Henry Louis Le Chatelier facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

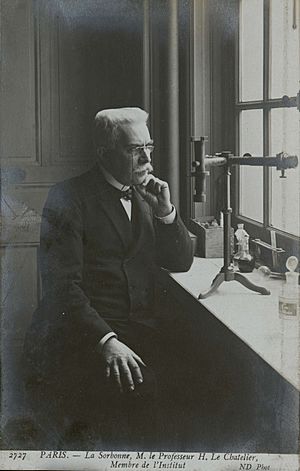

Henry Louis Le Chatelier

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 8 October 1850 |

| Died | 17 September 1936 (aged 85) Miribel-les-Échelles, Isère

|

| Known for | Le Chatelier's principle Thermal flame theory Detonation |

| Parent(s) |

|

| Relatives | Alfred Le Chatelier, brother |

| Awards | ForMemRS (1913) Davy Medal (1916) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Chemistry |

| Institutions | École Polytechnique Sorbonne |

| Influences | Frederick Winslow Taylor |

| Influenced |

|

Henry Louis Le Chatelier (French pronunciation: [ɑ̃ʁi lwi lə ʃɑtlje]; October 8, 1850 – September 17, 1936) was a famous French chemist. He lived in the late 1800s and early 1900s. He is best known for creating something called Le Chatelier's principle. This principle helps scientists and engineers understand how chemical reactions change when conditions like temperature or pressure are altered. It's a very important rule in chemistry!

Contents

Early Life of Henry Le Chatelier

Henry Louis Le Chatelier was born in Paris, France, on October 8, 1850. His father, Louis Le Chatelier, was a skilled engineer. He helped France develop its aluminium industry and improve how iron and steel were made. His father also played a big part in the growth of railways.

Henry's father greatly influenced his son's future career. Henry had one sister and four brothers. His mother raised the children with strict rules. Henry later said that this taught him to respect order and laws throughout his life.

Henry's Education and Military Service

As a child, Le Chatelier went to the Collège Rollin in Paris. When he was 19, he followed his father's path. He enrolled in the École Polytechnique on October 25, 1869. This was a top engineering school.

Like all students at the Polytechnique, Le Chatelier became a second lieutenant in September 1870. He took part in the Siege of Paris. After doing very well in his engineering studies, he joined the École des Mines in Paris in 1871.

Le Chatelier married Geneviève Nicolas, who was a family friend. They had seven children: four girls and three boys. Five of their children later went into scientific fields.

Henry Le Chatelier's Career

Even though Le Chatelier trained as an engineer, he chose to teach chemistry. He was very interested in industrial problems. In 1887, he became the head of general chemistry at the École des Mines in Paris. He also tried to get a teaching job at the École Polytechnique, but he wasn't successful.

Later, Le Chatelier taught at the Collège de France. He then moved to the Sorbonne university. He replaced other famous chemists there.

Teaching Topics

At the Collège de France, Le Chatelier taught many different subjects. These included:

- How things burn (combustion)

- The theory of chemical balance (equilibria)

- How to measure high temperatures

- The properties of metal mixtures (alloys)

- General methods for analyzing chemicals

- The basic rules of chemistry and mechanics

- The properties of silica and its compounds

- Practical uses of chemistry's main ideas

Joining Science Academies

After trying several times, Le Chatelier was finally elected to the Académie des sciences (Academy of Science) in 1907. He was also chosen to be a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in the same year. In 1924, he became an honorary member of the Polish Chemical Society.

Henry Le Chatelier's Scientific Work

In chemistry, Le Chatelier is most famous for his work on Le Chatelier's principle. This principle explains how chemical reactions behave when conditions change. He wrote many papers on this topic between 1884 and 1914. He first shared his findings on chemical balance in 1884 at the Académie des sciences in Paris.

Le Chatelier also did a lot of research on metallurgy. This is the science of metals. He helped start a technical newspaper called La revue de métallurgie (Metallurgy Review).

Work in Industry

A part of Le Chatelier's work was focused on industry. For example, he worked as a consulting engineer for a cement company. This company is now known as Lafarge Cement. His doctoral thesis in 1887 was about how different types of mortars are made.

Le Chatelier's ideas also helped create the oxyacetylene industry. In 1899, he suggested that mixing oxygen and acetylene gases in equal parts could create a flame hotter than 3000 degrees Celsius. This led to the invention of the oxyacetylene torch, which is used for welding and cutting metals.

He also tried to combine nitrogen and hydrogen gases to make ammonia. This was a very difficult experiment. He used high pressure and heat with an iron catalyst. An explosion happened, which almost hurt his assistant. Le Chatelier found out that air in his equipment caused the explosion. Later, another scientist named Fritz Haber succeeded where Le Chatelier and others had failed. Haber even said that Le Chatelier's failed attempt helped speed up his own research. Near the end of his life, Le Chatelier said that letting the discovery of ammonia synthesis slip away was his "greatest blunder."

Understanding Le Chatelier's Principle

Le Chatelier's principle is a very important idea in chemistry. It says that if a chemical system is in balance (equilibrium) and something changes, the system will try to undo that change. It will shift to reduce or get rid of the disturbance. This helps it get back to a stable state.

In simpler words: If you change the amount of a substance, the temperature, or the pressure in a chemical system that is in balance, the system will move in a way that tries to lessen that change.

This rule helps us guess how a chemical reaction will shift.

For example, imagine this reaction:

If you increase the pressure on the gases, the reaction will try to lower the pressure. It does this by making more of the product (ammonia), because two molecules of ammonia take up less space than four molecules of nitrogen and hydrogen.

Here's another example: In making sulfuric acid, one step is:

This reaction releases heat when it goes forward (exothermic). If you add more heat to the system, the reaction will try to absorb that extra heat. It will shift backward, making more of the starting materials (sulfur dioxide and oxygen). This helps to reduce the stress of the added heat. If you lower the temperature, the reaction will shift forward to release more heat.

Henry Le Chatelier's Political Views

It was common for scientists and engineers in Le Chatelier's time to have strong ideas about how industry should work. Le Chatelier published an article about his beliefs on scientific management. This was a theory by Frederick Winslow Taylor about making workplaces more efficient. In 1928, Le Chatelier even wrote a book about Taylorism.

Le Chatelier had conservative political views. In 1934, he wrote about the French forty-hour work week law. However, he stayed away from extreme political groups.

His brother, Alfred Le Chatelier, was a former soldier. He opened a workshop in 1897 that made high-quality ceramics and glassware. Henry Louis Le Chatelier seemed to support his brother's workshop. He even helped with experiments on making porcelain and designed a special thermometer to measure temperatures in the kilns.

Works by Henry Le Chatelier

- Cours de chimie industrielle (Industrial Chemistry Course) (1896; second edition, 1902)

- High Temperature Measurements, translated by G. K. Burgess (1901; second edition, 1902)

- Recherches expérimentales sur la constitution des mortiers hydrauliques (Experimental Research on the Composition of Hydraulic Mortars) (1904; English translation, 1905)

- Leçons sur le carbone (Lessons on Carbon) (1908)

- Introduction à l'étude de la métallurgie (Introduction to the Study of Metallurgy) (1912)

- La silice et les silicates (Silica and Silicates) (1914)

Honours and Awards

Le Chatelier received many honours for his work. He was named a "chevalier" (knight) of the Légion d'honneur in 1887. He then became an "officier" (officer) in 1908, a "commandeur" (Knight Commander) in 1919, and finally a "grand officier" (Knight Grand Officer) in May 1927. He was also accepted into the Academie des Sciences in 1907.

He won the Bessemer Gold Medal from the British Iron and Steel Institute in 1911. He became a Foreign Member of the Royal Society in 1913. In 1916, he was awarded their Davy Medal.

See also

In Spanish: Henry Le Châtelier para niños

In Spanish: Henry Le Châtelier para niños