Grace Mary Crowfoot facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Grace Mary Crowfoot

|

|

|---|---|

| Born |

Grace Mary Hood

1879 Lincolnshire, England

|

| Died | 1957 Geldeston, Norfolk

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Archaeology, botany |

Grace Mary Crowfoot (née Hood; 1879–1957) was a very important person who studied ancient fabrics. These old fabrics are called archaeological textiles. Her friends and family always called her Molly.

Molly worked on many different textiles from places like North Africa, the Middle East, Europe, and the British Isles. She lived in Egypt, Sudan, and Palestine for over 30 years. When she returned to England in the 1930s, she continued her work.

She helped write an article in 1942 about a tunic from the famous pharaoh Tutankhamun's tomb. She also published short reports about textiles found at the Sutton Hoo ship burial site in Suffolk, England.

Molly Crowfoot taught many people in Britain how to study ancient textiles. Her students included Audrey Henshall and her own daughter Elisabeth. She also worked closely with textile experts in Scandinavia, like Margrethe Hald and Agnes Geijer.

Together, they created a new field of study. They made sure that any fabric pieces found at old sites were saved for study. Before this, these delicate pieces were often just cleaned off metal objects and lost. Much of Crowfoot's collection of textiles and tools for spinning and weaving is now kept at the Textile Research Centre in Leiden.

Her daughter, Dorothy Hodgkin, became a famous chemist. Dorothy won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1964. After Molly's death, her life and work were remembered in articles by archaeologist Kathleen Kenyon and her son-in-law, Thomas Hodgkin.

Contents

Early Life and Interests (1879–1908)

Grace Mary Hood was born in Lincolnshire, England, in 1879. She was the oldest of six children. Her family, the Hoods, were wealthy landowners from Yorkshire. Her nephew, Sinclair Hood, later became a well-known archaeologist too.

Molly's grandfather, Reverend William Frankland Hood, collected ancient Egyptian items. He even added a special part to their family home, Nettleham Hall, to display them. Because of her family's interests, Molly met many archaeologists. One of them was William Flinders Petrie. She became lifelong friends with his wife, Hilda.

Elizabeth Wordsworth offered Molly a place at Lady Margaret Hall. This was a new college for women at Oxford University. However, Molly's mother did not think women needed to go to university, so Molly did not attend.

Molly's first experience with archaeology was in 1908–1909. She dug up prehistoric remains in a cave called Tana Bertrand. This cave was above San Remo on the Italian Riviera, where her family often stayed. She found 300 beads and signs that people lived there a long time ago. Her findings were not published until 1926.

In 1908, Molly decided she wanted to help society. She trained to become a professional midwife at Clapham Maternity Hospital in London. The people she met during this training later helped her when she lived in Sudan.

Life and Work in Egypt and Sudan

In 1909, Molly Hood married John Winter Crowfoot. She had met him years before in Lincoln. John was then the Assistant Director of Education in Sudan. Molly joined him in Cairo, Egypt. Their first three daughters, Dorothy, Joan, and Elisabeth, were born there. A person who knew the Crowfoots in Sudan described Molly as "that gracious, unassuming, well-educated lady."

Crowfoot's Activities

Molly Crowfoot learned to take photographs. These pictures were used in her first books about plants. She wrote several books about plants during her years in Egypt, Sudan, and Palestine. Later, she preferred to use her own drawings in her publications. She felt drawings could show the details of plants and flowers more clearly than photos. After she died, many of her drawings of wild plants from North Africa and the Middle East were given to Kew Gardens in London.

In 1916, during the First World War, Molly and John moved to Sudan. It was far from the fighting and away from the European community in Cairo. There were few white people in Khartoum, and no white women. Her husband was in charge of education and ancient objects in the region. He became the Director of Gordon Memorial College (now Khartoum University).

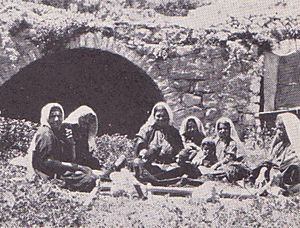

Molly spent time with the local women across the Nile River in Omdurman. To talk with them, she started learning about their spinning and weaving. This was a big part of their daily lives. Molly became a skilled weaver herself, learning to make cloth on simple looms. She later published two papers about these techniques.

At the request of archaeologist Flinders Petrie, she compared these methods with ancient Egyptian spinning and weaving. A model showing these methods had recently been found in an 11th dynasty tomb. Molly found that the techniques and tools had changed very little since ancient times.

Family Life and Return to England

After their fourth daughter, Diana, was born, and World War I ended, Molly and John returned to England for a few months. They were reunited with their three older girls. They rented a house in Geldeston, Norfolk. This house became their family home for the next sixty years. Soon after, they returned to Sudan.

Life and Work in Palestine (1926–1935)

In 1926, John Crowfoot was offered a job as the Director of the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem. During his time there, he led several important excavations. These included digs at Samaria-Sebaste (1931-3 and 1935), the Jerusalem Ophel (1927), and early Christian churches in Jerash (1928–1930).

Molly Crowfoot was in charge of organizing living and food arrangements at the dig sites. She managed large groups of archaeologists from the UK, Palestine, and US universities. Molly and John were admired for their skills in working with different groups. Molly was very interested in the objects found. She was one of the authors and editors of the final three large books about the Samaria-Sebaste excavations.

While living in Jerusalem, Molly Crowfoot collected folk tales with her friend Louise Baldensperger. Louise's parents had settled in the country in 1848. Together, Molly and Louise wrote From Cedar to Hyssop: A study in the folklore of plants in Palestine (1932). This was an early book about how people use plants in their culture, known as ethno-botany. Many years later, the tales they collected were translated back into Arabic and published again.

An Active Retirement

John and Molly Crowfoot returned to England in the mid-1930s. They were back in time to see their two oldest daughters get married. They also welcomed the first of their 12 grandchildren.

Their family home in Geldeston, called the Old House, had many visitors over the next 20 years. One visitor was Yigael Yadin, the son of their friend Eleazer Sukenik. Sukenik was a Jewish archaeologist who worked with them on the Samaria-Sebaste excavations.

Molly Crowfoot always took an interest in village activities during their long summer visits in the 1920s and 1930s. In 1925, she started a local branch of the Girl Guides. She remained active in her retirement. She regularly attended church. During wartime, she was the secretary of the new Village Produce Association, which encouraged people to grow their own food (like "Digging for Victory"). After the war, she became chairwoman of the local Labour Party.

During Molly Crowfoot's last years, she was often in bed. She battled childhood tuberculosis and later leukaemia.

Her daughter Elisabeth helped her examine and study many textile samples. These samples were sent to the Old House from various archaeological digs. As a leading expert in ancient Middle-Eastern textiles, Molly was asked in 1949 to examine the linen wrappers of the Dead Sea Scrolls. She published a lively first report in 1951. A full description and analysis appeared in 1955.

Molly Crowfoot died in 1957. She is buried with her husband John next to the church of St Michael and All Saints in Geldeston.

Papers, Photos, and Textile Collection

- Molly Crowfoot's unpublished papers about her time in Egypt, Sudan, and Palestine are kept at the Sudan Archive at Durham University Library. You can see the list of her papers there. Many of the photos she took are held at the Palestine Exploration Fund archives in London.

- Many of Crowfoot's drawings of plants from North Africa and the Middle East were given to Kew Gardens after her death. Some of the Palestinian costumes she collected were given to the former Museum of Mankind. Crowfoot's collection of textiles and tools for spinning and weaving is now kept at the Textile Research Centre in Leiden, Netherlands.

About Molly Crowfoot

- Kathleen Kenyon, obituary

- Thomas Hodgkin, obituary

- Elisabeth Crowfoot, "Grace Mary Crowfoot", Women in Old World Archaeology, 2004. For the complete text, with a full list of Crowfoot's publications, see the linked pdf file. A summary and selected photos are available online.

- Amara Thornton (2011), British Archaeologists, Social Networks and the Emergence of a Profession: the social history of British archaeology in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East, 1870–1939 (PhD in Archaeology, UCL Institute of Archaeology). This study focuses on five British archaeologists: John Garstang, John Winter Crowfoot, Grace Mary Crowfoot, George Horsfield, and Agnes Conway.

- John R. Crowfoot (2012), "Grace Mary Crowfoot", entry in Owen-Crocker G., Coatsworth E. and Hayward M. (eds), Encyclopaedia of Mediaeval Dress and Textiles of the British Isles, Brill: Leiden, 2012, pp. 161–165.

See also

In Spanish: Grace Mary Crowfoot para niños

In Spanish: Grace Mary Crowfoot para niños

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |