Henry de Bracton facts for kids

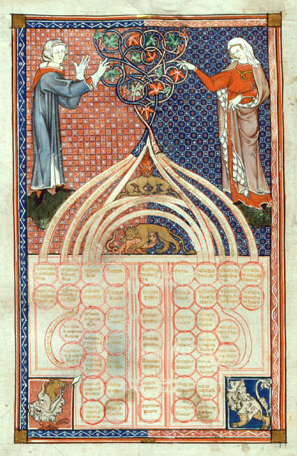

Henry of Bracton, also known as Henry de Bracton (around 1210 – around 1268), was an English church leader and legal expert. He is famous for his writings on law, especially his big book called De legibus et consuetudinibus Angliæ ("On the Laws and Customs of England").

Bracton also had important ideas about mens rea, which means "guilty mind" or "criminal intent." He believed that to prove someone committed a crime, you had to look at both their actions and their intentions. He also wrote about kingship, saying that a ruler should only be called a king if they gained and used power in a lawful way.

In his writings, Bracton clearly explained the laws used in the king's courts. He used ideas from Roman law to do this, bringing new developments from medieval Roman law into English law.

Contents

Life of Henry de Bracton

Henry de Bracton was born around 1210 in Devon, England. He came from a family in either Bratton Fleming or Bratton Clovelly, both villages in Devon. During his life, people knew him as Bratton or Bretton. The name 'Bracton' became common only after he died.

Bracton first worked as a judge in 1245. From 1248 until he died in 1268, he worked steadily as a judge in the southwest counties. These included Somerset, Devon, and Cornwall. He was also part of the coram rege, which was an important advisory council to the king. This council later became known as the King's Court.

He stopped working for the King's Court in 1257. This was just before a big meeting called the Mad Parliament in 1258. It's not known if his retirement was linked to politics. His departure happened around the start of the Second Barons' War in 1264. During this time, Bracton was told to return many old court records, called "plea rolls," that he had. He also had to give back records from earlier judges. Some people think there was political trouble involved.

Because of these events, his main book, De legibus et consuetudinibus Angliæ, was left unfinished. Even so, it is still a very large and important work today. He continued to work as a judge in the southwest until 1267. In his last year, he helped a group of church leaders, nobles, and judges. They were appointed to listen to complaints from people who had lost their lands after siding with Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester.

Bracton was also a church official. In 1259, he became the leader of a church parish in Combe-in-Teignhead, Devon. In 1261, he became the leader of another parish in Bideford. In 1264, he became the archdeacon of Barnstaple and the chancellor of Exeter Cathedral. He was allowed to hold three church positions at once, which showed his special standing.

He was buried in Exeter Cathedral, where an altar bears his name. He had arranged for continuous prayers for his soul, paid for by income from the Manor of Thorverton.

Bracton believed that legal experts were like "priests of the law." He used words from an ancient Roman legal expert named Ulpian. Ulpian said that law is "the good and just art," and those who practice it are "deservedly called priests." Bracton felt this way too, showing his deep respect for the law.

Influences on Bracton

Two important legal experts helped shape Bracton's ideas. The first was Martin de Pateshull. He was a judge who worked for John of England. Bracton greatly admired Pateshull, saying he was always listed first among judges, showing his importance. Pateshull was known for working very hard. He died in 1229.

The second major influence was William Raleigh, who was also from Devon. Raleigh was a judge in 1228. He was seen as a chief judge, even though he wasn't officially called a "justiciar." In 1237, he became the treasurer of Exeter Cathedral. He later became a bishop and died in 1250. Raleigh helped create new legal documents called "writs."

Bracton is thought to have had a notebook with about 2,000 legal cases from Pateshull and Raleigh. He used these cases to write his own book on law. Raleigh also gave land to Bracton. Bracton had been Raleigh's assistant, just as Raleigh had been Pateshull's assistant.

Bracton's Global View of Law

Bracton brought a wider, more international view to the courts of his time. This included ideas from Roman law. This influence had started even earlier, with Ranulf de Glanvill, about 140 years before Bracton.

When the Normans conquered England in 1066, they brought new ideas from Europe. This connected England to the intellectual life of the whole continent. Young English people went to European universities to study. In the 12th and 13th centuries, there was a rebirth of learning in Europe, especially in law. Scholars like Irnerius and Gratian helped revive the study of civil law and church law. Bracton followed this trend in England.

Bracton was also influenced by an early 12th-century lawbook called Leges Edwardi Confessoris. This book supposedly recorded the laws from the time of Edward the Confessor.

After the Norman Conquest, William the Conqueror changed how land was organized. However, many old Anglo-Saxon legal structures stayed the same. Bracton's writings mix old English legal terms with new Norman French terms. This shows how English law was a blend of different cultures at the time.

Bracton's Writings

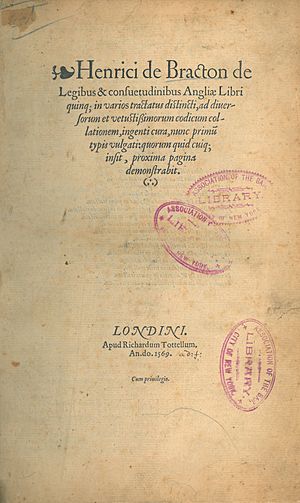

Bracton's most famous written work is De legibus et consuetudinibus Angliæ (The Laws and Customs of England). He started writing it before 1235. Some scholars believe that much of the original text was written by William of Raleigh, and Bracton later updated it. Other scholars think Bracton wrote most of it himself, closer to 1260.

The book was never fully finished. This was likely because of the Second Barons' War. Bracton had access to many "plea rolls," which were official records of court cases. These records were usually not available to the public. He probably had to give them back before he could finish his book. Even so, it is the most complete English law book from the Middle Ages.

Bracton also studied the works of famous Italian legal experts like Azo of Bologna. He knew about important collections of Roman and Church law. He became a supporter of the idea of "Natural Moral Law," which is the idea that some laws are universal and don't change. He believed that certain legal ideas, like "corpus et animus" (body and soul) being needed for legal possession, came from church teachings.

Bracton was the first to comment on the cases he wrote about. He would praise or criticize different court decisions. He called the judges who came before him his "masters." His writing was not like modern law books that compare many case results. Instead, he chose cases and gave a general description of what the law should be. He also included many example "writs" for different situations.

Bracton's book was very important because it was the first time actual court cases were included in English legal writing. Lawyers for the next two centuries learned about case law and legal thinking from his book. This set a new and modern path for English law.

The ability to read actual cases, even if they were old, became very popular. This led directly to the creation of the Year Books. These were yearly collections of court cases. The first known Year Book was published in 1268, the year Bracton died.

Translations

A modern version of Bracton's work was published in 1968 by the Selden Society. It was translated by Samuel E. Thorne. Another important book, Bracton's Note Book, was published in 1887 by Frederic William Maitland.

Church and State in Bracton's Time

In Bracton's time, there were two main legal systems: the "common law" of the king's courts and the "canon law" of the Church. Common law was the general law of the land. It was different from Church law, local customs, and royal orders. New laws were often made through new "writs" (legal commands) created by the King's office, called the Court of Chancery.

Calling Church Leaders to Royal Courts

The relationship between the Church and the King's government was often difficult. Both systems wanted power and control over legal matters. Bracton wrote about "writs" that could be used if a bishop refused to bring a witness to the king's court. This showed the challenges in deciding which court had authority.

For example, if a church official refused to appear in the king's court, the king could order the bishop to make them come. If the bishop still refused, the bishop himself could be summoned to explain why he ignored the king's order. If the bishop continued to refuse, the king could even seize the bishop's lands to force him to cooperate. Bracton believed that even bishops could be arrested for serious wrongs. He wrote that "the sword ought to aid the sword," meaning the king's power should help the Church's power, and vice versa.

Bracton on the King of England

Bracton had strong ideas about the King's power. He wrote: "The king has a superior, namely, God. Also the law by which he was made king." He also said that the king's court, made up of nobles, should guide the king if he acts without law.

Bracton believed that "The king must not be under man but under God and under the law, because the law makes the king." This meant that the king's power came from the law, not just his own will.

Papal Power

Pope Innocent III was a very powerful Pope in the Middle Ages. He made many changes, like saying that church leaders should not earn money from more than one church. Bracton was special because he was allowed to receive income from three churches.

Innocent III believed that all payments to the Church should come before any taxes from the government. He also said that people outside the Church should not interfere in Church matters. He gave the Pope the right to review all important legal cases. These ideas were still causing arguments in Bracton's time.

Bracton, being both a lawyer and a church official, wrote that the Pope had "ordinary jurisdiction over all men in his realm" in spiritual matters. The Pope was a lawmaker and a judge, and his court could enforce his rules.

Contracts and Church Courts

In Bracton's time, contract law started to develop in Church courts. These courts claimed they could enforce promises made under oath. However, Henry II of England wanted these cases to be heard in the king's courts. Henry won this argument. After that, the king's court would stop Church courts from hearing cases about broken promises, unless both people involved were church officials. This was done by issuing a "writ of prohibition."

Sometimes, people would promise not to seek a writ of prohibition, but then change their mind if they didn't like the Church court's decision. Bracton said it was a terrible sin to break such a promise and seek a writ of prohibition.

Church Lands

A common issue in Bracton's time was about land given to the Church, called "frankalmoign." The king's courts often sent "writs of prohibition" to stop Church courts from interfering with the ownership of land, even if it was Church land. Bracton believed that land used for churches was under the Church's authority.

Despite these disagreements, by the end of Henry III of England's rule, the king's courts and church courts generally worked together well.

Modern Ideas of Responsibility

Ideas about who is responsible for harm can be traced from ancient Anglo-Saxon law to Bracton's time. For example, under Alfred the Great, if a person accidentally caused harm with a spear, they were still held responsible. This is similar to the modern idea of "strict liability," where someone is responsible for harm even if they didn't mean to cause it.

Ancient law didn't really discuss "intent" or "mens rea" (guilty mind). But Bracton started to change this. He wrote that a crime like killing, whether accidental or on purpose, should not have the same punishment. He believed that in one case, the full punishment should be given, but in the other, there should be mercy. This was an early step towards the idea that a "guilty mind" is needed for a crime. Bracton emphasized the "animus furendi" (intention to steal) in theft cases.

Other Examples of Law

Sanctuary and Abjuration

If a criminal could reach a church, they were given "sanctuary." This meant the Church was a separate place of safety. Some laws allowed the criminal to stay and be fed by the church for seven days. Bracton suggested 40 days. After that, the local official (reeve) would demand the criminal surrender or leave England forever by the shortest road to a seaport. If they didn't leave the church, they would be starved. If they stayed on the road to the seaport, they were safe. If they left the road, anyone could kill them. However, criminals found with stolen goods or already condemned were not given sanctuary.

Writ of Appeal

Bracton described how a "writ of appeal" should be written for a criminal case. It had to include the year, place, day, and hour of the crime. The person making the appeal had to speak clearly and consistently.

Fairness in Law (Equity)

Bracton wrote about "equity," which means fairness. Around 1258, he said that equity required fair justice and true equality in all situations. He likely got this idea directly from a Roman law book.

Executor of an Estate

In Bracton's time, the person managing a dead person's property (the "executor") could only sue in church courts. This changed later, allowing them to sue in the common law courts.

Murder Fines

Long ago, under Cnut the Great, if an Englishman killed one of the king's men and couldn't prove his innocence, the village where the killing happened had to pay a large fine. This was because the villagers didn't produce the killer. If the village was too poor, the fine was collected from the larger district. This rule was a bit old-fashioned in Bracton's time because trials by "water and iron" (ordeals) had been outlawed in 1215.

Bracton's Lasting Impact

The time of King John of England (1199–1216) was very troubled, leading to the Magna Carta. Henry III of England (1216–1272) became king as a child. Henry de Bracton became one of the greatest judges during Henry III's reign. His legal writings became more important than even the great work of Ranulf de Glanvill.

The Barons' War against Henry III began in 1258. The nobles wanted to reduce the King's power, but they failed. One result of this war was that Bracton couldn't finish his great legal book. New legal actions, like those for trespass, developed during this time. The phrase "Wars are the result of extra-judicial distress" from Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester shows that war was another way for powerful people to get what they wanted, besides the law.

Bracton's work had a huge impact on later legal thinkers. The Constitution of the United States was written by people who knew about Magna Carta and Bracton's ideas. Concepts like "due process" (fair legal treatment) can be traced back to his writings. Bracton believed that the king was subject to God, the law, and his nobles. This idea helped balance the power of later kings.

Bracton's book was popular in his time, and many copies still exist. However, for a while, his influence faded. But the invention of the printing press brought his work back into importance. The edition published in 1569 was very well-made. Bracton's book appeared at an important time during the reign of Queen Elizabeth.

Bracton's ideas about law were slow to be fully accepted in English law. As Parliament gained more power, the legal profession became more focused on practical procedures. Bracton's broad and academic views seemed less practical to them.

Before Bracton, judges rarely looked at old court records. This was because the records were not easily available. Bracton's use of these records led to the idea of publishing summaries of cases. This was a big new idea from Europe. Having access to past decisions, even if they were old, was very interesting to lawyers. This led directly to the Year Books. When many similar cases were decided the same way by different courts, it started to create "precedent," which is the beginning of stare decisis (the idea that courts should follow earlier decisions).

Bracton's writings were read by lawyers in the American colonies in the 1700s. They sometimes used his ideas in their arguments against British rule.

Famous Saying

- Non sub homine, sed sub Deo et lege.

"Not under man but under God and the law."

See also

- Battle of Evesham

- Cnut the Great

- Edward I of England

- Edward the Confessor

- Elizabeth I of England

- Exeter Cathedral

- Henry I of England

- Henry II of England

- Henry III of England

- Isidore of Seville

- Isidorus Hispalensis

- John of England

- Mad Parliament

- Provisions of Oxford

- Quia Emptores

- Richard I of England

- St. Paul's Cathedral

- Second Barons' War

- Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester

- Statute of Marlborough

- Trover

Images for kids

-

Henry de Bracton was appointed to the coram rege, the advisory council of Henry III of England. The photo shows Windsor Castle in Berkshire.

-

Bracton's book was never completed because of the Second Barons' War

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |