Harlequin mistletoe facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Harlequin mistletoe |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Order: | Santalales |

| Family: | Loranthaceae |

| Genus: | Lysiana |

| Species: |

L. exocarpi

|

| Binomial name | |

| Lysiana exocarpi (Behr) Tiegh.

|

|

| Subspecies | |

|

L. exocarpi subsp. exocarpi |

|

|

|

| Occurrence data from AVH | |

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

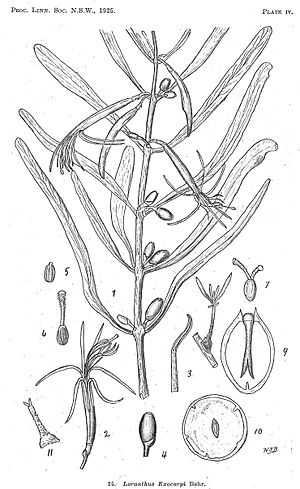

The Lysiana exocarpi, also known as harlequin mistletoe, is a special type of plant that grows on other plants. It's a shrub that is found only in Australia. This plant belongs to the Loranthaceae family, which is a very diverse group of mistletoes with over 900 species around the world. Mistletoes are famous for their unique relationships with other living things.

An early explorer and botanist, Allan Cunningham, wrote about mistletoes in Australia way back in 1817. He described how they grow high up, "Scorning the soil," meaning they don't grow from the ground like most plants.

Contents

What Does Harlequin Mistletoe Look Like?

Harlequin mistletoe is a shrub that can spread out. It doesn't have any hairs on its surface. It also doesn't have roots that spread out on the ground.

Leaves, Flowers, and Fruit

Its leaves can be flat or narrow, like a line. They are usually 3 to 15 centimeters (about 1 to 6 inches) long and 1 to 10 millimeters wide. The tip of the leaf is often rounded. The veins on the leaves are hard to see.

The flowers usually grow in groups of two. They are often bright red, but can sometimes be yellow. They might also have green or black tips. The flowers are quite long, about 2.5 to 5 centimeters (1 to 2 inches).

After the flowers, the plant produces fruit. These fruits are shaped like an oval or egg. They are about 6 to 10 millimeters long and can be red or black.

Different Types of Harlequin Mistletoe

There are two main types, or subspecies, of Lysiana exocarpi:

Lysiana exocarpi subsp. exocarpi

This type has leaves that are wider, usually 3 to 10 millimeters wide. They can be thick or leathery when they are fully grown. This plant often spreads out or hangs down. It usually grows on trees like Acacia, Alectryon, Amyema, Cassia, Casuarinaceae trees, Eremophila, Exocarpos, and even some trees that are not native to Australia. You can find it in the western parts of Australia, starting from the Moree area.

Lysiana exocarpi subsp. tenuis

This type has very narrow leaves, only 1 to 3 millimeters wide. They are not round but can be a bit flat. This plant usually hangs down. It grows in open woodlands and forests, often on Casuarinaceae trees. You can find it in Queensland and New South Wales, from the Darling Downs area down to the Hunter Valley.

Where Does Harlequin Mistletoe Live?

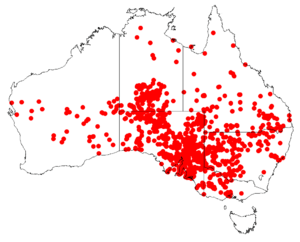

Harlequin mistletoe lives in many different places across Australia. It can be found in dry areas and also in places with more moderate weather. It grows in open woodlands and forests.

You can see L. exocarpi in all mainland Australian states. It grows on many different host plants, but often on other mistletoes from the Loranthaceae family.

The subspecies L. exocarpi subsp. exocarpi is found across arid and temperate Australia. It grows on many host trees, most often on Acacia, Amyema, Cassia, Casuarinaceae, Eremophila, Exocarpos, Alectryon, and non-native trees.

The subspecies L. exocarpi subsp. tenuis is found in Queensland and New South Wales. It usually grows in open woodlands and forests, mostly on Casuarinaceae trees.

Life Cycle of Harlequin Mistletoe

When it Flowers and Grows

Harlequin mistletoe mostly flowers in the summer. Once the seeds are ready, they usually start to grow within one or two days. Sometimes, it can take longer, up to 50 days, for a seed to sprout.

How it is a Parasite

Mistletoes are called "semi-parasites." This means they have green leaves and can make their own food using sunlight, just like normal plants. However, they get all their water and the nutrients dissolved in that water from a "host" plant.

To do this, the mistletoe grows a special woody organ called a haustoria. This organ acts like the mistletoe's roots. It goes through the bark of the host tree and into the young wood. This is where the host tree moves most of its water.

Sometimes, mistletoe leaves even look very similar to the leaves of the plant they are growing on! This is a type of mimicry.

Interestingly, Lysiana exocarpi can even be a parasite on *other* mistletoes, especially different types of Amyema species.

What Plants Does it Grow On?

In New South Wales, harlequin mistletoe often grows on Eucalyptus and Acacia trees. It can also be found on Flindersia, Pittosporum, and Santalum trees.

Scientists have studied many Australian mistletoes and found that they mostly grow on flowering plants (dicotyledons). They can also grow on a few conifer trees like Araucaria, Callitris, and Pinus.

The most common host trees for mistletoes in Australia are Eucalyptus and Acacia. L. exocarpi has been found on over 100 different types of plants! It can even grow on some non-native trees like Nerium oleander, Citrus trees, Prunus trees (like plums and cherries), Schinus molle, and Oak trees.

Some studies suggest that Australian mistletoes, including L. exocarpi, might prefer certain host plants. For example, in South Australia, L. exocarpi subsp. exocarpi often grows on Alectryon oleifolius and Myoporum platycarpum.

Animals and Harlequin Mistletoe

Mistletoes have many connections with animals. Charles Darwin even used them as examples of how living things adapt over time.

Most mistletoe seeds are spread by animals, especially birds. The fruit of the mistletoe has a single seed inside a sticky layer called viscin. This sticky layer is full of sugar. Birds that eat the fruit often have special ways of eating it. They might swallow the seed whole or squeeze it out of the fruit.

The mistletoebird (Dicaeum hirundinaceum) is very important for spreading mistletoe seeds. Some honeyeater birds also help. When birds wipe their beaks on a branch to get rid of the sticky seed, the seed can stick to the branch and start to grow there.

Many insects also visit mistletoes. These include beetles, flies, bees and wasps, and butterflies and moths.

At least 27 types of Australian butterflies use mistletoes as their host plants. This means their caterpillars eat the mistletoe leaves to grow. Some caterpillars will drop to the ground to turn into a chrysalis, but many stay on the mistletoe plant itself.

When harlequin mistletoe is in full bloom, its flowers are a popular food source for birds that feed on nectar.

Harlequin Mistletoe and People

Bushfood

Aboriginal people have traditionally eaten the fruit of the harlequin mistletoe. They would often swallow the fruit whole so the sticky part wouldn't get stuck to their tongues. The fruit is ripe when it's soft and a little bit see-through. The sticky, sweet pulp around the seed is pleasant to eat, but the seed itself is very sticky and hard to spit out! Birds have the same problem and often wipe their beaks on branches to get rid of the seeds.

The berries of L. exocarpi are especially liked by children. Aboriginal groups have different names for mistletoes, but they often don't have separate names for each specific type. For example, the Walpiri people use the word pawurlirri for two different Lysiana species. The Antakirinja people near Coober Pedy call the berries of L. exocarpi Ngantja.

Medicinal Uses

In Europe, mistletoe leaves and young twigs are used in herbal medicine to help with problems related to blood circulation and breathing. Some extracts from mistletoe are sold as medicines.

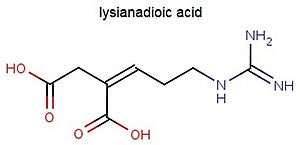

Scientists are also studying mistletoe for other uses. In 2007, researchers in Australia found a new natural substance called lysianadioic acid in a related mistletoe species, Lysiana subfalcata. This substance is interesting because it can stop a certain enzyme (CPB) from working. This is the first time such a substance has been found in a plant.

History of Harlequin Mistletoe

The harlequin mistletoe, L. exocarpi, was first collected in Australia in 1802 by Robert Brown. It was first officially described and named Loranthus exocarpi in 1847 by Hans Hermann Behr. He was a botanist who visited Australia in 1844-45 and studied the plants in the Barossa Range and near the River Murray.

Later, in 1894, a scientist named Philippe Édouard Léon Van Tieghem decided that this plant was different enough to be put into a new group, or genus, which he named Lysiana. The name Lysiana comes from a Greek word meaning "I set free," because he "freed" this plant from the old Loranthus group.

Images for kids

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |