History of Easter Island facts for kids

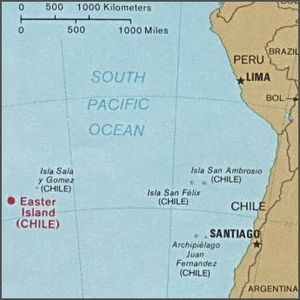

Easter Island, also known as Rapa Nui, is a small island in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. For most of its history, it was one of the most isolated places on Earth. The people who live there, the Rapa Nui, have faced many challenges. They have survived famines, diseases, wars, and even being taken as slaves. Despite these hardships, the island is famous worldwide for its unique culture and giant stone statues.

Contents

- Who Were the First Settlers?

- Did People Come From South America?

- What Was Life Like Before Europeans Arrived?

- Why Did the Statues Fall?

- European Visitors Arrive

- A Time of Great Loss

- A Time of Recovery (1878–1888)

- Joining Chile

- Easter Island in the 20th Century

- Easter Island in the 21st Century

- How Scientists Studied Easter Island

- See also

Who Were the First Settlers?

When Europeans first visited Easter Island, they heard stories about the first people who settled there. These stories say that a chief named Hotu Matu'a arrived on the island. He came in one or two large canoes with his wife and family. Most people believe they were Polynesian people.

Scientists are not exactly sure when the island was first settled. Some studies suggest it was around 300 to 400 CE. Other scientists think it was later, around 700 to 800 CE. A more recent study even suggests it was as late as 1200 CE. This later date might be supported by studies showing that the island's forests started to disappear around the same time.

The Polynesian settlers likely came from the Marquesas Islands to the west. They brought important plants like bananas, taro, sugarcane, and paper mulberry. They also brought chickens and Polynesian rats. The island once had a very advanced and complex society.

Did People Come From South America?

The explorer Thor Heyerdahl thought that some settlers might have come from South America. He noted that Easter Island and South American cultures had some similar traditions. Local legends also tell of two groups of people: the hanau epe (meaning "long-eared" or "stocky" people) and the hanau momoko (meaning "short-eared" or "slim" people). These groups fought, and the hanau epe were almost completely wiped out. This story could mean different things, like a fight between natives and new arrivals, or a conflict between different groups on the island.

However, modern DNA tests of the Rapa Nui people show that they are Polynesian. Skeletons found on the island also suggest that the people living there after 1680 were only of Polynesian origin.

What Was Life Like Before Europeans Arrived?

According to old stories, Easter Island had a clear class system. There was an ariki, or king, who had great power. The most famous part of their culture was making huge stone statues called moai. These statues were part of their ancestral worship, meaning they honored their ancestors. The moai looked very similar and were placed along the coast. This suggests that the island had a strong, unified culture and a central government. Besides the royal family, there were also priests, soldiers, and common people.

Later, for reasons still unknown, military leaders called matatoa took power. They started a new religion focused on a god named Make-make. This was called the Birdman cult (Rapa Nui: tangata manu). Each year, a competition was held. A representative from each clan would swim through shark-filled waters to Motu Nui, a small island nearby. Their goal was to find the first egg laid by a manutara (sooty tern). The first swimmer to return with an egg and climb back up the cliff to Orongo became the "Birdman of the year." This person's clan would then control the island's resources for that year. This tradition was still happening when Europeans first arrived, but Christian missionaries stopped it in the 1860s.

Why Did the Statues Fall?

When Dutch explorers visited in 1722 and Spanish explorers in 1770, they saw many standing statues. But by James Cook's visit in 1774, many statues had fallen over. This "statue-toppling," or huri mo'ai, continued until the 1830s. By 1838, almost all the moai had fallen.

Why did the islanders do this to their ancestors' statues? Theories range from wars between different tribes to people losing faith in their ancestors' ability to protect them. Today, some moai have been restored at places like Anakena and Ahu Tongariki.

European Visitors Arrive

The first European to record visiting Easter Island was the Dutch sailor Jacob Roggeveen. He arrived on Easter Sunday, April 5, 1722. He stayed for a week and estimated there were 2,000 to 3,000 people living there. His group saw the "remarkable, tall, stone figures." They also noted that the island had good soil and climate, and that "all the country was under cultivation."

The islanders were curious about the Dutch and came out to meet them without weapons. Sadly, a shot was fired from an unknown person, leading to a fight where ten or twelve islanders were killed. The Dutch were very upset, especially because one of the dead was a young man they had shown their ship to. The islanders soon returned, not for revenge, but to trade food for the bodies of their fallen. The Dutch left shortly after.

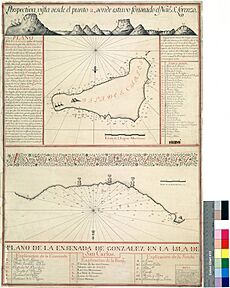

The next visitors were two Spanish ships in November 1770, led by Felipe González de Ahedo. They spent five days exploring the coast. They named the island Isla de San Carlos and claimed it for the King of Spain.

Four years later, in March 1774, the British explorer James Cook visited. Cook was too sick to explore much himself. His crew reported that many statues had fallen. Cook's botanist described the island as "a poor land." Cook estimated about 700 people lived there. He noticed that the islanders now carried weapons, like spears, when approaching visitors.

In 1786, the French explorer Jean François de Galaup La Pérouse visited. He made a detailed map and estimated the population was around 2,000. By the 1800s, Easter Island became a common stop for sealing and whaling ships. Sadly, these visits often included forcing islanders to work on the ships or even outright slave raids.

A Time of Great Loss

A series of terrible events almost wiped out the entire population of Easter Island. Some historians believe the Rapa Nui society destroyed its own environment, leading to wars and a population drop. Others argue that the society was mostly peaceful until Europeans arrived, and that diseases and slave raids caused the catastrophic decline.

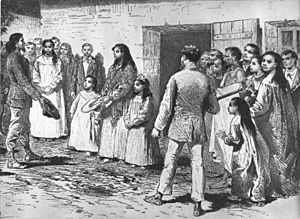

The biggest disaster came in the 1860s when Peruvian slave traders arrived. They were looking for people to sell as laborers in Peru. Easter Island was hit the hardest because it was closest to South America. In December 1862, eight ships arrived. About 1,400 Rapa Nui islanders were kidnapped. Many were sold as servants or forced to work on plantations. They had little food and harsh treatment, and many died from sickness.

News of these slave raids spread, and people in Peru and other countries protested. The Peruvian government finally agreed to free the slaves in late 1863. However, by then, most had died from diseases like tuberculosis, smallpox, and dysentery. Only about a dozen islanders managed to return. But they brought smallpox with them, which caused a terrible epidemic. This reduced the island's population so much that some of the dead could not even be buried.

In January 1864, the first Christian missionary, Eugène Eyraud, arrived. He reported seeing the mysterious rongo-rongo tablets, which had a unique writing system. Many Rapa Nui people became Roman Catholic after Eyraud returned in 1866 with another priest. Eyraud himself caught tuberculosis during the 1867 epidemic. This disease killed a quarter of the remaining 1,200 islanders, leaving only 930 Rapa Nui. Among the dead was the last ariki mau, the 13-year-old Manu Rangi. Eyraud died in 1868, by which time most of the Rapa Nui had become Catholic.

The Influence of Dutrou-Bornier

A French officer named Jean-Baptiste Dutrou-Bornier arrived on Easter Island in 1868. He had a huge impact on the island. Dutrou-Bornier wanted to turn the island into a sheep ranch. He bought almost all the land, except for the missionaries' area around Hanga Roa. He even married a Rapa Nui woman named Koreto and tried to make her Queen.

Dutrou-Bornier moved hundreds of Rapa Nui people to Tahiti to work for his business partners. In 1871, the missionaries, who disagreed with Dutrou-Bornier, moved 275 Rapa Nui to other islands. This left only 230 people on Easter Island, mostly older men. Six years later, in 1877, only 111 people were left.

Dutrou-Bornier was murdered in 1876. Even after his death, much of the island remained a ranch controlled by people from outside the island.

A Time of Recovery (1878–1888)

After Dutrou-Bornier's death, Alexander Salmon Jr. arrived on the island in 1878. He was the brother of the Queen of Tahiti. Salmon managed the island for ten years. He continued sheep farming but also encouraged the Rapa Nui to create their traditional artworks, a craft that is still important today. This was a time of peace and recovery for the island. During this period, the Rapa Nui language changed, influenced by Tahitian. Some of the island's myths also changed to include other Polynesian and Christian ideas.

During this time, scientists began to study Easter Island. German and American ships visited in the 1880s to conduct archaeological studies.

Joining Chile

In 1776, a Chilean priest named Juan Ignacio Molina mentioned Easter Island's "monumental statues" in his book about Chile. Later, in 1837, a Chilean ship called the Colo Colo became the first Chilean vessel to visit the island.

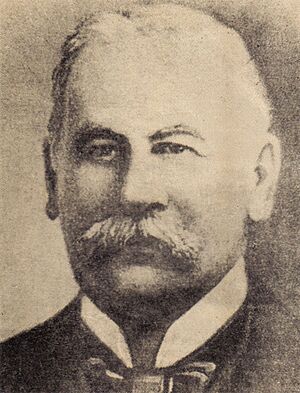

In 1870, Chilean Navy Captain Policarpo Toro visited Easter Island. He was amazed by the Rapa Nui culture and worried about the people's struggles. He thought the island should become part of Chile. At that time, France also considered it one of its Polynesian possessions.

In 1887, Chile took steps to make Easter Island part of its territory. Captain Toro bought land on the island from various owners, including the Salmon brothers. He even used his own money for this purpose. According to Rapa Nui tradition, land could not be sold. However, these purchases were made from non-Rapa Nui individuals who claimed ownership.

By 1892, the Rapa Nui population was extremely low. A census found only 101 Rapa Nui people alive, with only 12 adult men. Their culture was very close to disappearing.

On September 9, 1888, an agreement was signed. The Rapa Nui chief, Atamu Tekena, gave the island's sovereignty to Chile. The Rapa Nui leaders kept their titles and ownership of their lands. They also kept their culture and traditions. The Rapa Nui did not sell their land; they joined Chile as equals.

Joining Chile helped stop foreign slave traders from taking islanders. However, in 1895, a company called Compañía Explotadora de Isla de Pascua took control of the entire island.

The company made rules that limited where the islanders could live and work. They even forced islanders to work for the company. The Chilean Navy later helped the islanders by giving them "safe-conducts" to travel freely across the island. In 1903, an English sheep-farming company bought the island. The Rapa Nui could no longer farm for their own food and had to work on the ranches to buy food.

Easter Island in the 20th Century

In 1914, the Mana Expedition, led by Katherine Routledge, arrived. They spent 17 months studying the island's archaeology and culture. In the same year, German warships gathered off the island before sailing to battles. Another German warship visited and left 48 British and French sailors on the island. These sailors helped the archaeologists with their work.

In 1914, there was an uprising by the Rapa Nui. It was led by Daniel Maria Teave and inspired by the elderly catechist María Angata Veri Veri. They wanted the Chilean government to take action against the company that was causing problems. The Navy blamed the company for "brutal acts" and asked for an investigation.

In 1916, Easter Island became a sub-division of Valparaíso. Archbishop Rafael Edwards Salas visited the island and became a strong voice for the Rapa Nui people's complaints. However, Chile renewed the company's lease. They did give some land to the natives (5 hectares per married couple from 1926). The Navy also established a permanent presence and rules allowing islanders to leave Hanga Roa for fishing or fuel.

Until the 1960s, the Rapa Nui people were mostly confined to Hanga Roa. The rest of the island was rented to the Williamson-Balfour Company for sheep farming. In 1953, the Chilean government ended this contract. The Chilean Navy then managed the island until 1966. That year, the entire island was reopened. The Rapa Nui were given Chilean citizenship, and Spanish became the official language taught in schools. The island also got its own local government, with a governor, mayor, and council. The first mayor, Alfonso Rapu, was sworn in in 1966.

Travel off the island became easier after the Mataveri International Airport was built in 1965. This airport was later extended by NASA in the 1980s to be an emergency landing site for the Space Shuttle. This allowed larger planes to land, bringing more tourists and people from mainland Chile. This increase in visitors has raised concerns about protecting the island's unique Polynesian culture.

After the 1973 Chilean coup d'état when Augusto Pinochet came to power, Easter Island was placed under military rule. Tourism slowed down, and private property was restored. Pinochet visited the island three times. New military facilities and a city hall were built.

In 1975, television arrived on the island. In 1976, the Isla de Pascua Province was created. Since 1984, all governors of Easter Island have been Rapanui. In 1979, a law was passed to give individual land titles to regular holders.

Easter Island in the 21st Century

On July 30, 2007, a change to the Chilean constitution gave Easter Island the status of a "special territory" of Chile. This means it has a unique way of being governed.

A total solar eclipse was visible from Easter Island on July 11, 2010. This was the first time in over 1,300 years that a total solar eclipse could be seen from the island.

Indigenous Rights Movement

Starting in August 2010, members of the Hitorangi clan, an indigenous group, occupied the Hangaroa Eco Village and Spa hotel. They claimed the hotel land was illegally taken from their ancestors by the Pinochet government in the 1990s. In December 2010, Chilean police tried to remove them, and at least 25 people were injured.

In January 2011, a UN expert on Indigenous People, James Anaya, expressed concern about how the Chilean government was treating the Rapa Nui. He urged Chile to talk with the Rapa Nui people to solve the problems. The incident ended in February 2011, when police removed the last occupiers.

Since gaining Chilean citizenship in 1966, the Rapa Nui have worked to bring back their ancient culture. However, land disputes continue to cause tension. Some Rapa Nui people are against private property and prefer traditional communal ownership.

On March 26, 2015, a local group called the Rapa Nui Parliament took control of large parts of the island. They removed park rangers in a peaceful action. Their main goal is to gain independence from Chile. This situation is still ongoing.

How Scientists Studied Easter Island

Easter Island's long isolation ended in 1722 when Dutch explorer Jacob Roggeveen discovered it. He named it for Easter Sunday. The Dutch were amazed by the large statues, which they thought were made of clay.

A Spanish Captain, Don Felipe Gonzales, landed in 1770 and claimed the island for Spain. Captain James Cook stopped briefly in 1774. A French admiral, La Perouse, spent 11 hours on the island in 1786. These early visitors did not stay long. They were looking for water, wood, and food, but the island had little of these. They also noted the lack of safe places to anchor ships. None of these early visitors saw the famous quarry where the statues were carved.

An ethnologist named Alfred Metraux came to Easter Island in 1934-1935. He collected legends, traditions, and myths. His work helped the world learn more about the island's past.

History of Archaeology on Easter Island

Many important archaeological studies have taken place on Easter Island:

- In 1884, Geiseler made a list of archaeological sites.

- In 1889, W. J. Thomson surveyed the island's remains.

- From 1914-1915, Katherine Routledge investigated the statue bases at Rano Raraku. She also explored Motu Nui and found a stone statue.

- From 1934-1935, Henri Lavachery and Alfred Métraux recorded rock carvings (petroglyphs) and studied monuments.

- In 1935, Easter Island was declared a National Park and Historic Monument.

- From 1955-1956, Thor Heyerdahl led a Norwegian expedition. They investigated many monuments to learn about the island's ancient past.

- In 1960, Gonzalo Figueroa and William Mulloy restored statues at Ahu Akivi.

- From 1969-1976, Mulloy and Ayres studied how the statues were carved, moved, and set up. They also worked on restoring many ahu (stone platforms).

- From 1976-1993, Claudio Cristino F., Patricia Vargas C., and others conducted a survey of archaeological sites across the entire island.

- In 1984, a team studied the Orito obsidian quarry. They learned about how obsidian was used and traded.

- In 2011, archaeologists discovered ancient pits filled with red pigment. These pits dated to between 1200 and 1650 CE. This showed that even after the palm trees disappeared, the Rapa Nui continued to produce pigment on a large scale.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Isla de Pascua para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Isla de Pascua para niños

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |