes are caused by how the different layers have worn down over time.

The main rock beneath the canyon is part of the Marin Headlands terrane. A terrane is a large block of rock that has moved a long distance. This one stretches from the Marin Headlands (north of the Golden Gate) through the Twin Peaks and Glen Canyon area. It then continues to the southeast. This rock block is very old, between 100 and 200 million years old. This means it formed during the Cretaceous and Jurassic periods.

The rocks on the lower slopes of the canyon are mostly hidden. They are made of pillow lava or greenstone. These rocks formed from lava that erupted from cracks on the deep ocean floor. This happened when the terrane was hundreds of miles southwest of where it is now.

The upper slopes and cliffs are made of layered chert. This rock formed from the gooey remains of tiny sea creatures called radiolaria. These remains piled up on top of the lava. The goo turned red because of iron from hot water springs deep in the ocean. Both the lava and the chert formed in the deep ocean near the equator. They slowly moved northeast on the ocean floor towards California.

Near the coast, another type of rock called greywacke built up on top of the chert in some places. This includes a small part of the southeast slope of Glen Canyon. Then, a process called Subduction pushed the terrane against the continent. It eventually became part of the Franciscan formation, which makes up much of coastal California. During this process, from 160 to 80 million years ago, the terrane was twisted and broken. The chert was bent into the tight folds you can see in the road cuts along O'Shaughnessy Boulevard.

These rock formations are some of the best places for outdoor rock climbing in San Francisco. Most of the climbing here is bouldering, which means climbing on large rocks close to the ground.

History: How Glen Canyon Park Came to Be

Sutro's Gum Tree Ranch

The park's story began in the 1850s when Adolph Sutro bought about 76 acres (31 hectares) of the canyon. He called it "Gum Tree Ranch" because he planted many blue gum eucalyptus trees there.

Giant Powder Company: A Blast from the Past

The first company in the U.S. to make dynamite started in this canyon. On March 19, 1868, the Giant Powder Company began making dynamite. They had a special agreement with Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite, to make his new explosive in America. The factory was likely near where the recreation center is today, at the park's south end.

The factory did not last long. On November 26, 1869, a huge explosion completely destroyed the entire factory. A newspaper said that every building and fence turned into "hundreds of pieces." Two people died, and nine were hurt. The factory was later rebuilt in the sand dunes south of Golden Gate Park. The site of the old factory is now a California Historical Landmark (#1002). However, there is no marker there yet.

The Crocker Era: From Amusement Park to Picnic Spot

In 1889, the Crocker Real Estate Company bought the canyon. They wanted to build a neighborhood there. But first, they created a mini-amusement park! It had an aviary (for birds), a mini-zoo with bears, elephants, and monkeys, and a bowling alley. For extra excitement, they offered hot-air balloon rides and had a brave tight-rope walker perform across the canyon.

From 1907 to 1922, Glen Canyon Park was used as a picnic ground, mostly for adults. Crocker Real Estate added tables, benches, a baseball field, and a running track. It was fenced off and rented to groups for company picnics. These picnics often became noisy parties. Neighborhood children had to find other places to play.

City Park: A Place for Everyone

The Crocker era ended in 1922 when the City of San Francisco bought the 101-acre (0.41 km2) Glen Canyon Park and Recreation site. Today, O'Shaughnessy Boulevard forms the western edge of Glen Canyon Park. This road, along with an extension of Bosworth Street, was built in 1935. It used road cuts and filled slopes on the canyon's steep sides. The boulevard was named after Michael O'Shaughnessy, who was the city's Chief Engineer for many years. The recreation center at the park's south end was built in 1937 by the Works Progress Administration, a government program that created jobs during the Great Depression.

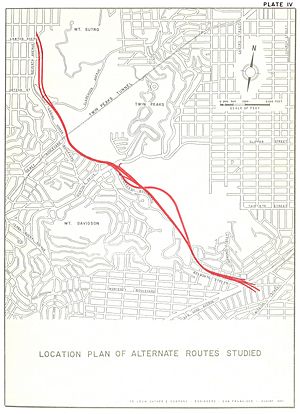

In 1958, the California State Highway Department planned a "Crosstown Freeway." It would have gone through the Glen Park neighborhood and then O'Shaughnessy Boulevard, right through Glen Canyon Park. But many groups of residents protested, and the plan was stopped. Six other freeways planned for San Francisco were also canceled around the same time. These protests were some of the first "Highway revolts in the United States" that happened across the country in the 1960s and 1970s.

Six years later, in 1964, homes and businesses along Bosworth Street were torn down. This was done to make that part of the street much wider, leading to O'Shaughnessy Boulevard.

In the 1990s, the City of San Francisco bought a very steep, undeveloped area just west of O'Shaughnessy Boulevard. The city used a process called eminent domain to buy the land, which was being considered for houses. This 3.6-acre (1.5-hectare) area was named O'Shaughnessy Hollow.

Future of the Park: Protecting Nature

The San Francisco city government decided to create plans for all its "natural areas." This led to the Significant Natural Resources Areas Management Plan in 2006. This plan aims to bring back native plants and animals to the city's parks. Some parts of the plan have caused debate. For example, the plan suggests removing some large, old trees (like eucalyptus, which came from Australia). This would make more room for smaller native plants.

The plan also includes new rules for how people can use the park. Some trails might be closed, and some rock climbing areas might be off-limits. There might also be rules against letting dogs run without leashes.

In Glen Canyon Park, about 20 large eucalyptus trees were removed in 2004. This was part of an effort to help more types of plants and animals live along Islais Creek. The plan suggests removing another 120 trees (out of 6,000 in the park). This would further improve the creek, make the park's grasslands bigger, and help plants grow under the forest trees. The plan also wants to bring back some open water areas along the creek. Today, the creek is almost completely hidden by willow trees. Changes to the creek would involve planting different plants along its banks and adding structures to help the water flow better.

Glen Canyon Park used to have two rare insects: the "vulnerable" San Francisco forktailed damselfly and the "endangered" Mission blue butterfly. The plan suggests ways to manage the park to help these insects thrive again. Scientists studied the damselfly population in the park in the 1980s before it disappeared from the area. They brought damselflies back in 1996, and they lived there for two seasons. Damselflies need open water, which has been hard to keep in the park.

The Mission blue butterfly population has been decreasing at the nearby Twin Peaks Natural Area. Park workers counted about 150 butterflies in the 1980s. But between 2001 and 2007, only four were found. In April 2009, some butterflies were brought back to Twin Peaks. It might also be possible to bring them back to Glen Canyon Park. To do this, the park needs to bring back the native plant "silver bush lupine." The leaves of this plant are the only food for the butterfly larvae (caterpillars).

A large part of Glen Canyon Park is now covered by plants that are not native to the area. These include eucalyptus trees (17 acres), French broom (6 acres), and field mustard. However, the Management Plan did not include a specific proposal for bringing back the lupine plant.

Urban Planning: Connecting Park and Community

Glen Canyon Park is very important to the neighborhoods around it. A recent plan for the Glen Park community shows this. It says that the special feeling of Glen Park comes from its unique buildings, walking-friendly streets, green spaces, and closeness to the canyon and public transport. Any new building project, whether public or private, must include these features.

A section of Bosworth Street connects the southern entrance of Glen Canyon Park to the main shopping area of Glen Park. This area is about a third of a mile east. This section is a great chance for urban design. The land along the north side has been empty since the city bought it in the 1950s. The community plan suggests turning this land into a greenway and a pedestrian plaza (a public square for walking). The plan also suggests that Islais Creek, which flows underground beneath this part of Bosworth Street, could be "daylighted" here. This means bringing the creek back to the surface so people can see it. The San Francisco Planning Commission officially supported this plan in 2004. However, as of 2007, there was no money to make it happen.

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |