Britannic facts for kids

His Majesty's Hospital Ship (HMHS) Britannic

|

|

Quick facts for kids History |

|

|---|---|

| Name | HMHS Britannic |

| Owner | |

| Operator | |

| Port of registry | Liverpool, United Kingdom |

| Ordered | 1911 |

| Builder | Harland and Wolff, Belfast |

| Yard number | 433 |

| Laid down | 30 November 1911 |

| Launched | 26 February 1914 |

| Completed | 12 December 1915 |

| In service | 23 December 1915 |

| Out of service | 21 November 1916 |

| Fate | Sank after striking a mine set by SM U-73 on 21 November 1916 near Kea in the Aegean Sea 37°42′05″N 24°17′02″E / 37.70139°N 24.28389°E |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Olympic-class ocean liner |

| Tonnage | 48,158 gross register tons |

| Displacement | 53,200 tons |

| Length | 882 ft 9 in (269.1 m) overall |

| Beam | 94 ft (28.7 m) |

| Height | 175 ft (53 m) from the keel to the top of the funnels |

| Draught | 34 ft 7 in (10.5 m) |

| Depth | 64 ft 6 in (19.7 m) |

| Decks | 9 passenger decks |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed |

|

| Capacity | 3,309 |

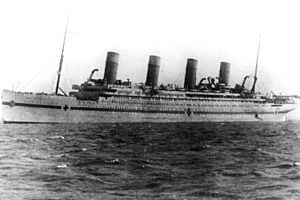

HMHS Britannic was a huge ship built by the White Star Line. She was the third and final ship in the Olympic class class, making her a sister ship to the famous RMS Olympic and RMS Titanic. Britannic was meant to carry passengers across the Atlantic Ocean. However, because of the First World War, she became a hospital ship instead. She served from 1915 until she sank near the Greek island of Kea in November 1916. At that time, she was the largest hospital ship in the world.

Britannic was launched just before the war began. Her design included many safety improvements based on lessons learned from the Titanic's sinking. She was kept at her builders, Harland and Wolff in Belfast, for many months. Then, the government asked to use her as a hospital ship. In 1915 and 1916, she carried wounded soldiers between the United Kingdom and the Dardanelles.

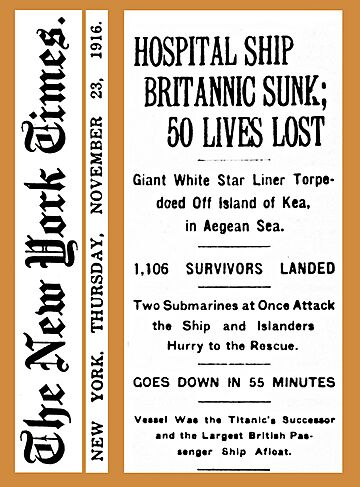

On the morning of November 21, 1916, Britannic hit a naval mine placed by the German Navy. She sank in just 55 minutes, and 30 people lost their lives. There were 1,066 people on board, and 1,036 survivors were rescued. Britannic was the largest ship lost during the First World War.

After the war, the White Star Line received the German ship SS Bismarck as payment for the loss of Britannic. This ship was renamed RMS Majestic. The wreck of Britannic was found and explored by Jacques Cousteau in 1975. It is the largest intact passenger ship on the seabed today.

Contents

Ship Design and Changes

The Britannic was similar in size to her sister ships, but her design was updated after the Titanic disaster. With a weight of 48,158 tons, she was bigger inside than her sisters. However, she was not the largest passenger ship at the time; that title belonged to the German ship SS Vaterland.

The Olympic-class ships used a special engine system. Two engines powered the outer propellers, and their leftover steam powered a third propeller in the middle. This allowed the ship to reach a top speed of 23 knots (about 26 miles per hour).

Safety Updates After Titanic

Britannic looked similar to her sister ships. But after the Titanic sank, many important changes were made to the Olympic-class ships. For Britannic, these changes happened before she was even launched.

- Her width was increased to 94 feet (29 m). This allowed for a double hull (an extra layer of protection) around the engine and boiler rooms.

- Six of her 15 watertight walls were made taller, reaching up to B Deck.

- A more powerful engine was added to make up for the wider hull.

- The central watertight areas were made stronger. This meant the ship could stay afloat even if six of its sections filled with water.

Outside, the biggest change was the addition of large, crane-like gantry davits. These were powered by electricity and could launch up to six lifeboats at once. The ship was designed to have eight sets of these davits, but only five were installed before the war. The rest were regular, hand-operated davits.

Extra lifeboats could be stored on the roof of the deckhouse. The gantry davits could even reach lifeboats on the other side of the ship. This design meant all lifeboats could be launched, even if the ship tilted heavily. Britannic carried 48 lifeboats, each able to hold at least 75 people. This meant over 3,600 people could fit in the lifeboats, which was more than the ship's maximum capacity of 3,309.

Ship's Story

Building a Giant

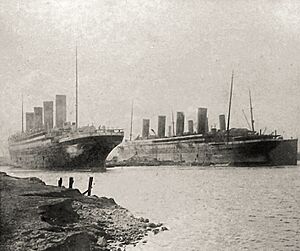

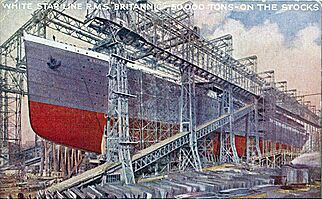

In 1907, the leaders of the White Star Line and the Harland & Wolff shipyard decided to build three huge ocean liners. Their goal was to compete with other big ships by offering unmatched luxury and safety, not just speed. They named these three ships Olympic, Titanic, and Britannic.

Building the Olympic and Titanic started in 1908 and 1909. They were so big that a special structure called the Arrol Gantry had to be built to cover them. This allowed two ships to be built at the same time. The three ships were designed to be 270 meters (886 feet) long and weigh over 45,000 tons. They were planned to travel at about 22 knots, completing a trip across the Atlantic in less than a week.

A Name Change?

Even though the White Star Line and the shipyard always said no, some people believe Britannic was originally going to be named Gigantic. They say the name was changed after the Titanic sank, to avoid comparisons. One piece of evidence is an old poster showing the ship with the name Gigantic. Some newspapers from 1911 also mentioned an order for a ship called Gigantic.

However, the historian for Harland and Wolff, Tom McCluskie, said he never saw any official papers using the name Gigantic. Some changes were made to the ship's order book in 1912, but they only talked about the ship's width, not its name.

Construction Continues

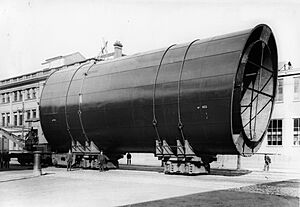

Britannic's construction began on November 30, 1911, at the Harland and Wolff shipyard. She was built in the same spot where the Olympic had been built. This saved the shipyard time and money. The ship was supposed to be ready by early 1914. But because of the safety improvements made after the Titanic disaster, Britannic wasn't launched until February 26, 1914. The launch was filmed, and speeches were given. After launching, the inside of the ship was fitted out. In September, she went into dry dock to have her propellers installed.

In August 1914, before Britannic could start her passenger trips, the First World War began. Shipyards with contracts for the British Navy were given priority for materials. Work on civilian ships like Britannic slowed down. Many large ships were taken by the Navy to carry troops. The Olympic returned to Belfast in November 1914, while work on Britannic continued slowly.

Becoming a Hospital Ship

As the war continued, more ships were needed. In May 1915, Britannic was almost ready. That same month, the Cunard liner RMS Lusitania was sunk by a German submarine.

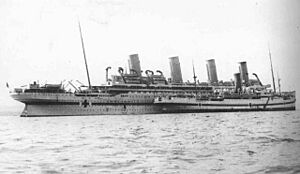

The Navy decided to use large passenger ships to carry troops for the Gallipoli Campaign. But as more soldiers were hurt, there was a great need for large hospital ships. So, on November 13, 1915, Britannic was officially taken over by the Navy to be a hospital ship.

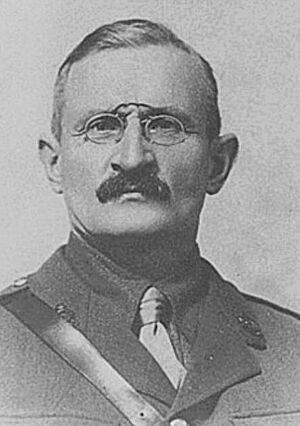

She was painted white with large red crosses and a green stripe. She was renamed HMHS (His Majesty's Hospital Ship) Britannic. Captain Charles Alfred Bartlett was put in charge. Inside, 3,309 beds and several operating rooms were added. The fancy dining rooms became operating rooms, and cabins were used for doctors. Medical equipment was installed by December 12, 1915.

First Journeys

Ready for service on December 12, 1915, Britannic had a medical team of 101 nurses, 336 non-commissioned officers, and 52 officers, plus a crew of 675. On December 23, she left Liverpool for Mudros on the island of Lemnos in the Aegean Sea. Her job was to bring back sick and wounded soldiers. She traveled with other large ships like Mauretania, Aquitania, and her sister ship Olympic. She stopped in Naples to refuel. After her first trip, she spent four weeks as a floating hospital near the Isle of Wight.

Britannic made five successful voyages to the Middle East and back, carrying the sick and wounded.

The Last Voyage

Britannic left Southampton for Lemnos on November 12, 1916. This was her sixth trip to the Mediterranean Sea. She passed Gibraltar and arrived in Naples on November 17 for her usual stop to get coal and water.

A storm kept the ship in Naples until Sunday afternoon. Captain Bartlett decided to leave when the weather briefly improved. The next morning, the storms died down. By the early hours of November 21, Britannic was sailing at full speed into the Kea Channel, between Cape Sounion and the island of Kea.

There were 1,066 people on board: 673 crew members, 315 medical staff, 77 nurses, and the captain.

The Explosion

At 8:12 AM on November 21, 1916, HMHS Britannic was shaken by a huge explosion. She sank 55 minutes later. It was later found that German submarine SM U-73 had placed the mines in the Kea Channel.

In the dining room, doctors and nurses immediately went to their stations. Captain Bartlett and Chief Officer Hume were on the bridge. They quickly realized how serious the situation was. The explosion happened on the starboard (right) side of the ship. It damaged the watertight wall between the first two cargo holds. Water quickly filled the first four watertight sections.

Captain Bartlett ordered the watertight doors to close and sent a distress signal. He also told the crew to get the lifeboats ready. An SOS signal was sent out and received by other ships nearby. However, Britannic could not receive any replies. This was because the explosion had broken the ship's radio antenna wires. So, while she could send messages, she couldn't get any back.

One watertight door failed to close properly, allowing water to flow into another boiler room. Britannic was designed to stay afloat even with her first six watertight sections flooded. This was a safety improvement after the Titanic. However, there were open portholes (windows) along the lower decks. Nurses had opened many of these for fresh air, even though they were told not to. As the ship tilted, water poured in through these open portholes. With more than six sections flooding, Britannic could not stay afloat.

Evacuation and Sinking

Captain Bartlett tried to save the ship. He ordered the ship to move towards the nearby island of Kea, hoping to run it aground. But the ship was tilting heavily, and the steering was damaged. The captain ordered one propeller to spin faster than the other to help steer towards the island.

At the same time, the hospital staff prepared to leave. Bartlett had ordered lifeboats to be ready, but not lowered yet. People grabbed their important belongings. The ship's chaplain even saved his Bible. Patients and nurses gathered on deck.

As the ship tilted more, some crew members launched two lifeboats without waiting for the captain's order. The ship's propellers were still turning, and they sucked these two lifeboats under, destroying them and killing 30 people. Captain Bartlett quickly managed to stop the propellers.

By 8:50 AM, most people had escaped in 35 successfully launched lifeboats. Bartlett thought the sinking had slowed, so he ordered the engines restarted, still hoping to reach the island. But at 9:00 AM, he learned that the flooding had increased. Realizing there was no hope, Bartlett gave the final order to stop the engines and abandon ship. He sounded two long blasts of the whistle. As water reached the bridge, he and his assistant walked off and swam to a lifeboat, where they continued to help with the rescue.

Britannic slowly rolled onto her side, and her funnels collapsed one by one as she sank quickly. By the time her stern (back) was out of the water, her bow (front) had already hit the seabed. Because the ship was longer than the water was deep, the impact caused major damage to the bow. She slipped completely beneath the waves at 9:07 AM, just 55 minutes after the explosion.

When Britannic settled on the seabed, she became the largest ship lost in the First World War and the world's largest sunken passenger ship.

Rescue Efforts

The rescue of Britannics survivors was more successful than the Titanics for a few reasons:

- The water was much warmer (about 20 °C (68 °F) compared to −2 °C (28 °F) for Titanic).

- More lifeboats were available (35 were successfully launched, compared to Titanic's 20).

- Help arrived much faster (less than two hours after the distress call, compared to three and a half hours for Titanic).

Fishermen from Kea were the first to arrive, picking up many survivors. At 10:00 AM, the ship HMS Scourge arrived and rescued 339 people. Another ship, HMS Heroic, arrived earlier and picked up 494 survivors. About 150 people made it to the shore at Korissia, Kea. There, doctors and nurses from Britannic used aprons and pieces of lifebelts to help the injured.

Scourge and Heroic were full, so they left for Piraeus, telling others that more survivors were at Korissia. HMS Foxhound arrived at 11:45 AM and picked up the remaining survivors. Two survivors died on the Heroic and one on a French tugboat. They were buried with military honors. Another person died later in a hospital.

In total, 1,036 out of 1,066 people on board survived the sinking. Thirty people died. Only five bodies were recovered and buried. Others are remembered on memorials. Another 38 people were injured. Survivors were taken to warships and hotels. Many Greek citizens attended the funerals. Most survivors were sent home and arrived in the United Kingdom before Christmas.

What She Would Have Looked Like

The plans for Britannic showed that she was meant to be even more luxurious than her sister ships. She would have competed with other grand liners. She had cabins for passengers in three classes. The White Star Line expected different types of travelers. So, the quality of the Third Class (for immigrants) was lower than on her sisters, but the Second Class was improved. Also, more crew members were planned for Britannic (950) than for Olympic and Titanic (around 860-880).

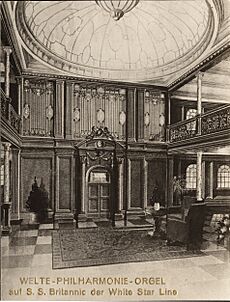

The First Class areas were also made better. Children were becoming a bigger part of the passengers, so a playroom for them was planned on the boat deck. Like her sisters, Britannic would have had a Grand Staircase, but it would have been even more beautiful, with fancy railings and decorations. A pipe organ was also planned. The A Deck was entirely for First Class, with a salon, cafes, a smoking room, and a reading room. A big new feature was individual bathrooms in almost every First Class cabin, which would have been a first for an ocean liner. On Olympic and Titanic, most passengers had to use public bathrooms.

These fancy features were installed but soon removed because the ship became a hospital ship. They were never put back because the ship sank before she could start passenger service. So, these planned features were either canceled, destroyed, or used on other ships like the Olympic or Majestic. Only a large staircase and the children's playroom remained installed.

The Pipe Organ

A special Welte philharmonic organ was meant to be installed on Britannic. But because the war started, the organ never made it from Germany to Belfast. After the war, the shipyard didn't claim it since Britannic had sunk. The White Star Line also didn't want it for Olympic or Majestic. For a long time, people thought the organ was lost.

In 2007, people restoring a Welte organ in a museum in Switzerland found that its main parts were signed "Britanik" by the German builders. A drawing from a company catalog confirmed this was the organ meant for Britannic. It turned out Welte had sold the organ to a private owner instead. Later, it ended up in a concert hall and was eventually bought by the museum in 1969. The museum didn't know its original history until then. The organ still works and is used for performances today.

The Wreck Today

The wreck of HMHS Britannic lies at 37°42′05″N 24°17′02″E / 37.70139°N 24.28389°E in about 400 feet (122 m) of water. It was found on December 3, 1975, by Jacques-Yves Cousteau, a famous ocean explorer. Cousteau filmed his expedition and talked with some Britannic survivors. In 1976, Cousteau and his divers entered the wreck. He believed the ship was sunk by a single torpedo because of the damage he saw.

The huge ship lies on its starboard (right) side, which hides the area where the mine hit. There is a very large hole near the front of the ship. The bow is badly bent but still connected to the rest of the ship. The crew's living areas at the front are in good condition. The cargo holds were found empty.

The machinery at the front and the two cargo cranes are well preserved. The front mast is bent and lies on the seabed near the wreck, with the crow's nest still attached. The ship's bell, thought to be lost, was found in 2019. It had fallen from the mast and now lies on the seabed below the crow's nest. The first funnel was found a few meters from the ship. The other funnels were found scattered in the debris field behind the ship. Pieces of coal are also found near the wreck.

In 1995, Dr. Robert Ballard, who found the wrecks of the Titanic and the German battleship Bismarck, visited the Britannic wreck. He used special sonar equipment. Remote-controlled vehicles took pictures, but they did not go inside the wreck. Ballard found that all the ship's funnels were in surprisingly good condition.

In August 1996, Simon Mills, a maritime historian, bought the wreck. He has written two books about the ship. Since then, many diving teams have explored the wreck, taking photos and videos.

In 2003, an expedition led by Carl Spencer explored the wreck. Divers found that several watertight doors were open. This might have been because the mine hit during a change of shifts, or the explosion might have bent the door frames. Mine anchors were found near the wreck, confirming that Britannic was sunk by a single mine. The damage was made worse by the open portholes and watertight doors.

In 2006, another expedition, filmed by the History Channel, tried to find out why Britannic sank so quickly. Divers explored the wreck, but visibility became very poor, making it dangerous. They couldn't determine the exact cause of the rapid sinking, but they filmed many hours of footage.

Sadly, on May 24, 2009, Carl Spencer died in Greece during his third diving mission to film the Britannic for National Geographic. In 2012, divers installed equipment to study how fast bacteria are eating the ship's iron compared to the Titanic. On September 29, 2019, a British diver, Tim Saville, died during a dive on the Britannic wreck.

Legacy of Britannic

Britannic's career was cut short by the war, and she never carried passengers as planned. Because she had few victims, she is not as famous as her sister ship Titanic. But she became well-known after her wreck was discovered. The White Star Line later used the name again for MV Britannic, which was the last ship to sail under their flag when it retired in 1960.

After the First World War, Germany gave some of its ocean liners to other countries as war payments. The Bismarck was given to the White Star Line and renamed Majestic. She replaced the Britannic. Another ship, the Columbus, was renamed the Homeric.

The last survivor of the Britannic sinking, George Perman, died in 2000. He was a 15-year-old Scout working on the ship when it sank.

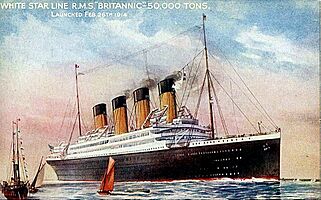

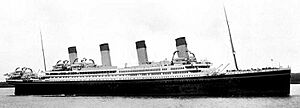

Postcards

- Postcards of Britannic

See also

In Spanish: Britannic para niños

In Spanish: Britannic para niños

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |