Great Mosque of Djenné facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Great Mosque of Djenné |

|

|---|---|

|

الجامع الكبير في جينيه

Grande Mosquée de Djenné |

|

The Great Mosque's signature trio of minarets overlooks the central market of Djenné.

|

|

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Islam |

| Status | In use |

| Location | |

| Location | Djenné, Mopti, Mali |

| Architecture | |

| Architectural type | Mosque |

| Architectural style | Sudano-Sahelian |

| Completed | 13th–14th century; rebuilt in 1906 |

| Specifications | |

| Height (max) | 16 metres (52 ft) |

| Minaret(s) | 3 |

| Materials | Adobe |

The Great Mosque of Djenné is a huge building made of mud bricks in Djenné, Mali. It's built in a special style called Sudano-Sahelian, which uses earth and wood. You can find it on the flood plain near the Bani River.

The very first mosque on this spot was built around the 13th century. But the building you see today was finished in 1907. It's not just a place for prayer; it's also a famous landmark in Africa. In 1988, UNESCO named it a World Heritage Site, along with the "Old Towns of Djenné."

Contents

History of the Great Mosque

The First Mosque Building

We don't know the exact year the first mosque in Djenné was built. Some guess it was as early as 1200, while others say it was closer to 1330. The oldest record about it comes from a book called Tarikh al-Sudan. This book shares stories passed down through generations.

It says that a ruler named Sultan Kunburu became a Muslim. He decided to tear down his palace and build a mosque in its place. He then built a new palace for himself nearby. The next ruler added the mosque's towers, and the one after that built the surrounding wall.

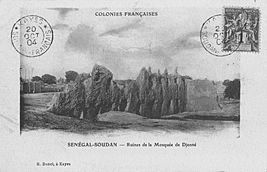

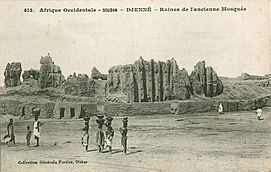

We don't have much more information about the mosque until 1828. That's when a French explorer, René Caillié, visited Djenné. By then, the mosque was in ruins. Caillié wrote that it was "rudely constructed" and full of swallows. Because of the bad smell, people prayed in a small outdoor area instead.

Seku Amadu's Mosque

About ten years before René Caillié's visit, a Fulani leader named Seku Amadu took control of Djenné. Seku Amadu didn't like the old mosque. He let it fall apart, which is why Caillié saw it in ruins. Seku Amadu also closed all the smaller mosques in the area.

Between 1834 and 1836, Seku Amadu built a new mosque. It was located to the east of the old one, where the former palace used to be. This new mosque was a large, low building without any towers or fancy decorations.

In 1893, French forces took over Djenné. Soon after, a French journalist, Félix Dubois, visited the town. He described the ruins of the first mosque. At that time, the inside of the ruined mosque was used as a cemetery. In his 1897 book, Dubois even drew what he thought the mosque looked like before it was abandoned.

The Mosque Today

In 1906, the French leaders in Djenné decided to rebuild the original mosque. They also built a school where Seku Amadu's mosque used to be. The rebuilding of the mosque was finished in 1907. It was done by forced labor, led by Ismaila Traoré, who was the head of Djenné's group of masons.

Pictures from that time show that some of the outer walls followed the lines of the first mosque. But it's not clear if the inside pillars were in the same places. What was definitely new were the three large, evenly spaced towers on the qibla wall. This is the wall that faces Mecca. People have debated how much the French influenced the new design.

Dubois visited Djenné again in 1910 and was surprised by the new building. He thought the French had designed it. He even joked that it looked like a mix between a hedgehog and a church organ! However, others, like Jean-Louis Bourgeois, believe the French had very little influence. They say the design is "basically African."

A French researcher, Michel Leiris, wrote in 1931 that the new mosque was indeed built by Europeans. He also said that local people were so unhappy with it that they refused to clean it. They only did so when threatened with prison.

But Jean-Louis Bourgeois said that the local masons of Djenné built the mosque. These masons have a long history of building and taking care of the town's structures. He said they used traditional methods with very little help from the French.

The open area in front of the mosque's eastern wall has two tombs. The larger tomb holds the remains of Almany Ismaïla, an important religious leader from the 1700s. Long ago, there was a pond on the eastern side of the mosque. It was filled in to create the open space now used for the weekly market.

Many mosques in Mali have added electricity and indoor plumbing. Sometimes, the old surfaces of a mosque are even covered with tiles. This can ruin its historical look and even damage the building. The Great Mosque of Djenné has a loudspeaker system. But the people of Djenné have chosen to keep their mosque looking historical. They want to protect its original design. Many people who work to save old buildings have praised this effort. Interest in how the building is preserved grew in the 1990s.

In 1996, Vogue magazine had a fashion shoot inside the mosque. The pictures of models in revealing clothes upset the local people. Because of this, non-Muslims have not been allowed to enter the mosque since then. The mosque also appears in the 2005 movie Sahara.

On January 20, 2006, a team was inspecting the roof of the mosque. This was part of a repair project. Seeing them on the roof caused a big disturbance in the town. People removed the ventilation fans that had been given by the US Embassy. Then, they caused damage around the town. The local police had to call for help from another city.

On November 5, 2009, the top part of the southern large tower on the qibla wall fell down. This happened after a lot of rain fell in one day. The Aga Khan Trust for Culture helped pay to rebuild the tower.

The mosque is so important that it is even shown on the coat of arms of Mali.

Design of the Mosque

The walls of the Great Mosque are made from sun-baked earth bricks. These bricks are called ferey. They are held together with a mortar made of sand and earth. The whole building is covered with a smooth plaster. This gives it a sculpted look.

The walls are decorated with bundles of rodier palm sticks. These sticks are called toron. They stick out about 60 centimeters (2 feet) from the wall. The toron are also very useful. They act like ready-made scaffolding for the yearly repairs. Ceramic half-pipes also stick out from the roof. They help direct rainwater away from the walls.

The mosque sits on a platform about 75 by 75 meters (246 by 246 feet). This platform is raised about 3 meters (10 feet) above the market. This helps protect the mosque when the Bani River floods. You can reach the platform by six sets of stairs. Each set of stairs has decorative points at the top. The main entrance is on the north side of the building. The outer walls of the mosque are not perfectly straight. This gives the building a slightly trapezoid shape.

The prayer wall, or qibla, faces east towards Mecca. It looks out over the city marketplace. This wall has three large, box-like towers called minarets. The middle tower is about 16 meters (52 feet) tall. The cone-shaped tops of each minaret are decorated with ostrich eggs. The eastern wall is about 1 meter (3 feet) thick. It is made stronger by eighteen buttresses on the outside. Each buttress has a decorative point at the top. The corners of the mosque have rectangular buttresses. These are also decorated with toron and topped with points.

The prayer hall is about 26 by 50 meters (85 by 164 feet). It takes up the eastern half of the mosque, behind the qibla wall. The roof is made of mud and rodier palm. It is held up by nine inner walls that run from north to south. These walls have pointed arches that go almost up to the roof. This design creates many large rectangular pillars inside the prayer hall. They make it hard to see across the whole space. Small windows on the north and south walls let in only a little natural light. The floor is made of sandy earth.

In the prayer hall, each of the three towers in the qibla wall has a special niche called a mihrab. The imam, or prayer leader, leads prayers from the mihrab in the largest central tower. A small opening in the ceiling of this mihrab leads to a small room above the roof. In the past, someone would repeat the imam's words to people outside. To the right of the mihrab in the central tower is another niche. This is the pulpit, or minbar, where the imam gives his Friday sermon.

The towers in the qibla wall do not have stairs to the roof. Instead, there are two square towers with stairs. One set of stairs is in the southwest corner of the prayer hall. The other set is near the main entrance on the north side. You can only reach these stairs from outside the mosque. Small openings in the roof have removable clay bowls on top. When these are taken off, hot air can escape, helping to cool the inside.

The inner courtyard is to the west of the prayer hall. It measures about 20 by 46 meters (66 by 151 feet). It is surrounded on three sides by covered walkways called galleries. The walls of these galleries facing the courtyard have arched openings. The western gallery is set aside for women.

The mosque is regularly maintained. But since it was rebuilt in 1907, only small changes have been made to its design. For example, the mihrab tower originally had two large openings instead of one central niche. Also, the mosque used to have fewer toron sticks. Pictures show that two more rows of toron were added to the walls in the early 1990s.

Cultural Importance

The whole community of Djenné helps maintain the mosque. They do this through a special yearly festival. This event includes music and food. But its main goal is to fix any damage to the mosque from the past year. This damage is mostly from rain and changes in temperature.

In the days before the festival, plaster is prepared in large pits. It takes several days for the plaster to be ready. It needs to be stirred often, which young boys usually do while playing in the mixture. During the festival, men climb onto the mosque's built-in scaffolding and palm wood ladders. They spread the new plaster over the mosque's walls.

Another group of men carries the plaster from the pits to the workers on the mosque. A race is held at the start of the festival to see who can deliver the first plaster. Women and girls carry water to the pits before the festival. They also bring water to the workers on the mosque during the event. Members of Djenné's masons guild guide the work. Older community members, who have done this many times, sit in a special place in the market square and watch.

In 1930, a copy of the Djenné Mosque was built in Fréjus, a town in southern France. This copy, called the Missiri mosque, was made of cement. It was painted red to look like the original mosque's color. It was meant to be a mosque for the Tirailleurs sénégalais. These were West African soldiers in the French Army who were stationed there in the winter.

The original mosque was once a very important center for Islamic learning in Africa. This was during the Middle Ages. Thousands of students came to Djenné to study the Quran in its schools. The historic parts of Djenné, including the Great Mosque, became a World Heritage Site in 1988. While some mosques are older, the Great Mosque is a major symbol of Djenné and the country of Mali.

3D Documentation

In 2005, the Djenné Mosque was documented in 3D using laser-scanning. This was part of the Zamani Project. This project aims to create 3D records of cultural heritage sites for future generations.

See also

In Spanish: Gran Mezquita de Djenné para niños

In Spanish: Gran Mezquita de Djenné para niños

- Lists of mosques

- List of mosques in Africa

- List of mosques in Egypt

- African Architecture

- Islamic architecture

- Islam in Mali

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |