History of Ecuador (1830–1860) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

State of Ecuador (1830–1835)

Estado del Ecuador Republic of Ecuador (1835–1859) República del Ecuador |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1830–1859 | |||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

|

Motto: "Dios, patria y libertad"

|

|||||||||

|

Anthem: Salve, Oh Patria

|

|||||||||

Ecuador from 1830 to 1904

|

|||||||||

| Capital | Quito | ||||||||

| Government | Presidential republic | ||||||||

| President | |||||||||

|

• 1830–1834

|

Juan José Flores | ||||||||

|

• 1834–1839

|

Vicente Rocafuerte | ||||||||

|

• 1839–1845

|

Juan José Flores | ||||||||

| Vice President | |||||||||

|

• 1830–1831

|

José Joaquín de Olmedo | ||||||||

|

• 1831–1835

|

José Modesto Larrea | ||||||||

|

• 1835–1839

|

Juan Bernardo León | ||||||||

|

• 1839–1843

|

Francisco Aguirre | ||||||||

|

• 1843–1845

|

Francisco Marcos | ||||||||

| Legislature | National Congress | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

|

• Established

|

3 May 1830 | ||||||||

|

• March Revolution

|

6 March 1845 | ||||||||

|

• Disestablished

|

31 August 1859 | ||||||||

|

• Battle of Guayaquil

|

22-24 September 1860 | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Today part of | Ecuador Colombia Peru |

||||||||

The history of Ecuador from 1830 to 1860 was a time of big changes. It began when a large country called Gran Colombia broke apart in 1830. This was also the year that two important leaders, Antonio José de Sucre and Simón Bolívar, passed away. Bolívar, who had dreamed of a united South America, was sad to see Gran Colombia fall apart. He famously said, "America is ungovernable."

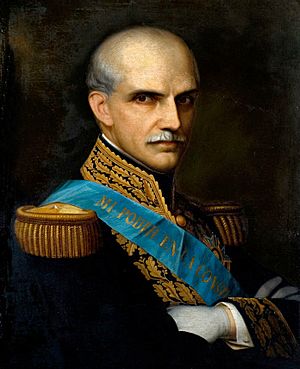

General Juan José Flores became the first President of Ecuador. He ruled from 1830 to 1834. Later, he supported Vicente Rocafuerte to become president, but Flores still held a lot of power in the military. In 1839, Rocafuerte left office, and Flores became president again. However, in 1845, a rebellion called the Marcist Revolution forced him to leave the country.

The next fifteen years were very chaotic. Different groups fought for control of Ecuador. Things got really bad in 1859, which is known as the "Terrible Year." The president at the time, Francisco Robles, faced many groups who were against him. Neighboring Peru, led by President Ramón Castilla, started talking to all the different groups and even blocked Ecuador's ports.

Eventually, the different Ecuadorian groups realized that one of their negotiators, General Guillermo Franco, had betrayed them. They decided to unite against him. In the Battle of Guayaquil, which happened from September 22-24, 1860, Franco was defeated. This battle marked the start of a new, more stable period of conservative government in Ecuador.

Contents

Ecuador's Early Years as a Republic

When Ecuador became independent, life didn't immediately get better for everyone, especially for the local farmers and workers. In some ways, their situation became harder. Spanish officials used to protect them from rich local landowners. But after independence, these protections were gone. The wealthy local people, who had led the fight for independence, gained the most power.

The new country faced a struggle for control among different powerful groups. These included both Ecuadorians and foreigners, and military and civilian leaders. General Juan José Flores, often called the "Founder of the Republic," was Ecuador's first president. He was a foreign military leader, born in Venezuela. He had fought alongside Bolívar in the wars for independence. Bolívar had even made him governor of Ecuador when it was part of Gran Colombia.

Flores came from a simple background but married into a powerful family in Quito. This helped him gain acceptance among the local upper class. However, his main goal seemed to be keeping his own power. The country's money was often spent on military costs, like the wars for independence and a failed attempt to take land from Colombia in 1832. This left little money for other important needs.

In 1833, a group of thinkers started a newspaper called El Quiteño Libre. They used it to speak out against people "stealing from the national treasury." Four of these writers were killed by authorities when Flores was away from the capital, Quito. Even though Flores wasn't directly responsible, people blamed his government. Criticism against him grew stronger.

In 1834, opponents tried to start a rebellion. They wanted Vicente Rocafuerte, a wealthy man from Guayaquil, to become president. This attempt failed. But Flores then made a clever political move: he supported Rocafuerte to become president instead. For the next four years, Flores remained very powerful behind the scenes as the head of the military.

President Rocafuerte's most important achievement was starting a public school system. He believed that Ecuador needed strong leadership to improve. After his term ended in 1839, Rocafuerte became governor of Guayaquil. Flores then became president again in Quito. After four more years, Flores called a meeting to write a new constitution. His opponents called it "the Charter of Slavery" because it allowed him to be elected for another eight-year term.

The Marcist Revolution: A New Beginning

By 1845, many people across the country were unhappy with Flores. An uprising in Guayaquil finally forced him to leave Ecuador. This group of people, who won their fight in March (marzo in Spanish), became known as the marcistas. They were a very mixed group, including thinkers who wanted more freedom, religious leaders, and successful business people from Guayaquil.

On March 6, 1845, the people of Guayaquil rebelled against Flores's government. Generals António Elizalde and Lieutenant Colonel Fernándo Ayarza led them. The people took control of the military barracks and gained support from other soldiers and citizens. Flores surrendered at his farm and agreed to leave power. He also agreed that all his laws and actions would be canceled. This ended fifteen years of foreign influence in Ecuador. Flores received 20,000 pesos for his property and moved to Spain. After he left, the country was led by a group of three people: José Joaquín de Olmedo, Vicente Ramón Roca, and Diego Noboa.

The next fifteen years were some of the most difficult for Ecuador. The marcistas often fought among themselves. They also had to deal with Flores, who tried many times from exile to overthrow the government. The first marcista president was a businessman named Vicente Ramón Roca. He served a full four-year term.

However, the most important person of this time was General José María Urbina. He first took power in 1851 through a coup d'état (a sudden takeover of the government). He was president until 1856 and continued to be a major political force until 1860. During this time, Urbina and his main rival, Gabriel García Moreno, created a strong rivalry between liberals from Guayaquil and conservatives from Quito. This rivalry shaped Ecuadorian politics for many years.

Urbina's liberal ideas included being against the power of the church, and supporting different ethnic groups and regions. In 1852, he accused a group of Jesuit priests of getting involved in politics and sent them away. Urbina also freed the country's slaves just one week after he took power in 1851. Six years later, his friend and successor, General Francisco Robles, finally ended the centuries-old tradition of native peoples having to pay annual tribute. From then on, liberalism became linked with improving the lives of Ecuador's non-white population. Urbina and Robles also favored business owners in Guayaquil over landowners in Quito.

Conflict with Peru and the "Terrible Year"

Ecuador's early years were also marked by a large debt owed to other countries, especially Great Britain. This debt came from the Gran Colombia era. In 1837, President Flores agreed that Ecuador would take on part of this debt. The debt to Britain, called the Deuda inglesa (English debt), was very large. President Francisco Robles tried to pay off this debt by offering to sell some of Ecuador's land to the British creditors.

Relations between Ecuador and Peru had been difficult since 1855. In November 1857, Peru formally claimed that the lands Ecuador wanted to sell to the British actually belonged to Peru. Talks to solve this problem failed. In October 1858, the Peruvian government allowed President Ramón Castilla to go to war with Ecuador if needed. Peru then started blocking Ecuador's ports in November.

1859: The Terrible Year in Ecuador

By 1859, a year known as the "Terrible Year" in Ecuador, the country was in a deep crisis. President Robles faced the Peruvian blockade and moved the capital to Guayaquil. He put General José María Urbina in charge of defending the city. This move was unpopular, and many groups started to oppose Robles.

On May 1, a group of conservatives, including Dr. Gabriel García Moreno, formed a temporary government in Quito. On May 6, another leader, Jerónimo Carrión, tried to form his own government in Cuenca, but it only lasted one day.

General Urbina quickly went to Quito to stop García Moreno's group. The temporary government in Quito was not strong enough and fell in June. García Moreno fled to Peru and asked President Castilla for help. Castilla gave him weapons to fight Robles. Believing he had Peru's support, García Moreno published a message in a Peruvian newspaper in July. He asked Ecuadorians to accept Peru as an ally against Robles, even with the land dispute and blockade.

Soon after, García Moreno met with General Guillermo Franco in Guayaquil. Franco was a powerful military leader. García Moreno suggested they reject Robles's government and hold new elections. Franco agreed, but he also wanted to become president himself. He would later betray his country to get power.

Meanwhile, attempts by other countries to help solve the conflict failed. Peru was playing both sides. On August 31, 1859, Castilla went back on his promise to García Moreno and made a deal with Franco. This ended the blockade of Guayaquil. Later, a secret agreement was signed between Peru and a region of Colombia to take control of Ecuador.

When Robles heard about Franco's deal with Castilla, he rejected it. He moved the capital again, this time to Riobamba, and gave control of the government to Jerónimo Carrión. Robles and Urbina then left the country. Other leaders also declared their own governments in different parts of Ecuador. The country was split into several competing governments.

With Ecuador in such chaos and the Peruvian blockade continuing, Castilla wanted to use the situation to get a good border deal. On September 20, Castilla told Quito that he supported their temporary government. Ten days later, he sailed from Peru with an invasion force. Castilla suggested that the Ecuadorian groups form one government to negotiate an end to the blockade and the land dispute.

October 1859: Talks and Betrayal

Castilla and his forces arrived in Guayaquil on October 4. The next day, he met with Franco on a Peruvian ship. Castilla also sent a message to García Moreno, wanting to meet him. García Moreno traveled to Guayaquil. But when he found out that one of Franco's agents was on the same ship, he became very angry. He told Castilla their alliance was over. Castilla responded that García Moreno was just a "village diplomat" who didn't understand a president's duties.

The Treaty of Mapasingue

Castilla then focused on negotiating only with Franco's government in Guayaquil. After several meetings, they reached a first agreement on November 8, 1859. Castilla ordered his 5,000 troops to land in Ecuador and set up camp near Guayaquil. He did this to make sure Ecuador would keep its promises.

In Loja, one of the other Ecuadorian leaders suggested that all four governments choose someone to negotiate with Castilla. On November 13, Cuenca was forced to recognize Franco's government. This made Franco the leader of both Guayaquil and Cuenca. The next day, Franco and Castilla met again and planned a final peace treaty.

The other Ecuadorian governments finally agreed to let Franco negotiate with Peru, but only on matters that didn't involve giving away land. However, Franco had already been discussing land issues with Castilla. They signed a preliminary agreement about the border on December 4 to end the occupation of Guayaquil and bring peace.

García Moreno soon found out about Franco's unauthorized deal with Castilla. He secretly wrote to the French representative, asking France to make Ecuador a protectorate (a country controlled and protected by France). Luckily for García Moreno, Franco's agreement with Castilla had an important effect: it united the different Ecuadorian governments against Franco, whom they now called "the Traitor."

On January 7, 1860, the Peruvian army prepared to go home. Eighteen days later, on January 25, Castilla and Franco signed the Treaty of 1860. It's better known as the Treaty of Mapasingue, named after the farm where the Peruvian troops stayed. The treaty aimed to solve the border dispute. It said that relations between the two countries would be restored. The treaty also said that an earlier border agreement was canceled. It accepted Peru's claim to certain lands and gave Ecuador two years to prove its ownership of other areas. If Ecuador couldn't provide proof, Peru would gain full rights to those lands. The treaty also canceled all previous agreements between Peru and Ecuador.

1860: A New Government Rises

The very important Battle of Guayaquil took place from September 22-24, 1860. In this battle, García Moreno's forces, led by General Flores, defeated Franco's army. The temporary government in Quito then took power. This marked the beginning of a Conservative era in Ecuadorian history.

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |